We can learn a lot about Winslow Homer by paying attention to the place where he lived.

The painter’s studio, situated just a few feet from the ocean at Prouts Neck, says as much about the man himself as it informs the work that he did there during the last 27 years of his life.

This was his private place, where he painted, slept and ate his meals.

In the fall and early winter, when the surging seas lashed the rocks just outside the door, it’s easy to imagine Homer huddling up to the fireplace and heating a kettle of water for a warm drink.

On those moonlit nights, we can picture him bounding the stairs and making his way to the open-air, second-story piazza that opens to the sea.

It’s fun to think of him on those glorious summer days picking his way among the granite ledges with a sketch pad, furiously making marks on paper that would later become a majestic oil seascape.

These scenes we have to imagine, because Homer was a private man. He didn’t do many interviews. “The important thing is my work, not my life,” he once said. “It is of no importance to others.”

But he left a lot behind that enables us to paint a picture of him.

Homer was close to his family — especially his older brother, Charles, who had a much grander house just next door. Homer and Charles often fished together, and we see evidence of that in family photos and fishing paraphernalia that are on display at the studio.

Homer never married and had no children, though descendants of his brothers still live in Maine.

Over time, mythology has suggested that Homer was a recluse who chose a rugged life on the Maine frontier. But that image is misleading.

Homer had plenty of company on Prouts Neck — sometimes too much. He warded off unwelcome visitors with a hand-painted sign that said “Snakes — Snakes! Mice!” That sign survives, and is part of the studio tour.

One day, according to legend, Homer was out on the rocks sketching when a stranger approached and asked, “Do you know where I can find Mr. Homer?”

Playing coy, the artist replied, “What’s it worth to you?”

“Fifty cents,” the man said.

“Let’s see it,” Homer answered. “You’re looking at him.”

Homer was an urbanite with high-society taste. He was born in Boston, and furnished his New York home and studio ornately with bearskin rugs, velvet curtains and Chinese vessels.

The studio at Prouts Neck includes items from his New York abode as a way of reminding visitors that his life was not always as rugged as it is sometimes portrayed.

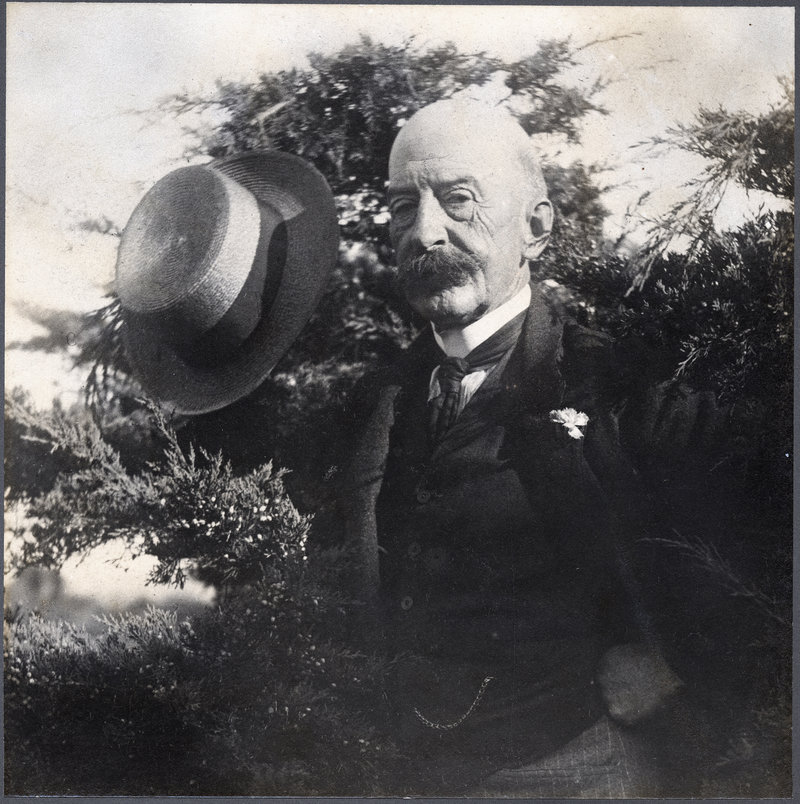

Appearance mattered to Homer. In most photos that survive, we see him as a dapper dresser who’s well groomed, with a balding head and big mustache. He liked good clothes and fine things.

His studio was not insulated, but Homer did not rough it. He left Maine before winter set in, usually heading south to Florida, Bermuda or the Bahamas. Like the snowbirds of today, he returned in the spring when the weather became agreeable.

By the time Homer came to Maine, he was already a successful artist, both commercially and critically. He was known on both sides of the Atlantic, and was one of the first American artists to gain respect in the European painting capitals.

He earned his early-career reputation as an excellent illustrator. He covered the Civil War for Harper’s, which sent him to the front lines to sketch the commanders and camp life. After the war, he concentrated on painting, and quickly developed an international reputation.

Homer arrived at Prouts Neck in 1883 at age 47, and stayed until his death in the studio on Sept. 29, 1910, at age 74.

He was not in good health at the end. Over the final five years of his life, he suffered various ailments, including kidney disease and pneumonia. He had a stroke near the end of his life, and there is talk that his eyes were going bad.

Until the end, mostly what he did at Prouts Neck was paint.

That was his place, and it was where he dedicated the final phase of his life to making some of the most important work in the history of American art.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.