LOS ANGELES — Police and politicians across the U.S. are pointing to the example of surveillance video that was used to help identify the Boston Marathon bombing suspects as a reason to get more electronic eyes on their streets.

From Los Angeles to Philadelphia, efforts include trying to gain police access to cameras used to monitor traffic, expanding surveillance networks in some major cities and enabling officers to get regular access to security footage at businesses.

Some in law enforcement, however, acknowledge that their plans may face an age-old obstacle: Americans’ traditional reluctance to give the government more law enforcement powers out of fear that they will live in a society where there is little privacy.

“Look, we don’t want an occupied state. We want to be able to walk the good balance between freedom and security,” Los Angeles police Deputy Chief Michael Downing, who heads the department’s counter-terrorism and special operations bureau.

“If this helps prevent, deter, but also detect and create clues to who did (a crime), I guess the question is can the American public tolerate that type of security,” he said.

The proliferation of cameras — both on street corners and on millions of smartphones — has helped catch lawbreakers, but plans to expand surveillance networks could run up against the millions of dollars it can cost to install and run the networks, experts say.

Whatever Americans’ attitudes or the costs, experts say, the use of cameras is likely to increase in the coming years, whether they are part of an always-on, government-run network or a disparate, disorganized web of citizens’ smartphones and business security systems.

“One of the lessons coming out of Boston is it’s not just going to be cameras operated by the city, but it’s going to be cameras that are in businesses, cameras that citizens use,” said Chuck Wexler, the executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum. “You’ll see the use of cameras will skyrocket.”

Part of the push among law enforcement agencies is for greater integration of surveillance systems. For decades, law enforcement has contacted businesses for video after a crime. An integrated network would make that easier, advocates say.

Since the Boston bombings, police officials have been making the case for such a network.

In Philadelphia, the police commissioner appealed last week to business owners with cameras in public spaces to register them with the department. In Chicago, the mayor wants to expand the city’s already robust network of roughly 22,000 surveillance video.

And in Houston, officials want to add to their 450 cameras through more public and private partnerships. The city already has access to hundreds of additional cameras that monitor the water system, the rail system, freeways and public spaces such as Reliant Stadium, officials said.

“If they have a camera that films an area we’re interested in, then why put up a separate camera?” said Dennis Storemski, director of the mayor’s office of public safety and homeland security. “And we allow them to use ours too.”

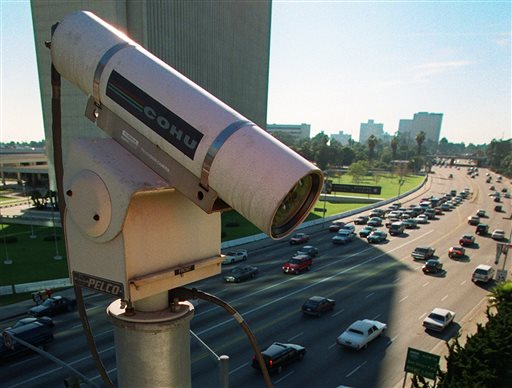

In Los Angeles, police have been working on building up a regional video camera system funded by about $10 million in federal grant dollars over the last several years that would allow their network to be shared with nearby cities at the flip of a switch, Downing said.

That effort is in addition to a recent request by an LA councilman who wants the city to examine allowing police access to cameras used to monitor traffic flow. If that happens, the LAPD’s network of about 700 cameras would grow to more than 1,000.

“First, it’s a deterrent and, second, it’s evidence,” Downing said, adding, “it helps us in the hunt and pursuit.”

Law enforcement experts say police need these augmented systems because the bystander with a smartphone in hand is no substitute for a surveillance camera that is deliberately placed in a heavy crime area.

“The general public is not thinking about the kinds of critical factors in preventing and responding to crimes,” said Brenda Bond, a professor who researches organizational effectiveness of police agencies at Suffolk University in Boston. “My being in a location is happenstance, and what’s the likelihood of me capturing something on video?”

The U.S. lags behind other countries in building up surveillance. One reason is the more than 18,000 state and local law enforcement agencies that each determines its own policy. Another reason is cost: A single high-definition camera can cost about $2,500 — not including the installation, maintenance or monitoring costs.

Law enforcement budgets consist of up to 98 percent personnel costs, “so they don’t necessarily have the funding for new technologies,” Bond said.

There are also questions about their effectiveness. A 2011 Urban Institute study examined surveillance systems in Baltimore, Chicago and Washington, and found that crime decreased in some areas with cameras while it remained unchanged in others. The success or failure often depended on how the system was set up and monitored in each city.

While its deterrent effect remains debated, however, there’s general agreement that the cameras can be useful after a crime to help identify suspects.

Cameras, for instance, allowed police in Britain to quickly identify the attackers behind the deadly 2005 suicide bombings in London. The country has more than 4.3 million surveillance cameras, primarily put in place after the IRA terror attacks.

Dozens are said to sit today around the house of George Orwell, the author of “1984,” a story that foretold of a “Big Brother” society. Privacy advocates in the U.S. are concerned that the networks proposed by officials today could grow to realize Orwell’s dystopic vision.

In recent years, traffic cameras used to catch scofflaw drivers running a red light or speeding have received widespread backlash across the country: An Ohio judge ordered a halt to speed camera citations, Arizona’s Department of Public Safety ceased its program, and there have been efforts to ban such cameras in Iowa.

Amie Stepanovich, director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center’s Domestic Surveillance Project, said the most concerning was an integrated network of cameras that could allow authorities to track people’s movements.

Such a network could be upgraded later with more “invasive” features like facial recognition, Stepanovich said, noting that the Boston surveillance footage was from a private security system at a department store that was not linked to law enforcement.

In many cases, the public may not be aware of the capabilities of the technology or what is being adopted by their local police department and its implications, said Peter Bibring, senior staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California.

Unlike private security systems monitored by businesses or citizens’ smartphones, Bibring said, a government-run network is a very different entity because those watching have “the power to investigate, prosecute and jail people.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.