Fairness. Inconsistency. A broken system.

Those are the words the LePage administration has been using to explain why it summoned Maine’s unemployment claims hearing officers to a controversial lunch meeting with the governor at the Blaine House last month.

But state and federal data reviewed by the Maine Sunday Telegram offer little or no evidence to support the administration’s contention that the system is broken, or that unemployment appeals decisions have been skewed against employers.

In fact, the records illustrate that employers consistently win most appeals, and that Maine’s hearing officers perform near the national average.

An analysis of U.S. Department of Labor audits and recent reports by the Maine Department of Labor shows the following:

• Since 2003, quarterly audits mandated by the U.S. Department of Labor show that Maine’s hearing officers have an average appeals performance score of 91 on a scale of 100. That’s about 7 points below the national average but 11 points above the federally required score of 80.

• According to Maine Department of Labor data on cases involving worker misconduct, employers have won an average of 62 percent of appeals filed by workers and decided by hearing officers since 2003.

• Over the past 10 years, employers have won 75 percent of appeals in which workers sought benefits because they claimed they were fired from their jobs.

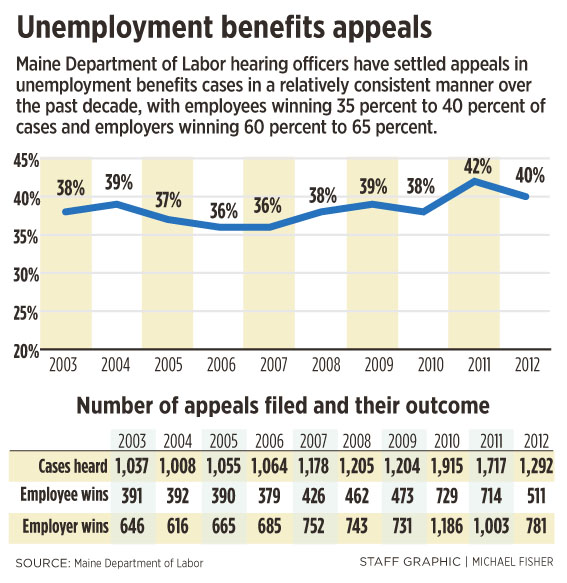

• Hearing officer rulings have been fairly consistent. In the 12,675 cases heard from 2003 through 2012, the number of appeals won by workers accused of misconduct has hovered between 36 percent and 42 percent.

“I haven’t heard concerns about the quality of Maine’s appeals system,” said Brian Langley, the unemployment insurance director for the National Association of State Workforce Agencies, a national organization representing state administrators of unemployment insurance laws.

DIFFERENT VERSIONS OF EVENTS

What happened at the Blaine House luncheon with LePage is a matter of sharp dispute.

The Sun Journal, in an April 11 story, reported that some of the eight to 10 hearing officers, who were not identified because they feared retribution, felt LePage had pressured them to decide more appeals in favor of employers.

That allegation prompted the Maine Unemployment Lawyers Association, whose members represent workers in unemployment cases, to ask the U.S. Department of Labor to investigate what happened at LePage’s meeting.

Apparently in response to that request, two auditors from the federal Employment and Training Administration traveled to Augusta last week. They met twice with Laura Boyett, the director of the state Bureau of Unemployment Compensation, according to state Labor Department visitors records.

The LePage administration offers a different account of events.

It denies that LePage pressured the hearing officers, saying those allegations are politically motivated and based on anonymous media reports.

Spokeswoman Adrienne Bennett said the federal officials came to Maine not to investigate what occurred at the Blaine House meeting but to conduct a routine audit, and to look into LePage’s concerns about “inconsistencies” and the overall quality of the unemployment compensation system.

The administration says it has been contacted by businesses that were concerned about the fairness of the unemployment appeals process, and LePage has cited his own experience as general manager of Marden’s Surplus and Salvage.

Employers have historically been sensitive to appeals that award benefits to workers. The reason: More unemployment claims drive up the rates that employers pay into a trust that funds the unemployment benefit program. The more unemployment claims or appeals rulings that go against an employer, the more that employer pays into the fund.

HOW THE HEARINGS WORK

The hearing officers at the heart of the controversy are the second line of defense in ensuring that Mainers who are entitled to unemployment benefits receive them and that those who are fired for misconduct, or who quit their jobs voluntarily, don’t.

The first line of defense is the intake staff at state unemployment offices, the fact-finders who weigh a claim against the circumstances of an employee’s departure.

The hearing officer, often trained as an attorney, settles disputes between employees and their former employers.

“Essentially, they’re law judges,” said Shari Broder, who was a part-time hearing officer at the state Labor Department from 1996 to 2002. “They hear both sides of a case and make a decision based on the law.”

Despite their legal training, hearing officers earn relatively modest salaries. The most senior officer is currently paid $56,000 a year plus benefits, while junior and part-time officers make $20,000 to $32,000 a year, according to state salary data.

