At long last, Portlanders will be able to walk up to a food truck this summer and grab a hamburger, taco, hand pie, cup of coffee or other casual fare – years after the food truck revolution invaded other cities across the country.

The presence of a few food trucks downtown (see this comprehensive guide to the fleet) will be a huge step forward for this food-loving city, which struggled over the regulations and made the whole process way more complicated than it needed to be. We should celebrate the fact that the city has finally embraced an idea that will make life here just a little bit better.

But don’t crack open the Champagne too fast.

When food truck operators actually went to get their licenses and open their businesses, they got a couple of unwelcome surprises. Turns out there are still two big regulatory hurdles to get over before we can declare Portland a food truck-friendly place.

First, food truck operators are being required by the city to pay $105 in fees — $30 for a building permit and $75 for an occupancy permit — for every place they park on private property, even though they already have paid for a lease agreement with the property owner. That’s on top of their $500 food truck license and $110 inspection fee. (Night vending is another $200.)

This means that some trucks will have to limit where they can do business, since all those fees add up quickly.

But food trucks are supposed to be mobile, right? That’s the whole point.

“They wrote the ordinance so that it would encourage people to park on private property, basically, instead of roaming around the city and trying to find parking spots, especially in the Old Port and the peninsula,” notes Sarah Sutton, who owns the lobster roll food truck Bite Into Maine and has been trying in vain to get the City Council to take a look at the issue. “It’s really restrictive. And now — I don’t even know how it happened — they’re charging building permits for every spot on private property that they know you’re going to park on.”

This is important because, truck operators say, in order to make their business work at all they must have a place to park on private property. There just are not enough public parking spots available on city streets because of the restrictive limits that were put in place to spare Portland’s restaurants a little competition.

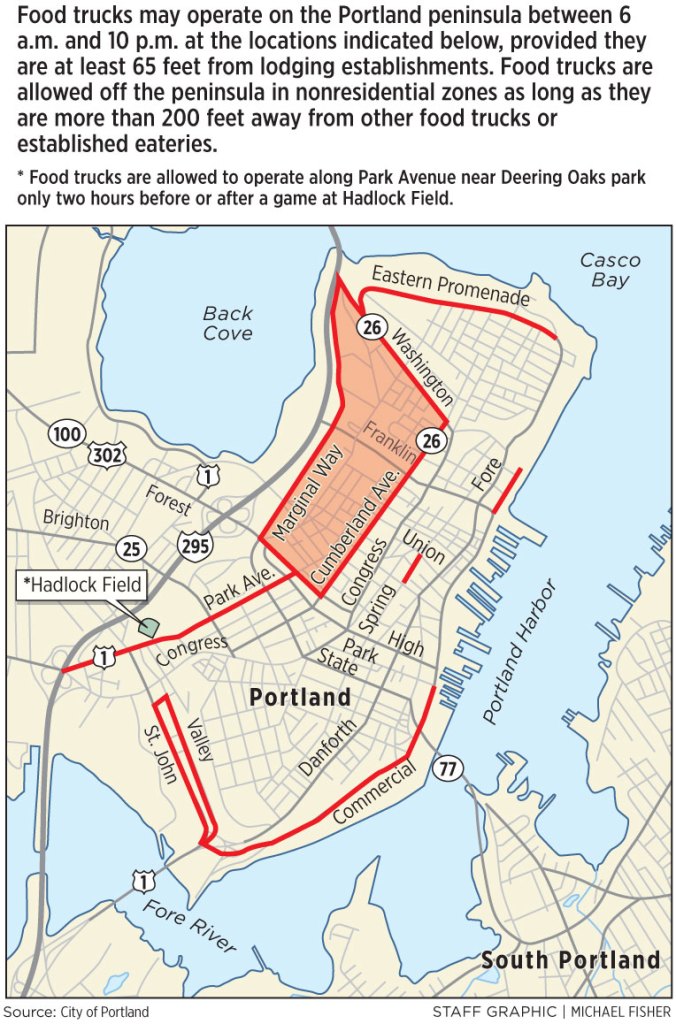

The second issue has to do with clustering. When the ordinance was being developed, food truck operators made it clear they wanted to be able to cluster together in a parking lot, especially for specific events. But when the regulations were published, the rules said food trucks had to stay at least 65 feet from each other on the Portland peninsula, and 200 feet away from each other off-peninsula.

