PORTLAND – Two elementary schools in Portland failed to meet targets for standardized tests for the second consecutive year in 2011, triggering a requirement for state-approved improvement plans and allowing parents to send their children to other schools.

The school district sent a letter last week to parents of students at the Hall and Presumpscot elementary schools, notifying them that the schools hadn’t met reading standards under the federal No Child Left Behind law. The law calls for all students to meet math and reading standards by 2014.

Only a few parents have requested transfers, said David Galin, the school district’s chief academic officer. Parents have until Aug. 31 to decide; school starts on Sept. 6.

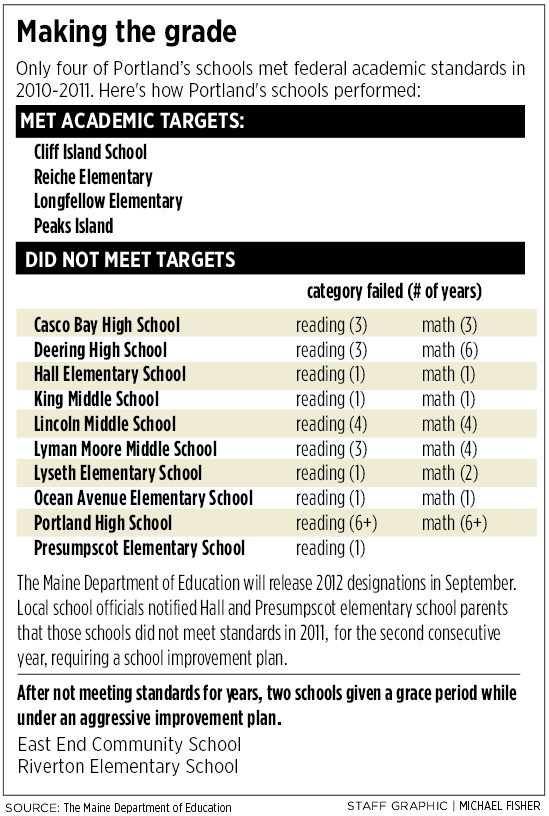

Only four of Portland’s 16 schools — 25 percent — met the standards in the 2010-11 academic year, the most recent year for which results are available. Statewide, 184 of the 608 public schools — 30 percent — met the standards.

The state will release the 2011-12 results in September, said David Connerty-Marin, spokesman for the Department of Education.

Portland and Deering high schools haven’t met the academic standards in more than six years. Casco Bay High School hasn’t met them in the last three years.

No Child Left Behind, signed into law in 2001 by President George W. Bush, envisioned all students achieving 100 percent proficiency in reading and math by 2014. The program, intended to increase accountability and education standards, measures success based on standardized tests.

The law has been criticized as overemphasizing tests and setting unrealistic expectations.

Last year, 75 percent of 3rd- through 8th-graders were expected to meet reading standards, and 70 percent had to meet math standards. For 11th-graders, the expectation was 78 percent in reading and 66 percent in math.

Those targets are set for schools as a whole and for eight subgroups: Asian/Pacific islander; Black/African American; Caucasian; Hispanic; American Indian/Native American; economically disadvantaged; students with disabilities; and students with limited English proficiency.

If one subgroup fails to meet targets, the whole school fails.

At Hall Elementary, the Black/African-American subgroup did not meet the reading standard.

Portland doesn’t report how many students make up any subgroup because that could identify individual students, said Principal Cynthia Remick. Subgroups must have at least 20 students to be counted.

Remick said it was difficult for her to specify which subgroup didn’t make the standard in her letter to parents, but federal law requires her to tell parents exactly where the school is not meeting standards.

“I know that can leave a bad taste in parents’ mouths because it has the impression of finger-pointing, which is not my intent,” she said.

At the Presumpscot school, two subgroups didn’t meet reading targets: Caucasians and students with disabilities. Principal Cynthia Loring could not be reached for comment.

Sarah Scaplen said she was surprised by the district’s letter because it didn’t mesh with her experience with the Presumpscot school. Her daughter, Hadley, did very well in reading in kindergarten, she said.

The family no longer lives in Presumpscot’s district, but choose to have the children stay in the school. Scaplen’s son, Damian Cobb, went there from kindergarten through fifth grade and is now going into the seventh grade.

“I’ve known all the teachers there for years. I want (Hadley) to have the same experience he did,” Scaplen said.

Krista Haapala, the mother of a student at Hall school, said Friday that she’s glad to know the school system is tracking performance, so it knows which students need help. She hopes the test results will serve as a catalyst for action.

“I hope parents would see that and say, ‘Gosh what can I do?’ instead of moving their kids to another place,” she said.

Connerty-Marin said the state receives about $1 million a year to help struggling schools pay for professional development. A short burst of funding was available through the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act of 2009, which provided about $13 million to improve struggling schools in Maine.

Portland’s Riverton Elementary and East End Community schools received three-year school improvement grants of $3.4 million and $2.7 million, respectively, to turn around students’ performance by replacing half of the faculty, among other steps. Last year, the schools met the standards.

Connerty-Marin said stimulus funds are no longer available, so districts will have fewer resources to help turn around their schools.

Remick, who worked on No Child Left Behind issues in Westbrook for eight years before becoming Hall’s principal, said the improvement plan requires the school to spend a certain amount on professional development, and to increase parents’ engagement.

“It’s more than just inviting parents to the school for just a fun activity, like a cookout,” she said. “It’s really getting parents engaged in what students are learning, so we have a strong home-school connection.”

Other components of the plan will be determined by a panel of administrators working with a Department of Education consultant, Remick said. Other programs could include before-, after- and summer-school programs, she said.

Remick said Westbrook began a literacy program during the summer, when many students fall behind. The program was “a huge success,” she said, with 95 percent of targeted students participating and 90 percent of them increasing their skills.

“Essentially, we eliminated that summer slide,” said Remick, indicating she will propose a similar program at Hall.

Galin said it is difficult to get off the list of failing schools, because the target gets higher each year.

From 2005 to 2008, the reading target for elementary students was only 50 percent proficiency, and the math target was 40 percent. Each target has increased incrementally since then, toward the 100 percent goal by 2014.

“It’s not that schools are doing worse,” Galin said. “The bar has been raised.

“We look at that as positive,” he said. “Any time student achievement is not where we want it to be, we know that professional learning for our staff is where we want to do improvement.”

Last year, President Obama announced a program that would give states more flexibility to meet No Child Left Behind standards, including allowing states to customize academic interventions for struggling students, granting greater flexibility in how federal funds can be used, and allowing schools to measure students’ growth through multiple measures, rather than just test scores.

As of February, 11 states had received waivers from No Child Left Behind and 26, along with Washington, D.C., had pending waiver applications before the U.S. Department of Education.

Connerty-Marin said Maine is working on a waiver application, with a Sept. 6 deadline. Instead of trying to meet the “arbitrary targets” established by federal law, the state would like to focus on students’ growth, he said.

“We’re looking to change the accountability system,” he said.

Staff Writer Ann S. Kim contributed to this story.

Staff Writer Randy Billings can be contacted at 791-6346 or at:

rbillings@mainetoday.com

Twitter: @randybillings

Send questions/comments to the editors.