PORTLAND — You see them holding cardboard signs on a street corner, or waiting in line for a hot meal.

Portland’s homeless population, shelter officials say, is at record levels and straining their ability to care for those in need.

Officials attribute the recent rise in homelessness mostly to the loss of the city’s Homelessness Prevention, Rapid Re-Housing Program, which ran out of federal funding last November.

The two-year program, funded by $876,000 from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, paid for seven full-time employees and provided rental assistance and support services.

As a result of the loss, people are spending more time in city shelters, officials say.

From Oct. 1, 2011, to Oct. 1, 2012, the Oxford Street Shelter was full every night except one, said Douglas Gardner, the city’s director of Public Health and Human Services. That’s up from 170 capacity nights during the previous year.

Most nights, the Preble Street Resource Center is used to house an overflow of up to 75 people, and the city’s General Assistance office is increasingly used as an overnight shelter for up to 50 people.

Gardner said the General Assistance office was used 35 times in the past year as an emergency shelter.

A task force appointed last year to develop strategies for preventing homelessness in Portland will present its findings to the City Council on Monday.

The report makes several recommendations that it says could save about $2.2 million a year in emergency care, but acknowledges that it would take “a significant investment on the part of many different organizations” to make that happen.

Portland has had a policy of not turning away anyone seeking shelter since 1987, when then-City Manager Bob Ganley instituted the rule after a homeless encampment sprang up at City Hall to protest the closure of a shelter.

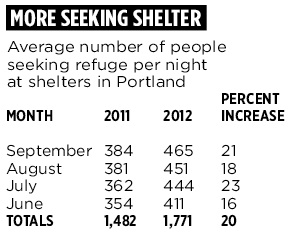

Since June, nightly homeless figures have been up by nearly 20 percent from the previous year. And there’s no indication the increasing demand will change anytime soon, said Josh O’Brien, director of the Oxford Street Shelter.

So who are these people? Where do they come from? What are they seeking?

According to intake records and shelter staff, the people using the Oxford Street Shelter are divided evenly between three groups: Portland residents, Mainers from other towns, and people arriving from out of state.

Portland residents use the shelter for a variety of reasons, but many who are homeless struggle with mental illness and substance abuse. Most out-of-town homeless come to Portland because their community doesn’t have a shelter or because theirs is full. Many out-of-state homeless say they come here specifically for the city’s housing services.

Here are the stories of people from each of those groups.

THEÂ LOCAL: City man faces chronic struggle with his demons

The last time 40-year-old James Lamoin had any stability in his life was when he was a teenager, living on Washington Avenue with his family.

Since then, Lamoin, a heavyset man with a big beard who carries his belongings in a black trash bag, has been battling his personal demons. He suffers from paranoid schizophrenia and diabetes. He also struggles with drug and alcohol addiction.

Lamoin said he gets by on disability checks, food stamps and Section 8 housing vouchers. There is currently a waiting list for low-income housing.

In April 2010, he became homeless when a fire forced him from his apartment. He stayed with his brother on Munjoy Hill for a month, but had to leave because he wasn’t on the lease.

Eventually, he secured housing on Park Avenue, but he was evicted in September because police were frequently called to respond to violence — he says by other people in the apartment he shared — and drug and alcohol use.

Lamoin said high-gravity malt liquor with the brand name Hurricane, crack and marijuana were favorites on Park Avenue.

“I still struggle with it,” he said of his addiction. “It seems to be a big issue for me. I keep asking for it and just want more and more. When it’s not available I make a big issue out of it. When it’s not available I get upset about it. It seems to make people crazy, that stuff.”

Lamoin doesn’t blame anyone but himself, though.

“Nobody’s forced me to do it,” he said. “Nobody’s put a crack pipe to my mouth, or the weed or the beer.”

After his eviction, Lamoin sought refuge at the Milestone Foundation, a so-called wet shelter for those with substance abuse issues. But he had a mental breakdown, he said, and was sent to Spring Harbor Hospital to be treated for his schizophrenia. While at Spring Harbor, Lamoin said he lost about 20-25 pounds and played basketball every day. Lamoin said he was put on some medication, which seems to be helping, and was released. He now stays at the Oxford Street Shelter, waiting for Section 8 housing.

“I’m glad I can come here at night instead of being on the street,” he said.

Lamoin said he has already fallen back into his familiar habits. He was caught drinking a beer at the Oxford Street Shelter and was reprimanded by the staff.

“They told me if I do that again I can’t come back here,” he said. “I’ve heard of people being banned from here for life.”

