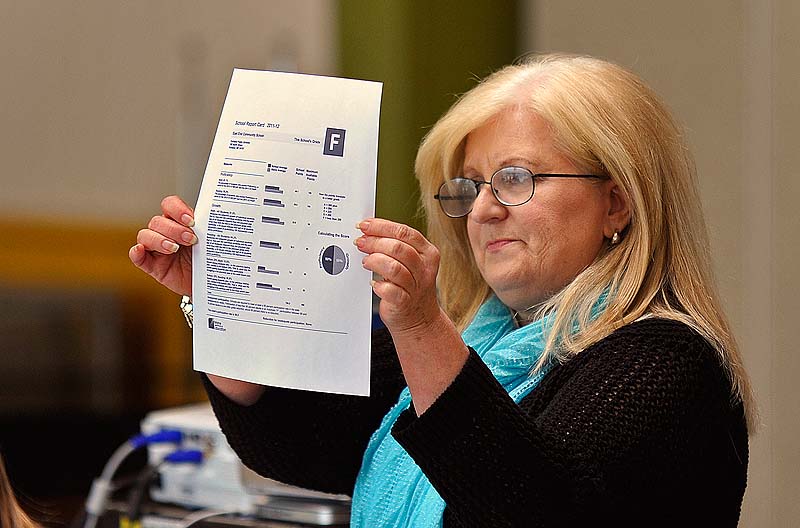

AUGUSTA — The LePage administration unveiled a sweeping statewide grading system for public schools Wednesday that immediately drew sharp criticism from educators, who said it stigmatizes schools in poorer communities.

The A-to-F system, a hallmark of the governor’s education reform efforts, drew support from those who say the grades are a way to let parents gauge how well their children’s schools are performing.

Statewide, the majority of high schools and elementary schools received C grades.

Among elementary schools, only 12 percent got A’s and 13 percent got B’s. Only 8 percent of high schools got A’s and 16 percent got B’s.

At a news conference at the Maine State Library, Gov. Paul LePage said the grades will make schools accountable. He was surrounded by about a dozen Maine students and several international students, who LePage said are enrolled in schools around Bangor and Ellsworth.

“We grade all our children, and now all we’re doing is taking data that’s in the filing cabinets and putting it out so parents, teachers, administrators, anyone and everyone interested in the schools, in a school system in Maine, to see how they’re doing,” LePage said.

“I want the good schools to be rewarded,” he said, “and those that aren’t doing as well, we want to be able to help them.

“It’s for our kids,” he said. “We need to put our kids first. … These kids are our future for our state, country and the world.”

Rob Walker, executive director of the Maine Education Association, criticized the grading system’s methodology. He said the system gives failing grades to schools with the most students in free and reduced-price lunch programs, indicating socioeconomic factors affect a school’s grade.

The MEA, the state’s largest teachers union, noted that in the high schools that got A’s, just 9 percent of the students receive free and reduced-price lunch. In the schools that got F’s, an average of 61 percent get free and reduced-price lunch.

The elementary schools that received F grades have an average of 67 percent of students eligible for free and reduced-price lunch, and the schools that got A’s have an average of 25 percent of students on free and reduced-price lunch.

In the Portland area, Cape Elizabeth, Falmouth and Yarmouth, wealthier communities known for high-performing schools, got A’s for all of their schools.

Walker said research has shown that students who receive free or reduced-price lunch tend to score lower on standardized tests, which are part of the grading system.

He said the grading system will affect Maine communities.

“If you have a system with F’s, you’re going to create a system where businesses, Realtors, parents lose faith in the community because the snapshot is incomplete,” he said. “There are lots of great things going on at these schools that they mentioned, but they got an F.”

The letter-grade plan is the latest education initiative of LePage, who has been sharply critical of public schools. Since he took office in January 2011, the state has opened charter schools and launched a teacher evaluation plan.

