Gay couples in Maine lead lives that, in many ways, are no different from those of heterosexual couples. They get up and go to work each day, drive children to school or guide them through college, take care of homes and cars, pay bills and taxes, stay healthy, keep in touch with friends and extended family.

But after last Tuesday’s vote legalizing same-sex marriage in Maine, something like the shift of continental plates has happened for many gay couples.

“I can’t tell you how much I’ve cried in the last two days,” said David Jacobs of South Portland, who has been with his partner, Paul Jacobs, for more than 20 years.

“I shouldn’t need other people’s validation,” he said. But being acknowledged as equal in the right to marry healed something in him.

“I don’t think you know what you’re missing until you’re told you can’t have it.”

With Tuesday’s vote, Maine became the first state in the nation to approve gay marriage at the ballot box, by a 53 percent to 47 percent margin. In Maryland and Washington, residents also endorsed gay marriage by voting to uphold gay marriage laws enacted by their legislatures. And in Minnesota, voters rejected a proposed constitutional ban on gay marriage.

The Maine referendum was a milestone in a battle that has been fought for years. That battle included the Legislature’s approval of gay marriage in 2008, which prompted a petition drive by opponents that led to a 2009 referendum overturning the law.

Following Tuesday’s votes, there are now nine states where same-sex marriage is legal: Connecticut, Iowa, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Vermont and Washington, and the District of Columbia.

David Jacobs, 48, a marketing and development consultant, and Paul Jacobs, 47, a software developer, had not “wed” in the way that many gay couples opted to before same-sex marriage became legal. They had no commitment ceremony or other ritual to substitute for a wedding.

After Sept. 11, 2001, however, David gave up his birth family’s name and took Paul’s. They had been touched by the fact that the relationship of a gay couple aboard one of the planes that crashed into the World Trade Center went unacknowledged in the aftermath — as did their adoption of a son — because they did not share the same surname.

But David and Paul did not otherwise publicly document their commitment to each other. “We are not married,” David said. “We have been waiting until our own state said it was legal.”

Now that Maine has approved it, David and Paul already have set a date: July 7, 2013, the 23rd anniversary of their first date. They plan to hold their wedding in the backyard of their South Portland home.

WITH VOTE, AN ENGAGEMENT

For Rodney Mondor and Ray Dumont of Portland, the change occurred as soon as the vote was announced. The couple — both work as administrators in student services at the University of Southern Maine — got engaged right at the victory celebration Tuesday at Holiday Inn by the Bay in Portland, where supporters gathered to watch referendum returns.

As expected, it was Mondor, 45, who proposed.

“I insisted,” said Dumont, 46. “I told him, ‘I want you to ask me.’ It’s a little old-fashioned, I know. I am old-fashioned about it.”

Mondor phoned ahead to his partner’s mother in Lewiston and put the call on speaker phone. He asked her for permission to marry her son; she gave it. And there, with Dumont’s mother listening, Mondor proposed.

“That moment was really special — very exciting,” Dumont said. “It was very romantic.”

There was no exchange of rings; they had done that after they had been together for a year. Mondor did not get down on one knee or in any other way acknowledge the traditional heterosexual proposal ritual.

“He drew the line at that,” said Dumont. “He said, ‘Let them (the straight world) have that.’“

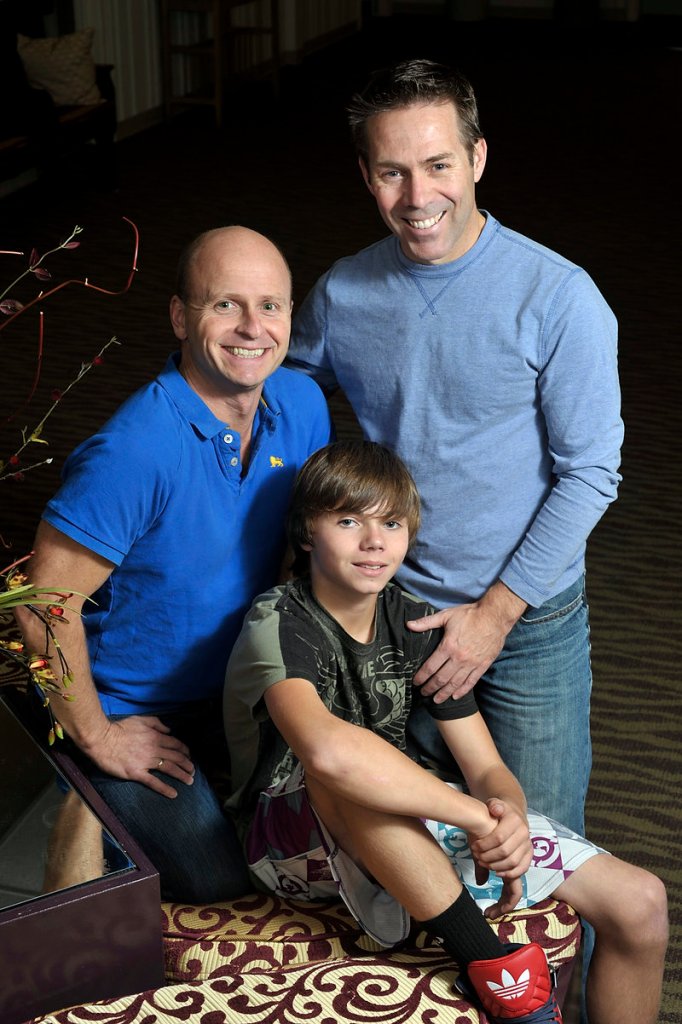

Still, for Mondor and Dumont, and for their 13-year-old son, Ethan, being able to marry legally and have that recognition means that what for years has defined their family — their own circle of love, support, commitment and the work and play of a day-to-day life — now also has been “recognized” by the state and the world beyond their family, friends and acquaintances.

