What many people know about ice can be boiled down to what they may have learned in elementary school: Ice is water that has changed from a liquid into a solid.

But in the outdoors, such a simple explanation can be dangerously misleading.

“Ice is kind of an unusual material,” said Gordon Hamilton, professor of earth and climate science at the University of Maine in Orono. The quality, thickness, character and reliability of ice as a surface to walk, skate or snowmobile across depends on a host of conditions, including air temperature, the temperature beneath the water’s surface, sunlight and wind. Such factors can combine to turn a magical moment — standing on ice — into a nightmare.

“There’s no way to know that the ice is safe,” said Hamilton. “It’s really tricky to do it on the basis of the weather.” And, he said, it takes experience and substantial skill to look at an expanse of ice and be able to distinguish between areas that are safe and those that are perilous.

That dynamic has been tragically illustrated recently as searchers unsuccessfully tried to locate three snowmobilers, all in their 40s and now presumed dead, who were reported missing in the early morning hours of New Year’s Eve on Rangeley Lake.

A fourth snowmobiler, a woman from Yarmouth, died when her snowmobile broke through the ice at the lake. She had been out on the ice with her 16-year-old son, whose snowmobile also started to break through the ice, though he managed to make it to safety. Her body was recovered the next day.

The three missing snowmobilers were snowmobiling in darkness under whiteout conditions and likely ran into open water, officials have said. Bitter cold and a frozen lake surface in recent days have hampered the search for bodies.

“You really can’t rely on anything, basically,” said Bob Meyers, executive director of the Maine Snowmobile Association in Augusta. When in doubt, he said: “Stay off the ice, stay off the ice, stay off the ice.”

“We have 14,000 miles of trails” on land in Maine, Meyers said. “That is the solution — staying off the ice.”

Many variables contribute to what creates a safe or hazardous frozen lake surface.

“Some of the (Maine) lakes are very large, and if there’s open water and wind, the water is circulating and may be different in different places,” Hamilton said. That translates into different thicknesses of ice, or even a mixture of ice and open water.

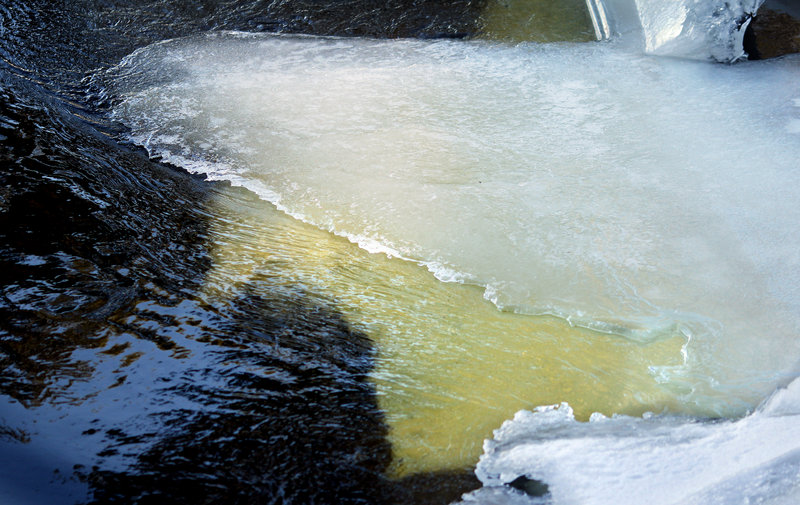

“Wind is bad for lake ice growth and longevity,” Hamilton said, because it mixes water near the freezing point of 32 degrees Fahrenheit with water that might well be warmer. Frequently, a thin layer of the surface can be frozen, but water below can be eight degrees warmer or even higher. At about 40 degrees Fahrenheit, water reaches its densest point and sinks, pushing colder water upward.

That’s a blend that can lead to dangerous conditions because it may create a paper-thin surface, strong enough to hold falling snow but not much more.

And if a lake is capped with ice, Hamilton said, “You keep the water away from the (cold) air and it takes longer for the ice to thicken. And if it snows . . . it further dampens the transfer of heat” from the water into the air, thwarting the formation of ice or its growth, either horizontally or vertically.

Cpl. John MacDonald of the Maine Warden Service has been a spokesman for the agency during the recent search and rescue efforts for the three missing snowmobilers. He said snow and cold weather may give a false impression that ice is safe to walk on.

It’s “that transition from water to land” that can be particularly difficult to discern, MacDonald said. Each day’s weather conditions has differing variables that makes the thickness, quality, strength and color of the ice “different and fluctuating.”

“People don’t become experts at it (evaluating the ice), and our weather fluctuates so much,” said MacDonald.

Now is an especially good time to be mindful of the dangers of ice. Jan. 25-27 is “reciprocal snowmobile weekend” in Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont, according to the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, when legally registered New Hampshire and Vermont snowmobiles can be operated in Maine without a current Maine registration, and vice versa.

MacDonald, a snowmobiler himself, said people should assume nothing.

“You could just as easily go through a thin spot walking” as riding in a vehicle, he said. “You have to be mindful of conditions even walking. Slush can get you into trouble, too.”

Ice at the edge of a freshwater lake, for example, might not be as thick as ice farther out, which might run counter to common sense. Groundwater and runoff from the land could thin the ice at the lake’s edge or even melt it, Hamilton said.

Likewise, a bitterly cold night doesn’t necessarily mean a lake will have frozen over or have an ice cover thick enough to bear the weight of a person. It’s more important to consider the temperatures in the preceding season — how temperatures ran last fall, Hamilton said — because that controls the temperature of the water for longer than people assume.

But most people don’t think about temperatures several months ago when winter arrives and they want to use their cross-country skis, snowmobiles, skates or ice-fishing shacks, he said.

Ice must be at least 6 inches thick before snowmobilers, skaters or trekkers can venture out with confidence, Hamilton said. The wisest thing to do, he said, is “to talk to the locals. … Check with the local game wardens.”

Some local snowmobile associations also do regular checks, boring into the ice and measuring its thickness in several spots, Meyers said, so they can erect small flags to indicate safe crossing points.

Those are essential aides because other measures — like “the sudden occurrence of super-cold weather” — are not a guarantee that a lake’s surface will be frozen to the thickness needed to bear much weight, Hamilton said.

The stalled recovery efforts on Rangeley Lake illustrate the difficulty of determining whether a frozen lake is safe, or whether it will stay frozen long enough to hold all the weight that stresses it: snow, sleet, people, animals and machines.

“If you load it slowly” with weight, Hamilton said, “it flexes. … It bends and accommodates. But if you load it quickly, it fractures.”

Hamilton, who studies ice as part of his work with the Climate Change Institute at the university, spends a month or two each summer in the Arctic and a month in Antarctica. His research focuses on changes to the Greenland Ice Sheet and how they might affect rising sea levels in the Gulf of Maine — and by implication, globally.

He uses a snowmobile in his work, he said, and although he is experienced at using it under different weather conditions, he said, “It scares the crap out of me if I can’t see where I’m going.”

Staff Writer North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6325 or at:

ncairn@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.