Karen Sherry felt spellbound last week when a team of gloved couriers and art preparators removed the Winslow Homer oil painting “On a Lee Shore” from its wooden crate and prepared to place it on the wall at the Portland Museum of Art.

Inch by inch, foot by foot, the painting revealed itself as workers lifted the heavy framed canvas from its wrappings. The force of he churning green waves, white with foam and crashing hard against the rocks, came into view. It nearly staggered Sherry, the museum’s curator of American art.

“You finally see the painting live, and standing in front of it, you can fully appreciate its visual impact,” she said. “There is such complexity to its surfaces, to its compositional design. You can really feel the scale of the work and how you as a viewer relate to the work. You can look at a painting like that for a long time in a book or on the computer. But you can only get that sensual experience when you look at it live in the gallery.”

On Saturday, the Portland Museum of Art formally opens one of the most ambitious exhibitions in its history: “Weatherbeaten: Winslow Homer and Maine.” The exhibition includes 38 paintings, watercolors and etchings that Homer made while living nearby at Prouts Neck in Scarborough.

The American artist lived there from 1883 until his death in the studio in 1910. In tandem with the exhibition, the museum will open Homer’s studio to the public, the result of an extensive six-year preservation project. The museum will offer guided tours of the studio beginning Sept. 25.

With so much attention paid to the studio and the museum’s extensive preservation effort, it’s easy to overlook what the hoopla is about in the first place: Homer was a very fine painter, perhaps the most accomplished painter of nature in American art history.

“Weatherbeaten” confirms that status.

THE PROUTS NECK YEARS

This exhibition examines Homer’s career with a tight focus on his 27 years in Prouts Neck. Aside from its remarkable simplicity, the distinguishing feature of Homer’s studio is its location. It’s situated a short distance from the rocks, and looks out with a sprawling view of the Atlantic Ocean.

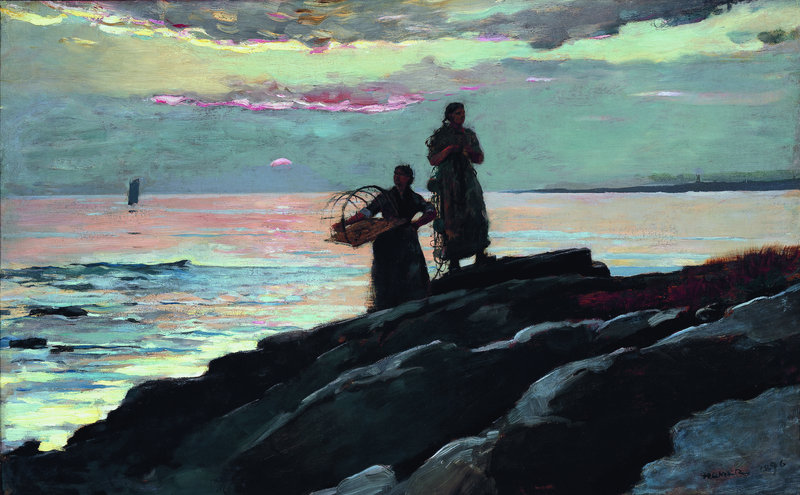

Homer capitalized on that view. As he settled into his life in Maine, he populated his paintings with human activity less and less as he focused his attention on the landscape and dramatic seascapes. Human figures still showed up in his work, but played a smaller role.

Instead of happy young people celebrating America’s youthful spirit as some of his earlier painting had done (perhaps most famously in “Snap the Whip,” 1872), these late-career works depict fishermen and their wives tending to nets or looking forlornly over the gloomy sea.

In Maine, Homer became a painter so committed to his muse and his place that he created one painting after another of the timeless process of wave on rock. His need for people to narrate his stories diminished.

Sherry encourages visitors to pay attention to the details and variety within a single subject.

“I think many art historians and possibly also the public tend to think of these works as a unified whole,” she said. “This show will reveal the complexity of Homer’s work at Prouts Neck. He did a lot of seascapes while he was there, but I am finding myself amazed at the subtle variety of the seascapes. He makes every painting different and unique.

“That sense of diversity and range of approach to similar subject matter is what is going to be revelatory.”

SEVERAL MAJOR WORKS

The museum cast a wide net assembling this show. There are several major paintings on view, including “Fox Hunt,” on loan from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Homer painted it in 1893 on a canvas that’s almost 6 feet wide. It’s his largest painting, and considered by many to be one of the most important paintings in American history.

“Fox Hunt” depicts a flock of crows descending on a fox mired in deep snow. The Pennsylvania Academy bought it from Homer soon after he completed it. It’s a masterpiece because of its layered complexity, Sherry said. It’s beautifully designed, with sophisticated composition and precise technical execution.

It’s also thematically complicated. Homer thinks about nature in evolutionary terms, conjuring the Darwinian idea of survival of the fittest. We don’t know if the fox survives the hungry crows; Homer leaves to our imagination the cacophony of the attack that is moments away.

But the painting goes deeper than that. Pay attention to Homer’s signature. He makes his identification with the fox clear by altering his signature in the lower left corner to resemble the shape of the fox.

So important is this painting that the museum gives it an entire wall. It is the last painting in “Weatherbeaten,” cast against a gray wall. It is visible from throughout the gallery and will serve as a magnet, beckoning people slowly toward the exit for a long period of contemplation.

Securing “Fox Hunt” was no easy task, said Mark Bessire, the museum’s director. If fact, he added, none of the work came easily. Loans came from throughout the country, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and many others.

Several works reside in Maine. Some are from the PMA’s own collection, as well as at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville.

“Museums like their Homers, because people like to visit them. Museums do not like to take them off their walls. It is not good for business,” Bessire said.

A MILESTONE FOR THE MUSEUM

Thomas Denenberg, the PMA’s former chief curator, spent several years working on this exhibition before moving to Vermont for another job. He considers “Weatherbeaten” a crowning jewel in the museum’s history. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see those paintings all together,” he said.

John Wilmerding, a retired Princeton University art professor and Homer scholar, said “Weatherbeaten” will give people a better understanding of the importance of place in an artist’s creative process.

Homer had only to look out his window on Prout’s Neck to find his subject, or walk upstairs to his open-air piazza. The immediate physicality of his subject allowed him to pursue every detail.

Yes, there are a lot of paintings of waves crashing on rocks, Wilmerding said. But Homer’s pieces are so much more than that. There is tension and conflict, and that only becomes obvious with seeing the paintings up close as a cohesive body.

“These late-career paintings take you so far beyond picturesque descriptions,” he said. “You are left with the sheer sense of plastic paint, the physicality of the paint and the way he makes water. It’s not just liquid. It’s almost as if he understood the new physics. It was the molecular structure, that water could stand up to rocks.

“With this work, Homer began a new kind of realism. It was maybe based on observation, but he takes it well beyond, and makes it personal and cosmic.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be reached at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.