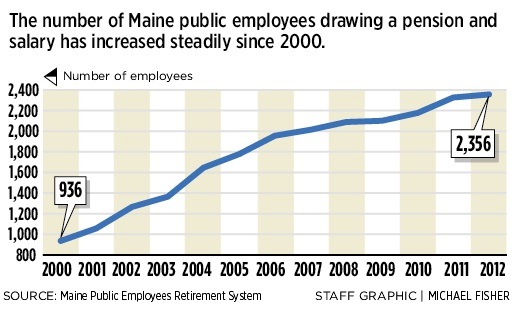

The number of public employees in Maine who are collecting retirement pensions while also earning a salary has doubled over the past decade, a Maine Sunday Telegram analysis shows.

The practice – commonly known as double-dipping – has continued to grow even after the Legislature adopted restrictions in 2011 to discourage it.

At the end of 2012, there were 2,334 state employees who collected both a public pension and a taxpayer-financed salary, according to data provided by the Maine Public Employees Retirement System in response to a Freedom of Access Act request. The total includes state, county and municipal workers and represents about 6 percent of all public employees who received pensions last year.

The number of double-dippers in 2012 increased only slightly from the year before but has jumped by 86 percent in 10 years and by 150 percent in 12 years. In 2002, there were just 1,266 double-dippers in the public retirement system. In 2000, there were 936.

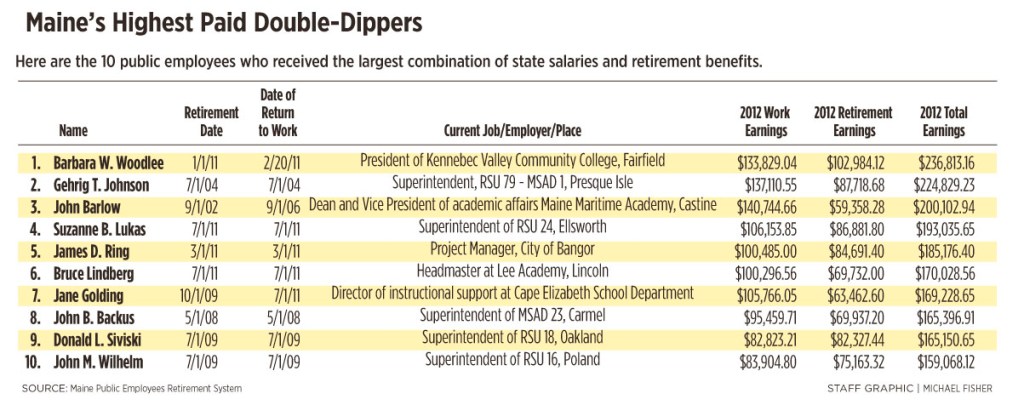

The top 15 employees in 2012 earned more than $150,000 in combined salary and pension benefits and the top three made more than $200,000. On the other end, 17 percent of all employees in the database made less than $1,000 on top of their pension.

To taxpayers, many of whom have lost their own pensions in the private sector, double-dipping is a source of frustration or envy. Defenders of the practice, including some working retirees, counter that there is nothing wrong with the arrangement and that it can actually save the state money. Lawmakers largely agree that the problem lies not with double-dippers but with the pension system itself.

UPDATED NUMBERS SHED NEW LIGHT

An analysis of the state’s latest “return-to-work” data by the Maine Sunday Telegram reveals:

• 224 employees, about 10 percent of double-dippers, retired and then were rehired the same day. A total of 943 employees, about 40 percent, retired and were rehired within two months.

• About half have been working and collecting a pension since before 2009. About one-quarter have been working and collecting a pension since before 2005. A handful have been double-dipping since 1999.

• The average annual retirement earnings among double-dippers was $28,762, although 113 employees made more than $50,000 from their retirement.

• For 2012 earnings, 214 (9 percent) made more than $50,000, while 1,403 (60 percent) made less than $10,000.

