Among the students in Lawrence High School’s Class of 1984, Curt Reid went on to found a solar film company in New Hampshire.

Debbie Wright, now Debbie Theriault, became a personal fitness trainer and owner of a hair replacement salon in Brewer.

Sue Greeley stayed in Albion, where she raised a family.

And Christopher Knight spent 27 years living in complete isolation in a rudimentary shelter in the woods, giving rise to local legends of the North Pond Hermit.

“Nice.” “Quiet.” “Smart.”

These were the words that came up most often from classmates scouring their own memories from 30 years ago for images and impressions of Knight.

They said that before Knight faded into the Maine woods for a quarter-century of solitude, he was already the kind of person who operated at the edges of the school community.

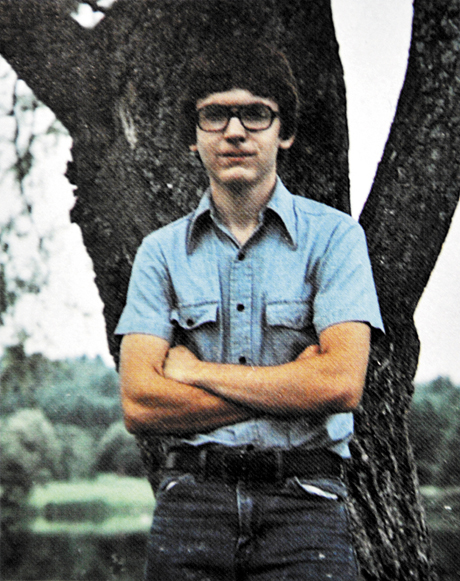

Greeley painted a portrait of a thin, quiet student with thick hair and big glasses who had an interest in computers and was looked down upon by his peers as a nerd.

“I remember him always walking the hallways alone,” she said.

Knight’s quiet, bland personality didn’t attract friends, but it didn’t attract any enemies, either, she said.

“He didn’t do anything to make anybody mad,” she said.

Greeley, who worked in the school’s attendance office, said Knight wasn’t overtly bullied, but that some of the other students would make comments about his awkwardness behind his back.

“You’d hear them say, ‘Oh, look at him. He’s a nerd,’” she said.

If Knight was aware of the criticism, he didn’t seem to be bothered by it, Greeley said.

His happiness, it seemed, lay in something other than the opinions of others.

“Nothing really bothered him,” she said. “He just did his own thing.”

FAINT MEMORIES

Reid said he was shocked when he heard that one of his former classmates had been arrested after apparently having committed more than 1,000 burglaries in the North Pond area of Rome, mostly to take food and basic supplies from camps in the area.

Knight’s current mug shot, in which the corners of the 47-year-old’s mouth are turned down at slightly asymmetrical angles beneath heavily lidded eyes and a bald head, was completely unrecognizable to Reid, who said it bore little resemblance to the quiet classmate he remembers from the early 1980s.

“In my mind, I remembered him with a smile on his face,” Reid said.

Reid said Knight was “a good kid,” pleasant, very smart and quiet, but not abnormally so.

“He was a little socially inept, but nothing out of the ordinary,” Reid said.

When Knight dropped out of sight to go live in the woods, his classmates didn’t notice he was gone. He simply seemed to be one more person who had fallen out of contact with old friends.

“I’ve been to a few class reunions,” Reid said. “I don’t know that his name ever came up.”

Former classmate Christina Hobbs said that in discussions since Knight’s arrest was first reported Tuesday night by the Kennebec Journal, many of her classmates have more questions than memories about Knight.

“Everybody I’ve talked to has been, ‘I didn’t really know that guy,’” she said.

Knight’s newfound fame has been a hot topic of discussion in his hometown of Albion, a tight-knit community of about 2,000 that is served by Lawrence High School in Fairfield. Students from Benton and Clinton also attend the school.

Resident Jeff Lindsay, class of ’83, said Knight’s whole family was quiet, and they all tended to keep to themselves.

“They never had any issues with anybody in town,” he said.

Only Todd Dow, who was in the class behind Knight’s, remembers Knight as talkative, not in class but while riding the school bus alongside people who grew up in his own part of town.

“He talked with those who lived a little closer to him,” Dow said.

Around them, Dow said, Knight was “fairly talkative” and “seemed like a real nice guy.”

Kevin Trask, who lives in Southington, Conn., spent 13 years as a student alongside Knight, beginning at Albion Elementary School, which had a class of about 20 students.

Despite that proximity, he said, Knight didn’t stand out in his memory.

“He just kind of blended in, I guess,” Trask said.

Trask said he never knew Knight to come into conflict with peers or teachers.

Jody Watson, who also attended Albion Elementary with Knight, said she remembered him as no different from all of the other students, other than that he was “a little quieter.” She said she didn’t remember him being involved in sports or other extracurricular activities.

“Chris participated in the same things the rest of us did in the ’70s,” she wrote in an email, “hanging May baskets … square dancing on Fridays with our fourth-grade teacher.”

‘COMPELLED TO HELP’

Knight’s free-loading lifestyle has polarized public opinion between those who want to see him punished heavily for his pilfering and those who see his thievery as relatively benign.

“There are plenty that think he’s no different than other people who steal,” Hobbs said.

Trask, Hobbs and a handful of other classmates, concerned about Knight’s well-being, have begun a Facebook campaign encouraging their old school friends to send donations to Knight at the Kennebec County jail, where he remains held on charges of felony burglary and misdemeanor theft.

Trask said he wants Knight, whose release depends on posting $5,000 in cash as bail, to know that the community he walked away from decades ago cares about his happiness and is willing to give him support.

“Give the guy a chance,” he said. “Maybe he’ll realize, ‘Somebody cares about me.’”

Trask said jail personnel conveyed a message of support from him to Knight.

Hobbs said she plans to send a donation to the jail because she felt “compelled to help.”

“He obviously has some complex problems ahead of him,” she said.

Exactly what role the money will play in Knight’s future is uncertain. The reasons he chose to live his isolated lifestyle haven’t been made public, and it is unclear whether Knight will be able to function in a more traditional setting.

Reid said he saw sadness in Knight’s story, but that his 27-year stay in the woods of central Maine speaks to an urge shared by many.

“I think there’s a part of every male that would say, ‘I would love to go live in the woods and to get off the grid,’” he said.

Trask said he wants to help Knight, even though he’s not sure what kind of future Knight will choose.

“Who knows?” he said. “What if he just walks back into the woods?”

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling can be contacted at 861-9287 or at:

mhhetling@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.