That hasn’t kept some trucks from clustering anyway, at the popular monthly “Flea Bites” gatherings at the Portland Flea-For-All on Kennebec Street, for example. But they are always looking over their shoulders while they’re selling their sandwiches, worried that these popular events will be broken up by the city because of a rule that they didn’t expect to be in the ordinance in the first place.

WHO PAYS THE PRICE?

The rule raises a lot of questions: Who pays the building and occupancy fees when these trucks cluster at an event? The property owner, since there are several trucks involved? Does each truck pay a separate fee, or do they all chip in together and pay once? And do they have to buy a new permit every time they gather, even if it’s a regular weekly or monthly event?

“We had talked to City Council and said we want trucks to be able to cluster, and they had all agreed that was a good idea,” said Ben Berman, owner of Mainely Burgers. “And then the ordinance came out, and it said you can’t. I don’t know why that happened. It was sort of a surprise, but truly we’re not mad at anyone. We’re frustrated that this hasn’t been resolved yet, but happy that some progress has been made.”

The situation is clearly making food truck owners unhappy, but most are limiting their public comments to low-level grumbling, both because they still have to work with the city and are hoping someone in power will take notice and help them fix things.

In referring to the unexpected permit fee, they use phrases like “double dipping” and call it “a little unfair.”

“That does come into play when you move from location to location,” city spokeswoman Nicole Clegg acknowledged. “I will say that these are still kind of new rules and regulations. This is kind of a new concept that we’re applying to existing ordinances. So when issues like the one that you’ve raised come up, it kind of forces us to examine if how we’re applying it is fitting in with the goal of supporting the industry.”

Clegg said the permits are required because the food trucks are being treated like tents and other temporary structures you might set up on your property for a special event.

“We knew when we enacted the rules that there probably were going to be some things that need to get adjusted as we learned more about how the industry operates,” Clegg said. “And this was a good one to point out. We recognize that for someone who’s trying out their business, and trying out a location, that this is a challege for them.”

Sutton said the loose coalition of food truck owners that has formed in Portland has been trying to get the permits and the clustering issue brought up as an immediate concern at City Council for weeks, “and it hasn’t happened yet.” She just found out that Christopher Hall, CEO of the Portland Regional Chamber, will be meeting with the mayor soon to discuss these two issues.

‘FEAR OF THE UNKNOWN’

These glitches could just be considered a learning curve for the city, but they also point to larger concerns that Portland is making it too difficult for food trucks to work here.

“Right now, I think the majority of the rules that are on the books have been influenced by those who are concerned about the impact of the food truck revolution on the standard brick-and-mortar restaurant,” said Carson Lynch, owner of the Gorham Grind truck. “I don’t think that’s necessarily justified. I think it’s fear of the unknown. If you look to other more developed cities, you’ll see that with food culture, there’s a ‘rising tide lifts all boats’ sort of thing. If you’re selling falafel in front of a barbecue place, you’re just going to bring more consumers in general to that neck of the woods, and that’s a good thing. So the code is written based on some fear.”

Jim Chamoff, owner of Gusto’s Italian Food Truck, has been running his business since December and has already found it difficult to work within the city’s rules.

“The biggest issue we’re having quite frankly, is Portland,” he said. “They didn’t make it easy for anybody to do a food truck in Portland. It’s very difficult. We can’t go in the heart of the city where all the foot traffic is, so if you want to find us you have to walk a block or two in a different direction and you have to be looking out for us. We’re not in the center of it. That changes after 10 p.m.; we can pretty much go anywhere. For the late-night crowd, it works pretty well.”

Chamoff tried leasing a spot in a private parking lot, but discovered quickly that he wasn’t going to be doing much business there. So he moved, and everywhere he moves, he has to get a new building permit.

When he has parked on city streets, Chamoff has found it difficult to abide by the parking regulations for food trucks. Moving every couple of hours is not always practical in a big food truck that has to be set up and taken down every time it moves.

“The parking guys are all over us,” Chamoff said. “I mean, they’re just brutal. I’ve literally gotten tickets while on the truck serving food. The bottom line, quite frankly, if they want food trucks in Portland, they’re going to have to change the laws or it’s not going to fly in Portland. Not the way it’s written now. It’s just too restrictive.”

The rules are supposed to be reviewed again in August, a year after they were put in place. Sutton said she hopes that once more people start food truck businesses here, there will be a stronger voice for the movement in the city.

Because if things don’t change, don’t forget: Food trucks are mobile, and they may just motor right out of here.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at mgoad@pressherald.com

Twitter: MeredithGoadONLINE

Send questions/comments to the editors.