SCHENECTADY, N.Y. — It’s scratchy, lasts only 78 seconds and features the world’s first recorded blooper.

The modern masses can now listen to what experts say is the oldest playable recording of an American voice and the first-ever capturing of a musical performance, thanks to digital advances that allowed the sound to be transferred from flimsy tinfoil to computer.

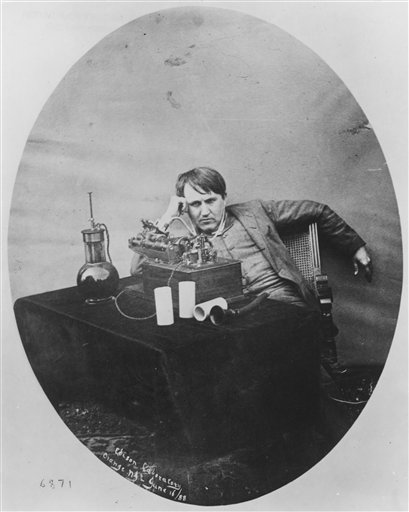

The recording was originally made on a Thomas Edison-invented phonograph in St. Louis in 1878.

At a time when music lovers can carry thousands of digital songs on a player the size of a pack of gum, Edison’s tinfoil playback seems prehistoric. But that dinosaur opens a key window into the development of recorded sound.

“In the history of recorded sound that’s still playable, this is about as far back as we can go,” said John Schneiter, a trustee at the Museum of Innovation and Science, where it will be played Thursday night in the city where Edison helped found the General Electric Co.

The recording opens with a 23-second cornet solo of an unidentified song, followed by a man’s voice reciting “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and “Old Mother Hubbard.” The man laughs at two spots during the recording, including at the end, when he recites the wrong words in the second nursery rhyme.

“Look at me; I don’t know the song,” he says.

When the recording is played using modern technology during a presentation Thursday at a nearby theater, it likely will be the first time it has been played at a public event since it was created during an Edison phonograph demonstration held June 22, 1878, in St. Louis, museum officials said.

The recording was made on a sheet of tinfoil, 5 inches wide by 15 inches long, placed on the cylinder of the phonograph Edison invented in 1877 and began selling the following year.

A hand crank turned the cylinder under a stylus that would move up and down over the foil, recording the sound waves created by the operator’s voice. The stylus would eventually tear the foil after just a few playbacks, and the person demonstrating the technology would typically tear up the tinfoil and hand the pieces out as souvenirs, according to museum curator Chris Hunter.

Popping noises heard on this recording are likely from scars left from where the foil was folded up for more than a century.

“Realistically, once you played it a couple of times, the stylus would tear through it and destroy it,” he said.

Only a handful of the tinfoil recording sheets are known to known to survive, and of those, only two are playable: the Schenectady museum’s and an 1880 recording owned by The Henry Ford museum in Michigan.

Hunter said he was able to determine just this week that the man’s voice on the museum’s 1878 tinfoil recording is believed to be that of Thomas Mason, a St. Louis newspaper political writer who also went by the pen name I.X. Peck.

Edison company records show that one of his newly invented tinfoil phonographs, serial No. 8, was sold to Mason for $95.50 in April 1878, and a search of old newspapers revealed a listing for a public phonograph program being offered by Peck on June 22, 1878, in St. Louis, the curator said.

A woman’s voice says the words “Old Mother Hubbard,” but her identity remains a mystery, he said. Three weeks after making the recording, Mason died of sunstroke, Hunter said.

A Connecticut woman donated the tinfoil to the Schenectady museum in 1978 for an exhibit on the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Edison company that later merged with another to form GE. The woman’s father had been an antiques dealer in the Midwest and counted the item among his favorites, Hunter said.

In July, Hunter brought the Edison tinfoil recording to California’s Berkeley Lab, where researchers such as Carl Haber have had success in recent years restoring some of the earliest audio recordings.

Haber’s projects include recovering a snippet of a folk song recorded a capella in 1860 on paper by Edouard-Leon Scott de Martinville, a French printer credited with inventing the earliest known sound recording device.

Haber and his team used optical scanning technology to replicate the action of the phonograph’s stylus, reading the grooves in the foil and creating a 3D image, which was then analyzed by a computer program that recovered the original recorded sound.

The achievement restores a vital link in the evolution of recorded sound, Haber said. The artifact represents Edison’s first step in his efforts to record sound and have the capability to play it back, even if it was just once or twice, he said.

“It really completes a technology story,” Haber said. “He was on the right track from the get-go to record and play it back.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.