More than a week after the arrest of the elusive North Pond Hermit, it remains unclear what led Christopher Knight to hide in the Maine woods for 27 years and what might become of him.

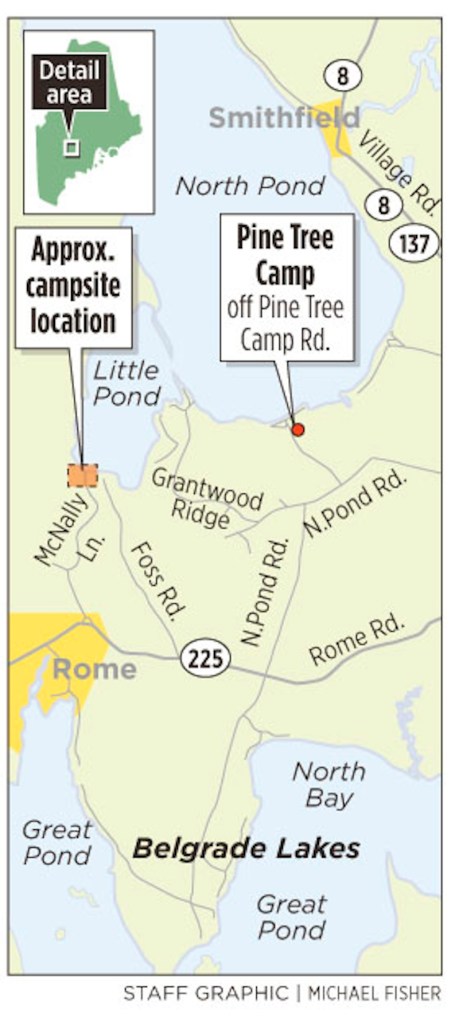

While Knight strived to avoid human contact, he depended on his neighbors in rural Rome and Smithfield, breaking into seasonal camps and cottages to steal food, batteries and other supplies that kept him alive for nearly three decades.

Behavior experts who were interviewed Thursday declined to diagnose Knight’s motives or psychological makeup without examining him, but they offered various assessments and possible explanations for the reclusive, obsessive-compulsive and anti-social behavior described by police, neighbors and others.

“He’s bright, you’ve got to give him credit for that,” said Bill Thornton, a psychology professor at the University of Southern Maine.

“It’s impressive that he was able to go undetected for so long and do the recon to know when people wouldn’t be home,” Thornton said. “If you took one of my students and dropped them in the middle of the woods and told them to survive, I don’t think it would go so well.”

Police say they believe Knight committed more than 1,000 burglaries before finally being caught in the act on April 4, while taking food from the Pine Tree Camp in Rome, one of his favorite targets. They say he was carrying a wad of cash that had grown moldy because he never ventured into a store.

Now 47, Knight was 20 when he went into the woods to live in isolation and deprivation, surviving as a petty thief. At the time, most of his peers were heading out into the world, getting jobs, going to college, forming relationships and starting families.

“It goes against what most people consider typical human behavior,” Thornton said.

Knight has offered few clues to why he left society. He told police that he had a good childhood in Albion, that he has always been interested in hermits, and that he loved the book “Robinson Crusoe,” about a man stranded on an island for decades.

Police say Knight told them he went into the woods after the explosion of the Chernobyl nuclear plant in the Soviet Union in April 1986. But he remembers the event more to recall his date of departure than to explain his motivation.

Behavior experts said painful social awkwardness, emotional trauma or the onset of mental illness, which can occur in the late teens and early 20s, may have prompted Knight to seek a permanent way to avoid human contact.

“It’s possible that he had experiences in childhood and early adulthood that led him to disengage from society,” said John DeLamater, a sociology professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who specializes in intimate relationships and communication.

Thirty years ago, society was less tolerant of, and educated about, challenges that crop up in childhood and adolescence, including sexual identity and orientation issues, learning disabilities and behavioral disorders that might lead a young person to seek isolation, experts said.

After several uncomfortable or undesirable experiences, avoiding human contact might evolve from a possible option to an actual objective, Thornton said.

Knight described behaviors to police that might indicate an obsessive-compulsive disorder or an extraordinary ability to focus that is common among people with autism spectrum disorders, Thornton said.

Knight told police that he stayed in his camp fashioned from brown tarps during the day and ventured out only at night, to avoid being seen.

He spent most days reading books that he stole from neighbors or meditating at his well-camouflaged campsite, sitting on a bucket, looking up at the sky and watching eagles. He walked on roots, rocks and stumps to avoid leaving tracks.

He usually gained weight in the fall so he could eat less during the winter and avoid making treks for food that would leave footprints in the snow. He spent freezing winter days wrapped in layered sleeping bags, rather than start fires that might draw unwanted attention.

“To be that hyperfocused is extremely unusual behavior, and he’s apparently very good at it,” Thornton said. “It’s important to find out what was going on 30 years ago and before that. There had to have been something going on in middle school and even grade school.”

Experts acknowledged that it’s not unusual for people to seek social isolation. Some people have little social interaction other than in the workplace and the grocery store. But extreme examples such as Knight’s are rare, said Dr. Jacqueline Olds, a psychiatrist who teaches at Harvard Medical School.

Olds recalled an Asian student at an American university who was so ashamed of his failing grades that he hid in the rafters of a church for more than seven years, surviving on food from the church’s kitchen, rather than return home and face his family.

Given the extended period that Knight separated himself from humans, including family members in Albion, Olds said she would worry about his state of mind.

“When you’re that out of touch with people for that long, you can get carried away with crazy thinking,” Olds said. “Human interaction is what keeps us all reined in.”

Facing burglary and theft charges, Knight has an uncertain future. His current stay at the Kennebec County jail could be especially difficult for a man who has kept his own schedule, lived outdoors and avoided people for most of his life, Thornton said.

Trying to resume a lifestyle sustained by stealing likely would prove troublesome. At the same time, working a regular job could be difficult for someone who considered fishing and hunting too taxing.

Knight’s options might include living in a halfway house and having occupational training for low-intensity jobs such as stocking store shelves at night, Thornton said.

Experts said they hope he is being evaluated and supported by mental health professionals who will help him transition back into society.

“It’s going to be a big step to get him to confront whatever he’s been trying to avoid for 27 years,” Thornton said.

Kennebec Journal Staff Writers Craig Crosby and Betty Adams contributed to this report.

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at:

kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.