Without that structured living environment, Lamoin doesn’t see any path out of his situation.

“It’s a hard road ahead,” he said. “It seems like I need long-term treatment.”

THEÂ OUT-OF-TOWNER: Young couple struggles after housing setback

Michael Cohen, 26, grew up in Biddeford and moved to Belfast to live with his fiancee. They were on the verge of starting their life together when a bed-bug infestation suddenly forced them from their apartment building.

Caught off guard, the couple didn’t have the money to secure a new apartment — which typically requires a security deposit and first and last months’ rent. The local YMCA has 30 beds for those in need of shelter, but it was always full.

“It’s not really even a shelter,” he said.

After spending a month or so couch-surfing, the couple came to Portland seeking a better opportunity.

Cohen stands out at the Oxford Street Shelter. A young man, he is full of energy and is articulate. On this day, he was well-clothed, wearing relatively new sneakers, an equally pristine baseball cap, a polo shirt and silver chain.

His fiancee, 20-year-old Faith, was staying at the Lighthouse Shelter, where she was provided a bed, rather than a thin mat to lay on the floor. Cohen was forced to stay at Oxford Street because he was too old to stay at Lighthouse.

“I’m not an alcoholic and I don’t do drugs,” he said. “I don’t like being around this stuff, but you have to do what you have to do and make the best of it.”

The worst three nights since the couple was forced from their apartment were spent wandering the streets. One of those nights, they ended up staying in the hallway of a friend’s house.

Cohen said Faith has already landed a job in Portland as a certified nurse at a local hospital. With a background in sales, Cohen hopes he will soon have a job as well. He has been looking for work through local staffing agencies.

He doesn’t expect to be at the shelter long — just long enough to save enough money to find low-income housing. Adding urgency to the search is the fact that he is currently fighting for custody of his two young daughters from a previous relationship.

“I’m starting to pull ahead in that situation and I have ended up in this situation,” he said. “We’re really just trying to find something as soon as possible.”

He has since moved on, after spending seven nights at the shelter, according to the shelter director.

Cohen did not report his reason for leaving.

THEÂ OUT-OF-STATER: Massachusetts woman gets a break with job

Originally from Massachusetts, Susan Passerello has been struggling with homelessness since 2002, when her ex-husband, Robert, passed away.

“Robert was the note winner,” she said of the carpenter. “When I met him, he took care of everything. I got used to a certain way of living.”

Unfortunately, that lifestyle was funded through credit. Passerello said she racked up $30,000 in credit card debt and assumed another $35,000 in an auto loan.

Passerello, who had two children from different fathers, said she had hoped to pay down the debt using alimony from Robert, but he passed away shortly after their divorce. She tried to hold it all together by working seasonal odd jobs and renting hotel rooms by the week, but everything fell apart.

“I got sunk in a hole of material objects,” she said. “Everything just dominoed. I tried to keep it afloat, but I lost everything.”

Passerello, 52, remembers her first night on the streets of Swampscott, Mass. She had always been part of the shopping masses, but suddenly she felt like she was on the outside looking in. It was too tough for her 4-year-old daughter, who wound up staying with Passerello’s sister. But her son, who was 12, stayed by her side. He has since graduated from college with a mountain of debt and is now working at Home Depot.

After losing everything, Passerello tried staying in shelters in Massachusetts, but she didn’t feel safe. She said she doesn’t struggle with alcohol or drugs, so the state didn’t seem to be able to help her much.

“I couldn’t handle Massachusetts,” she said. “The shelters were really raw, they were hard, and they had no services. Any kind of services were basically for people with drugs and alcohol.”

She came to Maine, a state she had visited and enjoyed over the years, looking for housing services, initially spending time in the Biddeford-Saco area. She applied for housing assistance through several agencies, but when she left the state for a period of time, she became ineligible for housing.

As of Sept. 10, Passerello had been staying at the shelter for three weeks. She said the staff was compassionate, but she could not say the same for the people and businesses of Portland, who she said were openly rude to her as she walked the streets wearing a backpack.

But since then, things have started to turn around. On Oct. 11, Passerello said she landed a full-time job at a local seafood processing company and received an application for a Section 8 housing voucher.

The break came not a moment too soon.

“I can’t handle it here,” she said, noting the prevalence of drugs, alcohol and mental illness at the shelter. “This will break you down into nothing.”

Staff Writer Randy Billings can be contacted at 791-6346 or at:

rbillings@mainetoday.com

Twitter: @randybillings

Send questions/comments to the editors.