WATERVILLE – Here are a few outdated notions: Playing through the pain. Getting your bell rung on the field. Sucking it up. Taking one for the team.

These age-old sporting cliches — used as a rallying cry to “buck up” an injured player — are being tossed aside as coaches, parents and student athletes themselves learn more about concussions and the serious damage they can do to a growing child’s brain.

In Maine, the leading edge of concussion education is in Waterville, at the Maine Concussion Management Institute.

The group — a coalition of Colby educators, local doctors, athletic trainers, neuropsychologists and other professionals — is focused on providing Maine high schools with access to the latest in concussion diagnosis and management tools. In the past year, they have been heavily involved in briefing legislators and creating concussion protocol plans for schools, something all Maine K-12 schools will have to have starting Jan. 1, 2013 under legislation passed earlier this year.

Concussion management is tricky. First of all, it has been difficult in the past to even tell whether a player has been injured. A concussion doesn’t show up on an MRI or a CAT scan. Yet research shows that 10 percent of athletes get concussions.

“It’s hard to manage this injury in an effective way, but we are doing some amazing stuff,” said Dr. Paul Berkner, who co-founded the program.

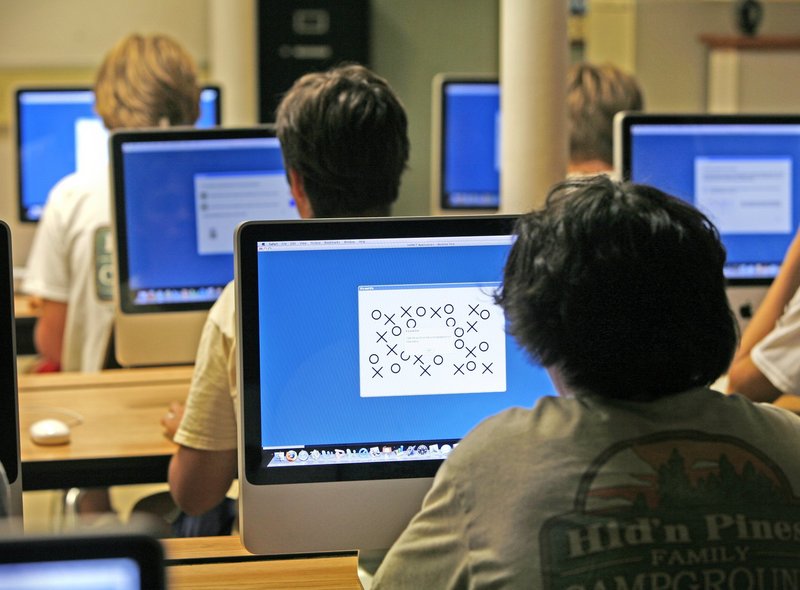

When the institute was launched three years ago, it started aggressively promoting the ImPACT test, a computerized neurocognitive exam that helps determine when athletes who have suffered a concussion can resume physical activity. ImPACT, which stands for Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Testing, is considered the best way to gauge whether a student has been concussed and the severity of the brain injury.

Student athletes take a computerized test that serves as a baseline. If they are injured they get tested again for any measurable change in their response times or critical thinking skills. An injured student might take the ImPACT test repeatedly during recovery, as health care workers determine whether the student’s response times have returned to their baseline norm.

The institute team thinks its work is paying off. More kids are getting tested, school nurses, coaches and athletic directors are working together to help injured students, and parents and students are better informed about concussions. Their primary interest is in getting every high school in the state to use the ImPACT testing program.

“There’s definitely more students coming forward and they’re being checked out,” said Dr. Joseph Atkins, the concussion institute’s treasurer and dean and psychology professor at Colby.

“We’re not anti-sport … we just want to make sure they’re managed properly,” said Atkins, who coached high school football in New York state in the 1980s.

Today, 82 high schools participate in the program, about half of the state’s high schools. About 20,000 baseline tests and 8,000 post-concussion tests have been conducted.

Not only can participating schools access the ImPACT testing resources, but program officials will go to the school to train coaches, talk to the students and serve as a resource for ongoing concussion issues.

The institute was founded in 2009, funded with a grant from Colby College’s Goldfarb Center for Public Affairs and Civic Engagement. Today, it is self-sustaining through fees; schools pay $500 a year to participate.

One of the most important aspects of the institute, said one local school nurse, is that the ImPACT test helps schools determine when an injured student is cognitively able to do anything — including go to class, not just get back in uniform.

It’s been an overlooked aspect of concussion management, said Cape Elizabeth High School nurse Tatiana Green.

“Unfortunately most of the policies have been about return to play, not returning to learning,” Green said. “That piece is really new in the last few years.”

The injured students she sees aren’t even close to being able to concentrate in a classroom. Everything about school — crowded hallways, lots of light and noise, bells ringing — are the opposites of the only real treatment for a concussion: resting the head and eyes.