His education initiatives, including the letter grades, are closely aligned with reforms pushed by a conservative education reform movement that is sweeping the nation. High-profile leaders include former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, former District of Columbia Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee and the American Legislative Exchange Council.

Craig Wallace, Maine director of StudentsFirst, Rhee’s organization, praised the state’s new system.

“StudentsFirst has consistently supported A-F grading for schools in an effort to provide parents with the information they need to make informed decisions about their child’s education,” Wallace said in a prepared statement.

Although LePage has said the initiative is not partisan, the four legislators who joined him at Wednesday’s event are Republicans, including House Minority Leader Ken Fredette.

Walker criticized the development of the grading system by the state Department of Education and the governor’s staff.

“They invented a system,” he said. “They didn’t involve the communities, they didn’t involve the superintendents or teachers, they invented it just to create a grade. It really reflects back on one speech: The governor says, ‘Hey, let’s give schools a grade.’”

SUMMING UP A SCHOOL

Superintendents for schools that scored low said the announcement that their schools are considered failing was devastating.

“I felt like I had been run over by a train,” said Marcia Gendron, principal at East End Community School in Portland, which got an F. “I actually thought, ‘That can’t be, that’s a mistake.’ ”

East End Community School has been held up by state and federal officials as a success story for how to turn around a struggling school. Since Gendron took over two years ago, the school’s math and reading test scores have improved significantly, and the school has come off the state’s list of persistently low-performing schools.

The fact that it got an F, Gendron said, shows why the totality of a school and its students can’t be summed up in a single letter grade.

Portland’s elementary school grades ranged from A to F. The city’s two largest high schools, Deering and Portland high schools, both got D’s. Casco Bay High School, a smaller, expeditionary learning-based school that opened in 2005, got a B.

“What’s unfortunate is that perception is everything, and perception is not always factual,” Gendron said.

Portland Superintendent Emmanuel Caulk issued a statement that took issue with the grading system’s use of test scores to arrive at letter grades.

“In the Portland Public Schools, we do not assess a student’s year-long performance based on a single test, as we know it is not an accurate reflection of learning,” he said. “Similarly, we do not judge the quality of our schools on a single measure and instead review a range of assessment and data analysis to develop plans for success at all schools.”

He noted that schools were penalized a full letter grade if not enough of their students took state assessment tests, and said Deering High was downgraded to a D because it was a few students short of the 95 percent participation threshold.

“If approximately six additional students had participated in the assessment, Deering would not have been penalized,” Caulk said in the release. “Similarly, Portland High School was penalized one full letter grade for participation in the exam; they were short .6% of the 95% minimum. If approximately two more students had participated in the assessment, Portland High would not have been penalized.”

State officials were quick to acknowledge that a single grade doesn’t capture many elements of a school, but argued that the system’s simplicity is its strength. People understand letter grades, said state Education Commissioner Stephen Bowen, and it’s a sure way to get people talking.

“The phones are going to ring. They’ll ring at the principal’s office, they’ll ring at the superintendent’s office and they’ll ring here,” Bowen said from his office in Augusta. “It’s an attention-getter.”

That’s why the department released the report cards on the day it introduced a “data warehouse” on its website, so parents and others can get detailed data on individual schools. The system has extensive statistics, and can sort and compare among schools, or against state averages.

“We’re hoping people will go in (to the data warehouse) … and ask questions,” said Bowen, whose daughter attends a school that got an A grade.

Critics say such efforts take resources from the public school system, further burden schools and teachers with new requirements, and unfairly allocate public funds.

Bowen and others said they hope to use the school letter grades eventually to identify failing schools and provide state money to help them, perhaps through a $3 million “school accountability” fund proposed in the governor’s state budget. That allocation was rejected last month by the Legislature’s Education Committee, and is now before the budget-writing committee.

Education Department spokesman David Connerty-Marin has described the fund as being similar to the federal School Improvement Grant program, which provides funds to low-performing schools. He said it would use state money to assist schools that don’t qualify for federal assistance under Title I, a program for economically disadvantaged school districts.