The updated numbers shed new light on double-dipping as the Legislature prepares to debate a bill that would undo changes made two years ago in an effort to discourage the practice. As of Sept. 1, 2011, new employees who retire and go back to work can earn only 75 percent of the posted salary and can only work for five years. Based on the 2012 data, the change did little to stop the flow of new double-dippers.

Kathy Morin, a data specialist with the Maine retirement system, said the number has been increasing because people are living longer and working longer, but also because of economic concerns such as high health care costs. The actual number of state retirees who have gone back to work is much higher because the state does not track those who are rehired in the private sector.

Opinions about double-dipping range from Gov. Paul LePage, who in January referred to these workers as “unconscionable” and “absolutely disgusting,” to Maine Education Association President Lois Kilby-Chesley, who said employees are just collecting benefits earned through years of service.

Because state pensions are guaranteed benefits, retirees get the same amount of pension money no matter what is in the fund. However, because the fund has taken a hit in a bad economy, the state and municipalities have been forced to subsidize the retirement fund. That’s where the criticism comes in.

Lewiston school Superintendent Bill Webster, one of the few educators who have publicly opposed double-dipping, said the pension system has become unsustainable. He said the state cannot keep making promises to retirees without the money to back it up.

“Really, the state should cut a check to every retiree and get out of the retirement system,” Webster said. “Except, we don’t have nearly enough money to do it.”

WHO ARE THESE PEOPLE?

Educators make up about 80 percent of all return-to-work employees, but Kilby-Chesley doesn’t see that as a problem.

“In most cases, it’s a veteran teacher with tons of experience who retires and comes back, often part time,” she said. “They don’t get any health benefits and there is no additional retirement contribution. So really, it saves the district money.”

That’s the case with Lance Libby, 64, and his wife, Linda Libby, 65, both of whom are retired teachers who have gone back to work as regular substitutes.

“I could go work in my son’s wood shop and no one would know,” said Lance Libby, who lives in Bowdoin. “But I’m a better teacher than I am a woodworker. And I still like working with kids.”

The Libbys both retired in July of 2006 and went back to work in January 2007. In the years since, the amount of days each has been asked to substitute teach has varied. Last year was a good year: Lance made $11,955 as a regular sub; Linda made $12,617. Their combined pension was a little more than $77,000.

“It hasn’t been about the money for us,” Lance Libby said. “We don’t need it. But there is a need for reliable substitutes, or else we wouldn’t keep getting calls.”

Outrage about double-dippers is directed less at folks like the Libbys and more at people like Suzanne Lukas.

Lukas is a former superintendent of SAD 6 in Buxton. She retired effective July 1, 2011, and then went to work immediately as superintendent of RSU 24 in Ellsworth. In 2012, Lukas made $106,153 in salary and $86,881 in pension, the fourth highest total earnings in the state.

Lukas objects to the term double-dipper. She said she worked hard for that pension and continues to work hard for her salary.

“People say it like it’s a negative thing,” she said. “But we have military retirees who get a pension and come to work at school and no one says anything about that. It’s a retirement plan. That’s all.”

She also said all school districts are equal-opportunity employers.

“They didn’t have to hire me,” she said. “But I was the best person for the job.”

Sandra MacArthur, director of the Maine School Management Association, which represents superintendents, said there are 20 open superintendent positions currently and as many as 12 administrators who have an interim tag. The positions are hard to fill with qualified candidates, she said.

Although educators make up the largest group of double-dippers, there are nearly 300 state employees and a little more than 100 municipal workers whose communities are, or were, part of the state retirement system.

Six employees of the Maine Attorney General’s Office, including William Stokes, the head of the criminal division, are on the list. Two members of LePage’s Cabinet – Finance Commissioner Sawin Millett and Inland Fisheries & Wildlife Commissioner Chandler Woodcock are double-dippers – as is Col. Patrick Fleming, head of the Maine State Police. Two of LePage’s executive department staff members also are retirees who have come back to work.