“These kids, they’re not there, they’re like a deer in the headlights,” Green said of the injured students. “The fluorescent lights, the noise, the activity — it’s so much stimulation. (In the classroom) they hear the humming of the lights, the jingling of the students’ bracelets, the rustling of papers, the people walking in the hallway. They have no filter. They are being stimulated constantly.

“It’s devastating to these students. It’s exhausting just sitting in the classroom,” Green said.

At Thornton Academy, a local doctor looks at all the school’s ImPACT test results and consults with trainers to implement best practices to minimize injury.

“It’s a great tool,” said Athletic Director Gary Stevens. “It gives our trainers data to make decisions, and sometimes data means you have to say no (to a player returning to play.) The more information you have, the more confident you can feel.”

READING THE RESULTS

Berkner and Atkins said they hope that over the long term, they will collect and analyze enough data to be able to use it to loop back to coaches and trainers and develop best practices in either gear or play to prevent concussions in the first place.

For now, the focus is on education and treatment.

“That’s all we have control over,” Atkins said. “You’re not going to tether kids to the couch. All you can control is how to treat it.”

Some trends have become evident — many football and field hockey players get injured, but a surprisingly high number of girls get injured in multiple sports. Neck strength is key to concussions, which may be a reason.

“The more we know, the more we ask questions,” Berkner said. “We always talk about football, but women seen to be at higher risk and have a longer recovery rate.”

Looking at 2010 Maine high school data, the researchers noted that of the top 10 sports with injuries, half were girls’ teams. It appears to be related to neck strength, they said, but more research is needed.

The data show the highest number of post-injury reports was for boys’ football — 399 follow-up tests to 1294 baseline tests — followed by girls’ soccer, with 172 follow-up tests to 860 baseline tests. The remaining top 10 sports, in order, were boys’ soccer, boys’ lacrosse, girls’ basketball, boys’ ice hockey, girls’ field hockey, girls’ ice hockey, girls’ softball and boys’ basketball. Even cross-country skiers had post-injury tests, as did tennis players.

“We need to not focus just on football,” Berkner said. “I don’t think there’s a sport yet that I’ve haven’t seen a concussion. Maybe golf.”

The concussion institute’s other co-founder is Dr. William Heinz, an orthopedist at Orthopaedic Associates in Portland. He said using ImPACT results is particularly useful when trying to tell a parent or a patient that they need to rest the brain and not rush back to school or the field.

Parents who think their child is recovered are sometimes surprised.

“They think everything’s fine, and then I show them he’s at the fifth percentile reaction time,” Heinz. “All of a sudden you see the light bulb go on in their eyes.”

Heinz said the big battle is the culture change. It’s drilled into players to give their all, and parents and coaches want to support and urge on a player. One day, he hopes they will be so successful in educating people about concussions that the culture will change.

“You know how they say friends don’t let friends drive drunk? It should be, ‘Friends don’t let friends play concussed,’” he said.

Stevens agreed. At Thornton, he said, “we’re concerned about the kid who is trying to hide something. With the testing, it’s pretty easy to find out right away.”

MORE CONCUSSION LAWS

Policymakers have also taken note. According to an article this month in the Journal of Neurosurgery, 42 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation to protect young athletes who have sustained a concussion. The earliest youth sport concussion law was enacted in just 2009 in Washington. Ohio’s governor signed a bill into law this week.

Maine’s new law requires every high school soon to develop a concussion management policy for determining when students can return to the playing field and the classroom by Jan. 1. While some schools in Maine already have such policies, under the law all school boards will have to follow similar protocols for diagnosing and treating head injuries as well as training coaches, athletic directors and other school personnel.

Heinz said he’s concerned about implementing the new law, mainly because many schools are being asked to meet a difficult standard.

Specifically, it requires that a student be cleared by a doctor trained in concussion management before returning to school or the field. But for more rural districts, that may not be possible. There is also a need for a school official, likely a nurse, to manage the student’s case — but not all schools have their own nurse, or several schools may share one nurse, making it difficult to handle additional responsibilities.

Further, who should pay for the doctor’s visit? The law applies down to kindergarten-age students, whereas organized sports teams tend to be in middle- and high-schools.

“Talk about chaos,” Heinz said. “The law is being thrown at the schools, how does that help the schools?”

Green works closely with the institute and Heinz, and has also worked with the state to develop model concussion protocol. She, too, is worried about the implementation.

Green agreed, noting that a lone nurse might oversee multiple schools in some districts. The workload of diagnosis, management and follow-up of a concussion is very time-consuming. At her school, she has concussed students check in with her at least once, and frequently twice a day.

“This was done in good faith, but it’s actually going to cause a significant amount of difficulty because of the way the legislation is written,” Green said. “It’s a huge commitment to do it right and to do it well. You need a lot of support.”

Staff Writer Noel K. Gallagher can be contacted at 791-6387 or at:

ngallagher@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.