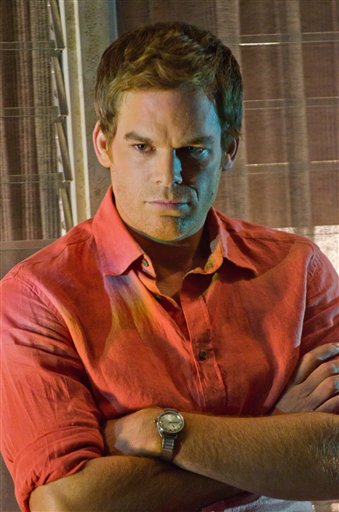

NEW YORK — Well aware that the television audience may be particularly sensitive, the Showtime network aired a disclaimer warning audiences of violent content in the season finales of its dramas “Homeland” and “Dexter” last weekend. It was two days after a gunman killed 26 people in a Newtown, Conn., elementary school.

The political thriller “Homeland” that night featured the burial of a bullet-ridden body at sea and a car bomb that killed scores of people. “Dexter,” about a serial killer, had a couple of murders.

Viewer sensitivity, it seems, was not an issue: Sunday’s “Homeland” was the highest-rated episode in the two years the series has been on the air. “Dexter” was the top-rated episode of any series in Showtime history.

That’s just one illustration of how violence and gunplay are baked into the popular culture of television, movies and video games. While gun control and problems with the mental health system have grabbed the most attention as ways to prevent further incidents, the level of violence in entertainment has been mentioned, too. There have been unconfirmed reports that gunman Adam Lanza was a video game devotee.

In the world of movies, danger is a constant refrain. James Bond has a personalized gun that responds to his palm print in the currently popular “Skyfall.”

“The Avengers,” this year’s top earner with a box office gross of $623 million, features an assassin with a bow and arrow and the destruction of New York City. No. 2 is “The Dark Night Rises” ($448 million), with considerable gun violence including the takeover of the New York Stock Exchange. “The Hunger Games” is No. 3 ($408 million), with an entire premise based on violence — a survivor’s game involving youngsters.

The top-selling video game in November was “Call of Duty: Black Ops II,” according to the NPD Group, which tracks game sales. For players, “enemies swarm and you pop their heads and push forward,” PC Gamer described. The magazine called “Call of Duty” ”Whack-a Mole, but with foreigners.”

The second-ranked “Halo 4” is dark as well, and in the No. 3 “Assassin’s Creed 3,” a game where players get points based on how quickly and creatively they kill pursuers.

NPD did not immediately have the year’s sales figures available. Top video games can earn anywhere between $1 billion and $6 billion in revenue, said David Riley, executive director of the NPD Group.

He emphasized, however, that November’s sales list may be a little deceptive; while “Grand Theft Auto” is among the top-selling video games of all time, the majority of the big sellers are not violent.

The body count piles up on television, too. Seven of the 10 most popular prime-time scripted series this season as rated by the Nielsen company are about crime-fighting, often violent crimes. The series are CBS’ “NCIS,” ”NCIS: Los Angeles,” ”Person of Interest,” ”Criminal Minds,” ”Elementary” and “Vegas,” along with ABC’s “Castle.”

A “Criminal Minds” episode around Halloween was particularly gruesome, involving a woman who kidnapped people to treat her imaginary illness — including a pregnant woman killed for her placenta.

Hollywood often scours its product output to appear sensitive when a tragic event dominates the news, and makes adjustments like the disclaimer Showtime used on Sunday. NBC last Friday said it pulled a rerun of a Blake Shelton holiday special because it had a short animated segment where a reindeer was killed, and told its stations to show a Michael Buble special instead.

To date, there’s been no evidence of a network pulling the plug entirely on a series because of violent content in the wake of Newtown.

Fox is moving forward with “The Following,” a series starring Kevin Bacon that is the network’s most highly-regarded midseason premiere. Based on the first few episodes, the series depicts several murders by stabbing and mutilation. Several young women who share a house are slaughtered. A man is doused with gasoline and set ablaze. A woman kills herself by driving an ice pick through her eye and into her skull.

The question for many who follow popular culture is what the cumulative impact of so much violence is on a user’s brain, particularly someone mentally vulnerable.

U.S. Sen. Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut, questioned on Fox News Channel last weekend, said he believes the violent content causes people who use it to be more violent. President Obama’s adviser, David Axelrod, tweeted that he’s in favor of gun control, “but shouldn’t we also question marketing murder as a game?”

In a junket promoting his new movie “Django Unchained,” actor Jamie Foxx said he believes violence in films does have an impact on society.

His director, Quentin Tarantino, batted down such concerns. “It’s a western,” he said. “Give me a break.” Associated Press movie critic David Germain described “Django Unchained” as containing “barrels of squishing, squirting blood.”

Violence in video games seems more and more realistic all the time, notes Brad Bushman, a professor of communication and psychology at Ohio State University. Video game makers have even consulted doctors to ask what it would look like if a person was shot in the arm — how the blood would spurt out — in order to make the action seem real, he said.

Bushman conducted a study that he said showed that a person who played violent video games three days in a row showed more aggressive and hostile behavior than people who weren’t playing. It’s not certain what the impact would be on people who played these games for years because testing that “isn’t practical or ethical,” he said.

An organization called GamerFitNation has called for a one-day “cease fire” on Friday, asking video game players to refrain from playing violent video games on the one-week anniversary of the Newtown shootings.

Bushman understands the thirst for answers.

“Violent behavior is a very complex thing,” he said, “and when it happens, you want to say what the cause is. And it’s not so simple.”

Lindsay Cross, a Fort Wayne, Ind., woman who writes for the “Mommyish” blog, said it’s important for parents to talk to children about games they are playing and movies they are watching.

“We always want there to be something to do to protect our kids,” she said, and violent media is right there as a convenient scapegoat. “It makes us feel like we’re doing something to help. It’s a natural reaction.”

At the same time, it’s hard to overlook the millions of people who enjoy these games, shows and movies and don’t turn into violent killers, she said.

For whatever concern that politicians and moral leaders show about violent media content, it’s those millions of users and viewers who will ultimately decide whether gore stays on the menu, said Marty Kaplan, director of the Norman Lear Center at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Communication.

If fans lose interest, so will Hollywood, he said.

“Hollywood is exquisitely reactive to the marketplace,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.