Maine’s Democratic leaders were quick to criticize the new grading system. “We are sending a terrible message to parents, students and teachers in our schools,” Assistant House Majority Leader Jeff McCabe of Skowhegan said in a prepared statement from House Democrats.

“The governor should be marketing our state in a positive way, not shaming our communities and our students and driving down our property values,” McCabe said. “His grading system is a cynical and demoralizing effort to advance his so called ‘school choice’ agenda.”

Sen. Rebecca Millett, who represents Cape Elizabeth and South Portland and is a co-chair of the Education Committee, said the system is superficial.

“Standardized test scores don’t reflect the accomplishments of our students in art and music, or business and technical education, or even science,” she said in a news release. “The grades penalize those districts that work to keep their students in school longer to make sure they have the appropriate proficiencies before graduating.”

More than a dozen other states use similar grading systems. In general, the grades are based on standardized test scores in math and English, students’ growth and progress, and the performance and growth of the bottom 25 percent of students. For high schools, graduation rates are a factor.

Education leaders say letter grades are too simplistic for measuring a school’s success.

Connie Brown, executive director of the Maine School Management Association, said that assigning letter grades is at odds with the state’s movement away from assigning letter grades to students. Bowen has strongly supported the move to what’s called standards-based grading.

“I think that when you look at the results, it’s very clear that communities that have the advantages and the resources are the communities that received the A’s, and the communities that are already up against it are receiving F’s,” she said.

QUESTIONS ABOUT FAIRNESS

Several superintendents in southern Maine, even in districts that got all A’s and B’s, said the grades fail to capture the many elements that go into a school community and measure student success.

In Portland, the elementary school grades ranged from A, for Longfellow and Peaks Island, to F, for the East End and Hall schools.

“It’s hard to capture some of the issues that are particular to Portland,” said school board Chairman Jaimey Caron, referring to the city’s large populations of non-English speakers and lower-income students.

“My concern is that (grading schools) leaves too much to the imagination of the parent or the taxpayer. We don’t want people to spend a lot of energy on things that are not real,” Caron said. “I agree that it’s important to characterize the performance of a school, but it has to be a metric that has meaning.”

In Sanford, Superintendent David Theoharides said the high school’s D and the C grades for the elementary schools don’t reflect the “amazing things” the district is doing. He noted that the district recently got new school construction funded, and had one of its teachers honored as Maine Teacher of the Year just a few years ago.

“I see great things happening,” Theoharides said. “I also see a community that struggles economically. Is this a grade that measures the effectiveness of the school or the socioeconomic status of the community?”

Bowen acknowledged that the grades and report cards provide an incomplete picture of what’s happening in a school, but said it’s not possible to create a formula that includes every relevant factor.

Even in districts with high grades, there was criticism of the formula. “It’s brushing your school with a very broad stroke,” said Kennebunk Superintendent Andrew Dolloff, whose schools all got A’s or B’s. “I sympathize with those whose grades aren’t as strong as their communities would like to see.”

There also was concern about the accuracy of the data. Changes were being made to the grades right up until Wednesday’s news conference, after schools got the grades and reviewed the data.

Dolloff said the state told him that Kennebunk High School got a B, but when he checked the data, it should have been an A. The grade was changed after state officials acknowledged that the computer was not programmed to round off numbers, so it read Kennebunk’s 94.9 percent test participation rate as less than 95 percent – and penalized the school a full letter grade.

Several other superintendents called with concerns, said William Hurwitch, director of the state’s educational database.

Only minutes before the 1 p.m. news conference, the Education Department released changes to the database that excluded all of Westbrook’s elementary schools.

Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

Susan McMillan can be contacted at 621-5645 or at:

smcmillan@mainetoday.com

Correction: The caption for a photo accompanying this story was updated at 10:03 a.m., May 2, 2013, to correctly identify Cecelia Joyce, a third-grade teacher at End End Community School in Portland.

Send questions/comments to the editors.