Opening statements have yet to be made in the trial of Mark Strong Sr., but already the Kennebunk prostitution case is a study in legal maneuvering.

On one side is Daniel Lilley, Strong’s lawyer and one of Maine’s most respected defense attorneys.

On the other is York County Deputy District Attorney Justina McGettigan, who lacks Lilley’s decades of trial experience but is considered a thorough and fearless prosecutor.

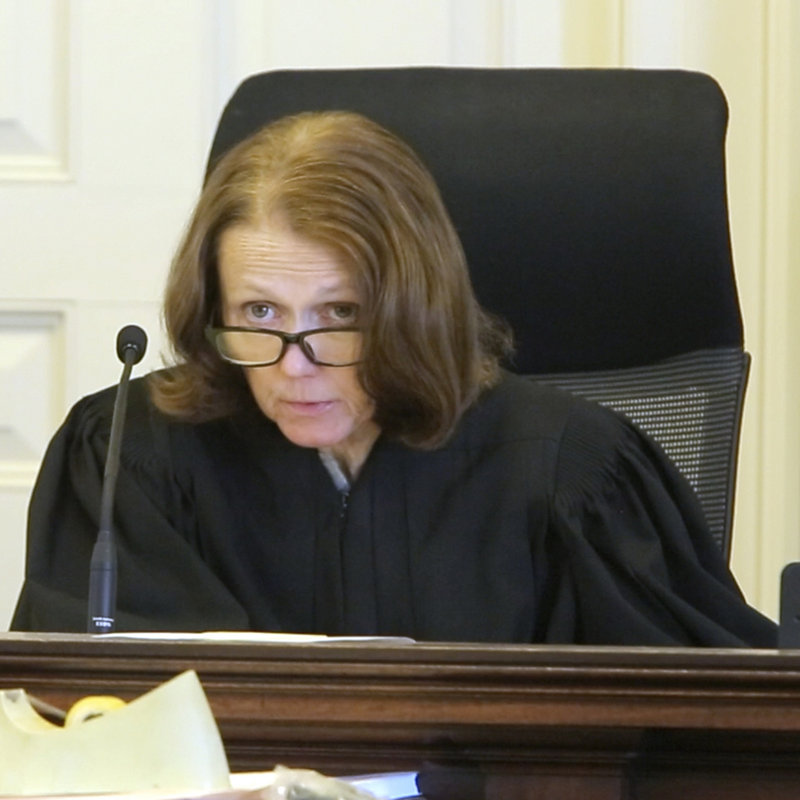

Presiding over it all is Superior Court Justice Nancy Mills, who must steer the high-profile case through what has been a steady stream of legal arguments and media scrutiny.

Since the proceedings started on Jan. 22, there have been numerous stops and starts and, at times, confusion.

Mills has seen one of her decisions overturned by the state’s highest court, which also agreed to hear an appeal of her decision last week to drop most of the 59 charges against Strong.

She dismissed 46 counts of violation of privacy, prompting prosecutors to appeal to the Maine Supreme Judicial Court and ask for the trial to be stopped until a ruling is issued. On Tuesday, the court agreed to hear the appeal.

Earlier in the day, there was momentary confusion in York County Superior Court when Mills dismissed the jury pool after rejecting a motion by Lilley to go ahead with trial on the 13 remaining counts against Strong.

She reversed herself after learning that York County, where she normally doesn’t hear cases, retains jury pools for two months, unlike Cumberland County, where jury pools are retained for only a month.

Has Mills lost control of the trial before it has really begun?

She has done nothing to suggest that, said Jim Burke, a professor at the University of Maine School of Law. On the contrary, he said, Mills is living up to her reputation as a tough, measured judge who believes in a fair process.

“She has to deal with what comes before her, and the attorneys for the two sides are firing everything they can to gain an advantage,” Burke said Tuesday. “Her job is to call balls and strikes.”

Walter McKee, a veteran defense attorney in Augusta who has tried dozens of cases before Mills, called her “the perfect judge” for the Kennebunk prostitution case.

“It’s a thankless case, but she’s the kind of person to take those on,” he said. “Above all, she makes sure everyone gets a fair trial. And she’s certainly not afraid to make a tough decision.”

Leonard Sharon, a defense attorney from Lewiston who also has appeared before Mills many times, agreed.

“When she makes an order, if it’s not followed, you’re going to hear about it,” Sharon said. “I’ve never known her to lose control. Her strength is her ability to control her courtroom.”

Mills has long been accustomed to being in control. She has been a Superior Court justice since 1993, and was chief justice from 2001 to 2004.