Among the 295 state employees who collect a pension and salary, some departments are well represented. There are 29 in the Department of Health and Human Services and 24 in the Department of Conservation. Other departments have few. The Department of Marine Resources has two double-dippers; the Department of Environmental Protection has just one.

The Portland School Department, the state’s largest district, has the most double-dippers of any employer, with 63, up from 45 in 2011.

James Ring, a project manager for the City of Bangor, is the only non-educator in the top 10 list of highest earners in 2012. He made $100,485 in salary and $84,691 in pension.

Ring was a longtime municipal employee and retired as city engineer in March 2011. Because of his experience, he was hired back immediately to help oversee the city’s role in the construction of a new arena and convention center. But his contract ends when the new facility is built.

WHY IT’S A PROBLEM

Until 2011, the age at which Maine public employees could retire and begin collecting a pension was 62, or 60 for employees who had at least 10 years of service by 1993. The age has been increased to 65 for new hires in part to help stabilize the pension fund.

The pension amount is based on a formula that takes into account three things: the average of an employee’s three highest years of earnings, the number of the years of creditable service and the employee’s age at retirement.

The Maine State Retirement System pension is classified as a defined benefit, which means retirees collect the same amount each year, sometimes adjusted for cost of living, no matter what happens on Wall Street.

It’s a lot like Social Security benefits, which makes sense because the public employee pension in Maine replaces Social Security. Workers do not pay into nor do they receive Social Security.

In the private sector, most employers have done away with employee pensions and replaced them with individual retirement accounts, such as 401(k)s, which are considered direct-contribution plans.

Workers pay in as much as they choose and their employer often matches up to a certain amount, but the fund fluctuates depending on how the money is invested. Any gains go to the worker but losses are the worker’s responsibility as well.

In pensions, the employer must absorb any market losses. In the Maine retirement system, that’s the state of Maine and local municipalities or school districts. Put another way, it’s taxpayers.

“We’ve made promises that we can’t back up,” said Webster, the Lewiston superintendent.

Luke Martel, a senior policy analyst with the National Conference of State Legislatures, said public pensions are a big concern in many states. Some states, including four last year, have made changes to their system to directly address employees who return to work. But states seem more interested in changing the system. Since 2009, Martel said, 45 states have enacted changes to retirement plans. In 32 states, the retirement age was increased; in 20 states, cost-of-living adjustments were reduced. Six states have made what Martel called fundamental changes to public pensions by phasing out the defined-benefit plan.

Maine lawmakers passed a bill in 2011 that made changes to the double-dipping law in an effort to discourage the practice. It created a restriction that says those who go back to work after retiring can only make 75 percent of the posted salary for that job. It also created a five-year cap.

This session, a bill sponsored by Rep. Peter Johnson, R-Greenville, would reverse those changes for educators.

“I think the original motivation was to cut down the number of superintendents coming back, but the unintended consequence was hurting ed techs or teachers, especially in rural areas,” he said.

Sen. Dawn Hill, D-Cape Neddick, sponsored a similar bill during the second session of the last Legislature but it was not approved.

“I don’t think (double-dipping) is immoral or unethical, it just doesn’t feel right,” she said. “Clearly, restricting pay has not stopped retirees from going back to work.”

Hill said a better tactic might be to stop allowing new hires into the pension system and replace it with a defined-contribution plan. She said that would not be an easy change.

Johnson said he understands the concern about the long-term sustainability of the pension fund, but he said people shouldn’t be upset with double-dippers. Those employees would be paid that money whether they went back to work or not. And those 2,334 employees in 2012 earned a combined $67.1 million, which represents only about 9 percent of the total benefits paid.

“I think we need to figure out how we can stop accepting new people into the retirement system and I think a lot of people want to see that happen,” he said. “But you couldn’t apply it retroactively. These retirees were promised benefits.”

Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.