PORTLAND — Empty boxes. Tatters of paper from cans and jars.

To most people, they’re throwaways.

Not to Maximus “Max” Ngabo, 8, and his mother, Wanda Brann of Portland. To them, discarded containers are carriers of promise, help for their school, Presumpscot Elementary, which doesn’t have a lot of extras to bolster the educational budget for its 280 students.

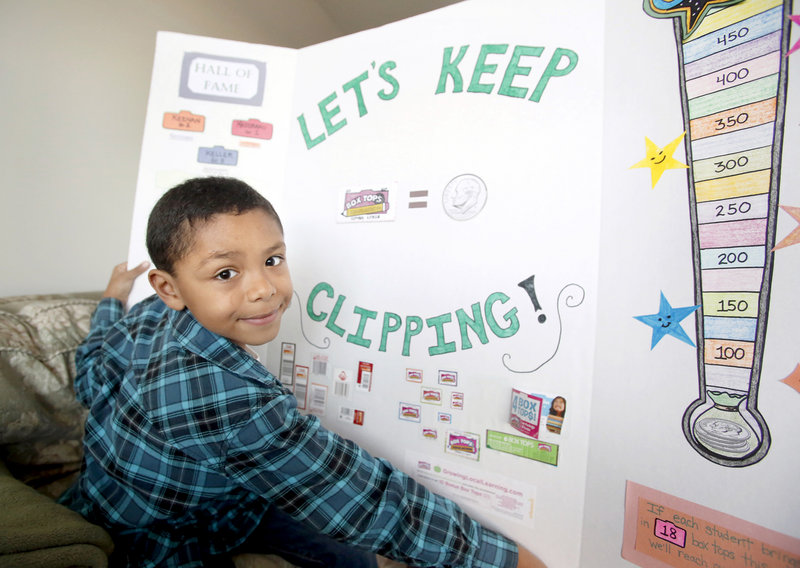

For Max, a young man short on words but long on energy, the bottles and cans and boxes that other people throw away are potential prizes because he is collecting the tops and labels to redeem them for items that can help his school: cash, supplies and equipment.

In the process, Max has formed an unusual bond with some of Portland’s homeless, who saw him collecting items at community recycling bins and began to help with his campaign.

Max’s helpers — who hang out around recycling bins, linger at the soup kitchen, roam the streets — all pitch in, going through the remains of other people’s days, picking up the litter of strangers’ lives, to create new possibilities for Max and his fellow students.

“They literally have a backpack” to hold their lives and possessions, said Brann. “But they think of us as much as they think of themselves, and we think of them as much as we think of ourselves.”

Leading the campaign to collect box tops and labels for Presumpscot has given Max, a bright third-grader who has health challenges including narcolepsy, much more self-confidence over the last year or so. Since he made the effort his campaign, he has learned a lot about himself, his school, his family and the people in his neighborhood and his city.

Max and his mother get up before 6 on weekend mornings to be on the job early at the recycling bins on Somerset and Chestnut streets. There, they spend as much time as they need to paw through trash that, if handled properly, can be used to the school’s advantage.

“We don’t have money to donate to the school, or even buy these products,” said Brann, who works part time in a legal office and serves as Presumpscot’s coordinator for box tops and labels, “but that doesn’t mean we can’t help.”

And help they have. They have lost count of how much they have collected in three years. But Brann said this year’s efforts are going so well that in the first three months of the school year they have collected more than Presumpscot ever collected in an entire year.

Clip-and-save programs — school-corporate partnerships in which parent groups redeem product labels or other proofs of purchase for cash or products — are popular in elementary schools, in part because they encourage participation in the life of the school, foster cooperation and competition among students, and help kids learn reading, math and other life skills.

Since 1996, when General Mills launched the program on cereal boxes, Box Tops for Education has helped America’s schools earn more than $475 million. Within two years of its creation, it had more than 30,000 schools participating. And as Box Tops for Education has grown over the years, all sorts of businesses have signed on, from Hanes and Barnes & Noble to Green Giant and Land O’Lakes.

In Labels for America, the nation’s oldest clip-and-save program, schools participating in volunteer projects, fitness activities or educational programs that promote learning, caring, sharing or students’ nutrition and wellness can receive bonus points.

Created by Campbell’s, the program has generated more than $100 million worth of equipment for U.S. schools.

In Maxian economics, it’s a little more straightforward: box tops are worth a dime, he said, and each label in the Labels for America program gives a school points toward supplies and other merchandise.

“He’s very, very determined,” said Brann, a single mother whose daughter, Alex, 18, also lives in Portland — in a safer neighborhood, her mother says.

She turned to her son, sprawled on his stomach on the coffee table, listening.

“What’s the Presumpscot promise?” she asked him, calling to mind the traits the school tries to engender in students.

“Honesty,” he said. “Um, collaboration. Respect, responsibility, perseverance.”

“There’s one more,” his mother said. “Compassion.”

“Oh, yeah,” he said. “Compassion.”

“It’s so natural, he forgets,” Brann said. “He thinks everybody is compassionate.”

That may explain why Max is so willing and eager to share his collecting efforts. And it might be part of the reason he’s so successful.

Max “is such a strong model of the (school’s) traits,” said Cynthia Loring, principal at Presumpscot, which stresses that character building and student achievement go hand in hand.

Max has been so enthusiastic and his mother has been such “a champion, really, an ambassador” of the program, that the box tops and labels will bring in “thousands of dollars for the first time,” Loring said.

Max talks up his work at the local laundry, the supermarket and anywhere else he can, so he’s on a first-name basis with city workers and many homeless people, with whom he has formed relationships.

“Max doesn’t see homeless people as people to avoid,” Brann said. “He sees them as friends. It’s almost like a family or community. That’s how he views it … Some are veterans; some have illnesses. We’ve met lots of kinds of people.”

One homeless man, named Dennis, is always thinking up new strategies for Max to increase his collections, Brann said. Another, John, is a provider who always makes sure Max has food and warm clothes while he’s collecting items at the recycling bins.

Then there’s Charlie, whom Brann calls “the listener,” because he takes things in and always offers encouragement and support for their work. “They really have a lot of wisdom to share,” she said.

Brann and her family have been homeless themselves, including in one four-month period when they lived mostly out of her car.

They face having to move again, because the three-bedroom apartment in which they live is now beyond their means, because Alex — whom her mother describes as “an activist and humanitarian since she was five” — has left for college.

What hard times and homelessness have taught Brann is that “it could happen to any of us, any day,” she said. “We just try to keep it simple.”

They may have to go without many things that other families take for granted — Max, for example, uses the same backpack he had when he started school four years ago — but love, she said, has made all the difference.

“He loves his school; he loves himself; he loves his community,” she said. “We’re filthy rich in so many ways.”

Staff Writer North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6325 or at:

ncairn@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.