The eight officers together handle an average of about 20 cases a week, making decisions on unemployment benefits that now average about $281 a week.

If a worker or employer disagrees with a hearing officer’s ruling, they can appeal the case to the Unemployment Compensation Commission, a panel whose three members are appointed to six-year terms by the governor and confirmed by the Legislature.

LITTLE EVIDENCE OF SYSTEM PROBLEMS

Jennifer Duddy, the only commissioner appointed by LePage, attended the Blaine House meeting. She has sharply criticized the officers, saying their decisions on what evidence to admit in hearings amount to a “repeated and horrific miscarriage of justice,” according to Linda Rogers-Tomer, the chief hearing officer.

Rogers-Tomer attended LePage’s meeting, met with Duddy again on April 1 and wrote notes on the encounter that the Press Herald obtained under a Freedom of Access Act request to LePage’s office and the Department of Labor.

But there is scant evidence of a miscarriage of justice in either state or federal records.

The Unemployment Compensation Commission, on which Duddy serves, has heard 373 appeals of hearing officer decisions since Dec. 1. Only six of them were remanded for errors relating to evidence issues, according to state Labor Department records.

The federal Employment and Training Administration, which oversees state unemployment programs and sent the two auditors to Maine last week, audits the the appeals process four times a year.

The federal agency evaluates the performance of hearing officers according to 31 different criteria, including perceived bias toward employees or employers, attitude, leading questions and how they handle evidence.

The audit results are expressed on a scale of 1 to 100, with a score of 80 being the federal minimum. Maine has averaged a score of 91 over the past 10 years, below the national average of 98 but above the federal standard.

In the past three years, Maine’s score has increased: from 93.5 in 2010 to 93.75 in 2011 to 95 in 2012.

In addition, federal guidelines require that claims disputes are settled promptly.

Hearing officers have to settle 60 percent of their cases within 30 days or 80 percent within 45 days to conform with federal mandates.

Langley, with the National Association of State Workforce Agencies, said the reason is twofold: First, to ensure that those who qualify for benefits receive them quickly. Second, to ensure that those who shouldn’t qualify can’t collect for too long.

It doesn’t always happen.

“The Great Recession has put a lot of strain on the (unemployment system),” he said, adding that a lot of state systems are under stress because of declining federal funding and the increased claims.

Maine hearing officers did their worst work after the recession hit in 2008 and claims skyrocketed, driving up caseloads and slowing action on appeals.

In 2009, audits show that the performance of Maine’s appeals hearings plummeted to a point where the state was nearly out of compliance with federal mandates. It finished the year 1 point above the minimum acceptable score.

According to a 2010 report by the National Association of State Workforce Agencies, 42 states experienced similar problems with appeals performance.

In the report, state officials explained that a crush of unemployment claims forced the Maine Labor Department to redeploy hearing officers to the front end of the claims system, thus diverting them from a growing caseload of appeals.

Langley, who previously worked for the U.S. Department of Labor and as an auditor in Idaho, described the unemployment system at the time as “a snake eating a rat,” with claims and appeals bunched into one, slowly digesting ball.

He also cautioned that because states have widely varying unemployment systems, national average scores are of limited value in assessing how Maine is doing.

“Those U.S. averages tell you average scores, but not much else about the quality of Maine’s appeals scores,” he said.

Although workloads have swung widely with economic conditions over the past decade, Maine’s unemployment system has produced fairly stable results. State Labor Department records show that employers have consistently prevailed in about 70 percent of the appeals cases heard by hearing officers since 2003.

And for those cases that are taken to the higher level, the Unemployment Insurance Commission, the success rate for employers is closer to 90 percent.

EVIDENCE STILL IN DISPUTE

For the LePage administration, a lack of hard evidence doesn’t indicate that the unemployment system isn’t broken or in need of improvement.

While the federal Department of Labor auditors were here last week, LePage announced that he would be forming a special bipartisan commission soon to investigate the entire unemployment compensation system.

“Numbers in and of themselves don’t tell the entire story,” said Deputy Labor Commissioner Richard Freund. “We’ve heard so often from employers, and the unemployed, and the feedback has been that people have just given up on the system. They don’t want to bother appealing because it ends up being too costly and their sense is that they’re not getting a fair hearing.”

But others are skeptical.

David Webbert, who heads the employment lawyer’s group that asked for a federal investigation of the LePage meeting two weeks ago, said the special commission is being set up to give the administration the results it wants. He also maintains that the governor interfered with the adjudicatory process.

Broder, the former hearing officer, said the allegations were troubling.

“I’m concerned about it, especially as someone who does hearings for other state agencies,” Broder said.

Asked what she’d do if she felt pressure to decide cases one way or another, she said, “I’d probably quit.”

State House Bureau Writer Steve Mistler can be contacted at 620-7016 or at:

smistler@pressherald.com

On Twitter: @stevemistler

Send questions/comments to the editors.