The wedding probably will happen sometime next year, Mondor said, and “it’s going to be huge,” because so many people have already said they’re coming. The couple have not decided where the wedding will take place; Mondor admitted they felt momentarily “that knee-jerk reaction” to go right to City Hall for a ceremony.

“But it’s a very serious thing to show our commitment, to show our love,” he said. So, even after the long wait for legal sanction, they will hold off a little longer — to get things just right.

Meanwhile, everyday life has already returned to normal. “Everything in our life is still the same,” Mondor said.

“We’re still chasing (Ethan) to do his homework,” said Dumont. “Still getting him to basketball practice.”

The men already have created a sense of family in the usual ways; Mondor’s been a part of the PTA since Ethan was in kindergarten and has served as a coach for sports teams, too. They also twice went through the process of adoption, first in 2004, when the state allowed only one partner — in this case, Mondor — to hold the status of a parent, while Dumont became a guardian. Subsequently, Maine recognized the right of equal partnerships in such adoptions, and now both are legal parents to their son.

But winning the right to legally marry adds another dimension, for them and in the eyes of the world, Mondor said. “We’re making it real.”

A SYMBOL OF COMMITMENT

For Denise LaFrance and Sherry Dunkin of South Portland, legal marriage will be yet another symbol of a lifelong commitment they made seven years ago in a ceremony that “was very much a wedding for us,” LaFrance said. As for what and how they might legalize that bond now, “honestly, we haven’t talked about it.”

“With the last vote,” which in 2009 repealed the right of gay couples to marry, “so many people were so devastated,” said LaFrance, 52, a life coach who counsels women on mid-life transitions, from coming out to making career changes. This time around, “we were hopeful but cautious, really cautious.”

But with the way cleared to publicly embrace “the civil, legal piece” of marriage, “the conversations (about whether to marry) will happen now” throughout the gay community, she said. “I’m sure we’ll have the conversation now.”

“It won’t change anything day to day,” LaFrance said. But she believes there are three aspects of gay life that will shift dramatically, if quietly, by normalizing same-sex marriage identity within the larger culture.

“One, having the relationship be recognized” will make a profound difference in how people feel about themselves and their lifelong committed relationships, she said.

“Two, the legal protections (won’t) be questioned, and three, for the kids,” she said. Legal marriage will be a validation that their families are as valued and worthwhile as any other.

Sea changes like these demonstrate why the right to marry and to be viewed under the law as equal to heterosexual couples means everything to people who in the past have been excluded.

“Every time I think about it, I cry,” LaFrance said. It might seem to people outside the community to be a “strange validation, but it matters because we’re human. (Our) emotion is right on the edge. The life of being gay is easier because of the vote this week.”

Marriage “really doesn’t change (things) for us emotionally,” LaFrance said. She and Dunkin, 54, an IT manager, have a “tight-knit group” of friends, most of whom have been in long-term relationships — 33 years in the case of one couple. Most of them have already put in place legal protections for one another concerning health care and inheritance, for example.

Some long-standing couples, LaFrance said, will look at legal marriage and say, “Why bother?” For them, “it will be a question of whether the benefits outweigh the costs.”

But for others, she said, marriage will represent both an end to the sense of “we’ve waited for so long” and a beginning of a publicly sanctioned and recognized “lifelong commitment.”

“There may be a certain amount of social awkwardness” as couples adjust to the landscape of legalized marriage, she added, because “the gay community is as diverse as the straight community.”

“The terminology is going to be really interesting,” LaFrance said, admitting herself to “some trepidation about using the term ‘wife’” to describe her life partner.

“For so many people, they’ve craved that for so long,” she said. “To be able to say those words” — husband or wife — will be very important to gay men and lesbians.

“Partners come and go,” LaFrance said. But even “life partner” — while it attests to a “death-do-us-part kind of thing” — doesn’t have the same impact as “wife,” which to her bespeaks a more permanent and total commitment.

“It’s not a gender-role thing,” she explained. The pairings will be wife-to-wife and husband-to-husband, not husband and wife.

The traditional male-female gender roles and how those are navigated “is part of the negotiation” in same-sex relationships, more so than for heterosexual couples, LaFrance said. In some ways, it’s the “opposite of the straight world,” because roles and expectations are not as clearly delineated.

“What we see in the community will be about names,” LaFrance said. “I wonder if (people) will take a partner’s name. I wouldn’t be surprised if we see whole new trends starting.”

Staff Writer North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6315 or at: ncairn@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.