FREEPORT – After a month of passenger train service north of Portland, residents from Falmouth to Brunswick are coming to terms with the downsides of the Downeaster.

Heralded as an economic boon before it was welcomed on Nov. 1, the extension of the Boston-to-Portland line now has some officials pondering the impact of the rumbling, clanging, diesel-powered train, and how to preserve quality of life around the railway.

The Downeaster’s schedule includes two round-trips between Brunswick and Boston each day, plus moves without passengers to position the equipment.

The operator of the service hopes to add a third round trip in the future.

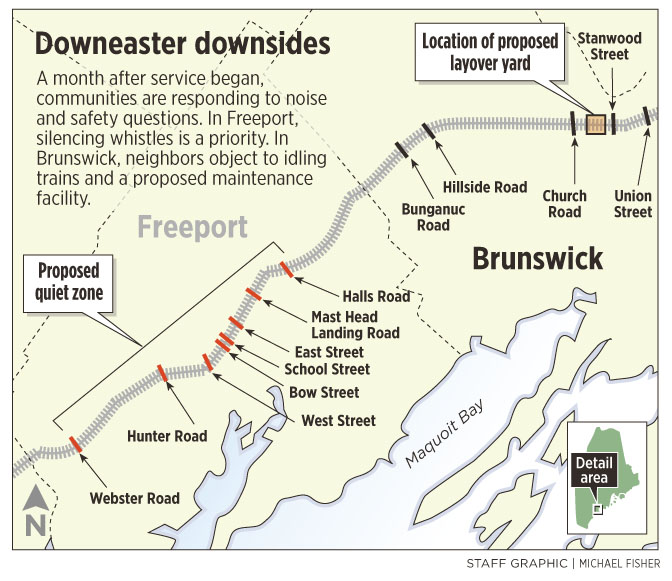

In Freeport, high-decibel whistle blasts and vibrations have rattled residents, businesses and hotel guests, and sparked discussion about creating a quiet zone.

Officials in Falmouth have educated schoolchildren about the dangers of trains, and already have spent money to keep crossings quiet.

And in Brunswick, idling locomotives at the end of the line are angering neighbors and exposing deeper disagreements with the Northern New England Passenger Rail Authority, which runs the Downeaster.

“It’s like every night, ‘Oh God, the train’s coming,’” said Terri Bran, who lives about 150 yards from the train platform in Freeport.

Though she’s partially deaf in one ear, the train still wakes her. “I can’t sleep. I don’t know if I should say anything. I might be the only one who wants it to stop. I would worry if they didn’t have the whistle,” said Bran, conflicted. “I don’t want to see an accident.”

Train whistles can reach 110 decibels, about as loud as a rock concert, a jet taking off or a car horn heard from three feet away. But even in this region that values tranquility, the noisy neighbor has been welcomed. In interviews, town and state officials were careful to laud the extended train service.

In some communities where the train doesn’t stop, the whistles, vibration and air pollution are — sometimes literally — far-off concerns. Faint train sounds even conjure romantic memories. “I’ve heard very, very little” objection, said Nat Tupper, town manager in Yarmouth, “and an awful lot of people saying, ‘This is cool.’“

Helen Kincaid, the resident service coordinator at Oakleaf Terrace, a complex of more than two dozen apartments for people 55 and older that stands feet from the tracks, said the whistles evoke nostalgia for the era of train travel.

“For a lot of my residents, it brings back memories of their childhood, when 100 cars would go by,” Kincaid said. “I haven’t heard any negativity.”

It’s a different story around the rail facility in Brunswick, where neighbors have raised concerns about idling diesel engines.

For nearly five hours each afternoon, the 125-ton locomotives’ engines are kept running to prevent freeze-ups.

That is costly and polluting, and the engines create a palpable vibration for hundreds of feet in all directions, neighbors say.

Mary Heath, who lives on Cedar Street, about 100 yards from where the locomotives idle, said she tries to leave her house each day between about noon and 5 p.m. to avoid the distraction.

“I noticed it right away,” Heath said. “It’s idling right now. It’s like this constant rumble. I wasn’t aware of this change, that it would be idling over here. It would have been nice to have someone say, ‘By the way, a train will be idling in your neighborhood.’ But that’s not how it’s been handled.”

In Falmouth, a police sergeant has presented information to more than 400 schoolchildren about the dangers of rail crossings, and the town has decided to spend $130,000 for more extensive safety equipment at four intersections.

The investments are the first step toward creating a zone where train whistles don’t have to be blown. In Cumberland, where the train passes through but doesn’t stop, Town Manager Bill Shane said, “It’s still new.”

He said people are seeing the train and saying, “‘Oh wow, that’s fast.’ It takes longer for the gates to go down and up than it does for the train to go through.”

Freeport, with eight crossings, faces the highest cost to silence the train. Federal law requires the distinct auditory alerts, even specifying the “one-long, two short, one long” sounding pattern.

Town councilors will revisit the quiet-zone issue on Dec. 18 after weeks of discussion, hearings and research, said council Chairman James Hendricks.

“I have heard some people who say (whistles are) extremely adversely affecting them,” Hendricks said. “Some people say it’s fine.”

Sarah Jacobs, 36, who lives on School Street, said she is acclimating to the noise and schedule. Now, she knows by the evening whistle when to send her kids to bed. “It’s pretty noisy, I have to say,” said Jacobs, motioning to her dog, Digger. “He used to bark every time he heard a train.”

For quiet zones, federal law requires local governments to meet a mathematically determined safety threshold, based on vehicular and train traffic at the crossings, the crossing type, current safety features and accident history.

Freeport’s crossings now have flashing signs, bells, and descending gate arms to block traffic.

That safety equipment was installed as part of the $38.3 million project to replace more than 30 miles of track and upgrade 36 crossings along the new service line. Any towns with railroad crossings add more safety features to establish whistle-free zones.

Some install fiberglass pylons or concrete center barriers, to divide travel lanes leading up to the tracks and prevent drivers from trying to drive around safety gates.

Other ways to meet the standards include installing four-way gates, which block all traffic on both sides of the track, instead of just in the right lane.

Freeport officials could apply for quiet-zone status without adding safety measures because of the relatively scant train traffic, which increases the town’s safety rating.

But if Downeaster service expands in coming years, as planners hope it will, more train trips could nudge the town beyond the limit in the mathematical calculation.

The most expensive and long-term option in Freeport — installing four-way safety gates — would cost more than $1 million, said Town Manager Peter Joseph.

Because Freeport’s roads are narrow near the tracks, permanent centerline barriers appeared out of reach, he said.

The lighter, less sturdy pylons would cost about $120,000, but would be more susceptible to accidental destruction during snow plowing so they would cost more in long-term maintenance. “We don’t want to create a less-safe situation,” Joseph said. “The train whistles play a large role in safety. It’s a big policy question for (the council) to answer.”

Staff Writer Matt Byrne can be contacted at 791-6303 or at:

mbyrne@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.