Before that, she was a District Court judge and assistant district attorney in Kennebec and Somerset counties. She is a graduate of the UMaine School of Law and was editor of the Maine Law Review.

Her husband, Peter Mills, is the director of the Maine Turnpike Authority and a former state lawmaker and gubernatorial candidate. One sister-in-law is Maine Attorney General Janet Mills.

Nancy Mills’ 20-year history as a Superior Court justice is varied. It’s hard to derive specific tendencies from cases she presided over, although Mills has imposed some stiff sentences.

In February 2010, she sentenced Leo Rose Hylton to 90 years in prison, with 40 years suspended, for attempted murder, robbery and burglary.

During the sentencing, Mills said, “There’s only a few defendants who come into court where a judge truly feels that she is standing between the people of Maine and a violent, dangerous predator. And that’s how I feel today.”

In 2007, she sentenced Albert Dumas to 70 years in prison, with 30 years suspended, for raping and terrorizing a 14-year-old Augusta girl at knifepoint. Mills said the long sentence was necessary to protect society and “to protect the women of Maine from a dangerous sex offender.”

In 2005, she sentenced David Grant to 70 years for killing Janet Hagerthy, his elderly mother-in-law. In imposing a sentence 10 years longer than prosecutors had requested, Mills called the killing “an example of extreme cruelty.”

Mills was the judge of record in a landmark consent decree to improve the state’s mental health system and reduce the number of patients admitted to the Augusta Mental Health Institute.

Twelve years later, in 2004, Mills wrote in a 354-page decision that state officials had failed to meet the terms of the consent decree and should have acknowledged their failure.

“This is not a failure of funding,” she wrote. “This is a failure of management to get the job done.”

Mills has shown the same strict attitude in Strong’s trial. Those involved in the case have been instructed not to talk to the media. Mills reprimanded Lilley on Tuesday for speaking to the media the previous day.

Last week, Mills criticized the media attention after her decision to close jury selection to the public was challenged by the Portland Press Herald. She called the coverage “unprecedented” and said Strong’s trial was the first in which she had not been able to seat a jury in a single day.

“This case has been defined from the very beginning by the interest the media has shown,” she said. “As concerned as I am about the public, the media and the jurors, my paramount concern in this case is that the state receives a fair trial and that Mr. Strong receives a fair trial in this case, and part of receiving a fair trial is that both parties are able to select a fair and impartial jury.”

Mary Ann Lynch, government and media counsel for Maine’s Judicial Branch, said the judicial code of conduct prohibits judges from doing or saying anything that would affect impartiality. Because of that, Lynch said, Mills would not be interviewed for any story related to an open case.

Mills, who usually hears cases in Cumberland and Kennebec counties, was not the first choice to preside over the Kennebunk prostitution case. Justice Joyce Wheeler of Cumberland County was selected, but recused herself in September, forcing the state court system to find another judge.

Since Mills has taken over, the case has been a heavyweight legal fight that has played out in public.

Strong, 57, was arrested in July on suspicion that he helped to run a prostitution business with Alexis Wright, a Zumba instructor in Kennebunk. Wright, whose trial is set for May, was charged months later.

In October, Kennebunk police began charging suspected clients of Wright with solicitation of prostitution. Sixty-six have been charged to date. None of those cases has gone to trial.

Citing the outsized media attention, Mills excluded the public from the jury selection process last week, a decision the Press Herald challenged. The Supreme Court sided with the newspaper, ruling that Mills could not bar the public or media from the proceedings.

Mills then considered Lilley’s motion to drop 46 of the 59 counts against his client — all related to violation of privacy. She dismissed the charges, agreeing with Lilley’s argument that someone who engages in criminal activity — in this case prostitution — does not have an objective expectation of privacy.

The prosecution’s appeal of the dismissal put the case in limbo.

On Monday, Supreme Court Chief Justice Leigh Saufley said the court would need more time to consider the appeal, but authorized Mills to proceed to trial with the remaining 13 counts against Strong if she wished.

Mills said Tuesday that she would wait for the high court’s ruling next month and put the pool of jurors on standby.

Sharon, the defense attorney in Lewiston, said Mills’ decision was in keeping with her style. She “doesn’t shoot from the hip,” and has certainly thought about how best to proceed, he said.

Burke, the law school professor, said that although no judge likes to see decisions reversed, that doesn’t always imply the judge has made a mistake.

McKee, the attorney in Augusta, said that if the high court ends up overturning Mills’ dismissal of the 46 counts, she will simply move on to the next step in the trial.

Staff Writer Eric Russell can be contacted at 791-6344 or at:

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.