Nicholas Joy did all the right things after he skied off a trail and into the woods Sunday high on Sugarloaf Mountain, said a survival skills instructor.

“My hat’s off to him, for sure,” said Mike Douglas, who owns the Maine Primitive Skills School in Augusta. “If he was doing everything instinctually, he was doing it by the book.”

Joy, 17, of Medford, Mass., got lost as he skied down the mountain Sunday. He and his father had ridden up the Timberline chairlift together shortly after noon and decided to ski down separate trails, then meet at the bottom to head back to Massachusetts. When Nicholas didn’t show up, Robert Joy reported his son was missing.

Eventually, nearly 100 searchers looked for him.

Before he was taken to a hospital Tuesday for an evaluation, Joy told rescuers he built a snow cave to sleep in, found a stream for water, took short walks toward the sound of snowmobiles on Monday, spent another night in the snow cave, and then found and followed snowshoe tracks on Tuesday before he was spotted by a snowmobiler.

Most people in Joy’s situation would have panicked, Douglas said.

“Being lost makes for a frightening proposition,” he said, and people usually begin walking, even in fading daylight and poor visibility, which Joy faced.

That usually gets them more lost, Douglas said, and makes it harder for searchers to find them.

“You have to have the wherewithal to stop and wait for rescue,” he said.

Since hypothermia and dehydration are the biggest dangers for someone who gets lost in the woods, Douglas said, finding or making a shelter and locating a source of water should be the top considerations.

Joy’s snow cave was rudimentary, more like a hollowed-out area in the snow, under a tree, said Cpl. John MacDonald, a spokesman for the Maine Warden Service.

Wardens found it Tuesday after retracing Joy’s steps from where he was picked up by a snowmobiler around 9 a.m. Tuesday.

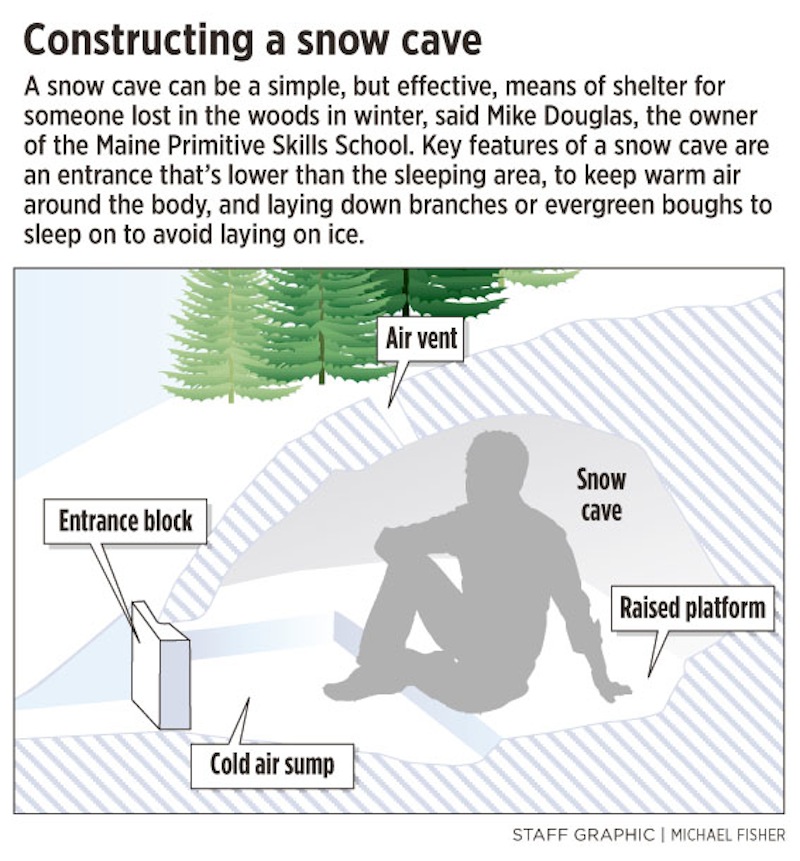

Douglas said the best emergency shelter is a true, covered snow cave, dug into a snow-covered hillside, or what’s called a quinzee, made by piling up snow and then tunneling into it.

Douglas said a snow cave’s entrance should be narrow and below the area where a person will sleep, so the cave will hold the air that’s warmed by the body.

The sleeping area, he said, should be lined with evergreen boughs so the cave’s user doesn’t end up sleeping on snow – which melts from body heat – or ice.

MacDonald said Joy apparently gathered fir boughs to sleep on in his hollowed-out shelter, but he likely would have been quite cold overnight, without anything covering the shelter to retain body heat.

“I’m sure he didn’t sleep much,” he said.

If built right, a snow cave can warm up to the mid-50s, even when the outside temperature is in the single numbers, Douglas said. That’s more than warm enough to ward off hypothermia for someone who’s wearing a parka and ski pants.

“Snow is the most amazing insulator. It’s porous and makes a dead-air space around your body,” he said.

MacDonald said the snow cave that Joy built was right next to Carrabassett Stream. Wardens think Joy followed a small stream down the mountain to where it intersected with Carrabassett Stream, then decided to spend the night there.

Douglas said that suggests Joy was able to “read the terrain” to find a good source of water.

He said Joy’s decision Monday to walk only short distances and then retrace his steps back to the snow cave – what the Warden Service called “directional sampling searches” – was wise.

He stayed connected to where he had built the snow cave – which was relatively near the point where he went off the trail – and didn’t have to try to fashion another sleeping area Monday night.

Joy told wardens he had watched survival shows on television.

Douglas said Joy acted like someone who has been in the woods all of his life.

“He has a respect for the natural world,” Douglas said. “He’s a literate outdoorsman.”

Edward D. Murphy can be contacted at 791-6465 or at: emurphy@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.