ON THE SHORE OF MILLINOCKET LAKE — Frederic Church knew what he was looking for when he arrived on the south shore of Millinkocket Lake in the waning days of summer 1878.

The view.

He was familiar with this terrain, and had spent many years tromping in and around Mount Katahdin.

But this time, he meant to stay.

He purchased the 400-acre Stephens Farm, which offered unobstructed views across the lake to the mountain. For the 20 years that he owned the farm, Church explored the mountain in all its moods and visual glory. He sketched, painted and otherwise portrayed Katahdin hundreds of times, creating sweeping landscapes of Maine’s most sacred mountain.

Along with Winslow Homer, Church is considered among America’s most accomplished landscape painters. Just as the rocks and water at Prouts Neck became Homer’s late-career muse, the woodlands and the ever-changing colors of Katahdin were that for Church.

Their time in Maine overlapped. Church bought the farm near Katahdin in 1878; Homer moved into the studio at Prouts Neck five years later.

Whereas Homer stayed at Prouts Neck until his death in 1910, Church visited his farm at Katahdin mostly in the summer and fall for about 20 years. He sold it to his son in 1898, and died two years later at age 73.

Because this place was important to Church, it remains important in the history of American art. He sought it out because it gave him visual access to the mountain and allowed him to pursue his subject at his vigorous will. Other than Church’s majestic home at Olana, N.Y., the 400 acres at Millinocket Lake was the only property the artist owned.

The farm has been improved and developed in the century since, although it is still powered by a generator and water comes from a local spring. A portion of the original rugged log cabin remains standing.

The camp is owned by the Woodworth family and tended to by Raymond “Woody” Woodworth and his girlfriend, Jen Hall.

Woodworth’s parents, Ray and Muriel, have owned the camp for years, and live off the grid a few doors down. Woodworth’s grandfather, Elmer Woodworth, worked for Church’s heirs and tended to the camp. He purchased it in 1953.

Lately, with attention being paid to Church and his time in Maine, Woodworth and Hall have become acutely aware of the legacy of this place, and have begun sharing it with artists who follow in the footsteps of the artist. They enjoy showing off the small portion of the original camp that remains, as well as details of the wing that Church’s son built after acquiring the place.

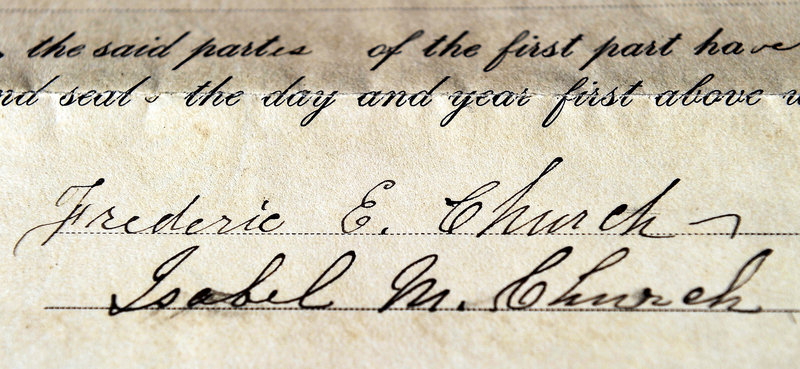

They call attention to the stone mantle of the fireplace, built with rocks that roughly form the outline of Katahdin itself. Delicately, they unfold tattered, century-old deeds with Church’s signature, proving his purchase of the camp — for $112.50 in 1878 — and later his sale of the camp to his son for $1.

In a letter dated Nov. 29, 1878, Church announced his purchase to a friend: “I have just completed a small picture of Khaadn — I have purchased the Stephens Farm — Lake Millinocket — and have received the deed.”

Reproductions of Church’s Katahdin paintings hang on the walls, and Hall jokes that they continue to search the rafters for a wayward original. “Don’t we wish,” she said with a laugh. “And we’re always looking.”

Evelyn Dunphy appreciates those sentiments. A watercolor painter from West Bath, she has made paintings of mountains all over the world. She has felt kinship with Church for many years, based first on his paintings of Greenland.

In the last decade or so, she has pursued Church’s deep connection with Maine and Katahdin. A mutual friend introduced Dunphy to the Woodworths and their homestead. The first time Dunphy arrived at the camp, she gasped at the view of the mountain looming four miles across the lake.

“It does pretty much bowl you over. There is no bad view of Katahdin, but this is the most beautiful spot. This is why Church came here. It’s so obvious when you see it,” Dunphy said.

A SPIRITUAL EXPERIENCE

As she has spent more time at the camp, Dunphy has come to understand something about Katahdin that is almost unknowable without the experience of being immersed here for extended periods.

Dunphy and her husband stay in a small, open-sided cabin at lake’s edge that looks across at the mountain. The mountain dominates her view and conscience the whole time she is here.

It’s not the shape of the mountain — although the triangular shape of Katahdin is an unusual characteristic. It’s not even the changing colors — although the shift in colors from purple to orange, and sometimes to misty white when it’s lost to the weather, forces a painter to sketch quickly.

The draw is more spiritual than tangible, she said, and is something close to what Thoreau meant when he wrote of Katahdin: “primeval, untamed, and forever untameable Nature.”

Of the many mountains Dunphy has climbed and painted, Katahdin is the one “I love the best above all. The farther north I go, the happier I am. There is no place I would rather go than north,” said Dunphy, who was raised in Nova Scotia. “In Maine, Katahdin represents that to me.”

Three times a year, she leads plein-air painting workshops at the Church camp, inviting artists from across the country and occasionally from overseas to come up to Katahdin for a few days to sketch and paint. For many, the lure of the workshop is the chance to paint where Church painted. His legacy inspires them, and perhaps intimidates them as well, at least at first.

But inevitably, as time goes on, the lure becomes the mountain itself.

“It’s interesting to see where Church painted, as far as the history and the scenery,” said Sandra Pye of Phippsburg, one of five students who enrolled in a four-day September workshop.

But Pye’s presence here is not about pursuing a history lesson. It’s about learning to be a better painter, and Katahdin offers a willing and challenging subject.

The students arrive soon after noon on a Thursday, and quickly unpack their gear into the cabins where they will stay for three nights. Dunphy assembles them in the backyard of the main cabin. The weather forecast is iffy, and she wants them to get to work right away sketching. If it rains, they can use their sketches to work from while painting inside.

The wind is blowing hard, and the students scatter about the property, some wearing heavy jackets and gloves.

For Bernard Zeller of Putnam, N.Y., coming to Katahdin means following in the footsteps of Church. He’s interested in channeling Church’s source of inspiration — or as Zeller calls them, “his motives” — and to stand “in the place where the artist painted and see what he saw.”

After a few hours, what struck him was the changing light on the side of the mountain. It forced him to work quickly, and to pay close attention to the details of his subject. “The light is fantastic out here,” he exclaimed.

Jamie Walker of Naples appreciates Dunphy’s painting style, and wants to learn from someone whose work she likes and respects. Painting where Church painted offers added meaning to the experience, she said.

After her students worked on their own for a few hours — breaking only to warm themselves with hot tea by a roaring fire — Dunphy brings them together in front of her easel for a quick demonstration. In a matter of a half-hour or so, a painting of Katahdin began emerging on her paper — not by magic, but by the sheer power of inspiration.

“I’m convinced Church came here because of this mountain,” Dunphy said, directing her gaze across the lake to the cloud-shrouded Katahdin. “He painted mountains in South America. He painted mountains in Asia. He could have painted anywhere in the world.

“But he painted here. It was this mountain that captured his imagination.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.