Sometimes in Portland, we take our cultural amenities for granted.

We have so many to choose from – and so many new things to engage our imaginations – that we often overlook the treasures that have been here a long time and deserve our attention.

The Portland Observatory, for one. The Longfellow House is another example. The Victoria Mansion.

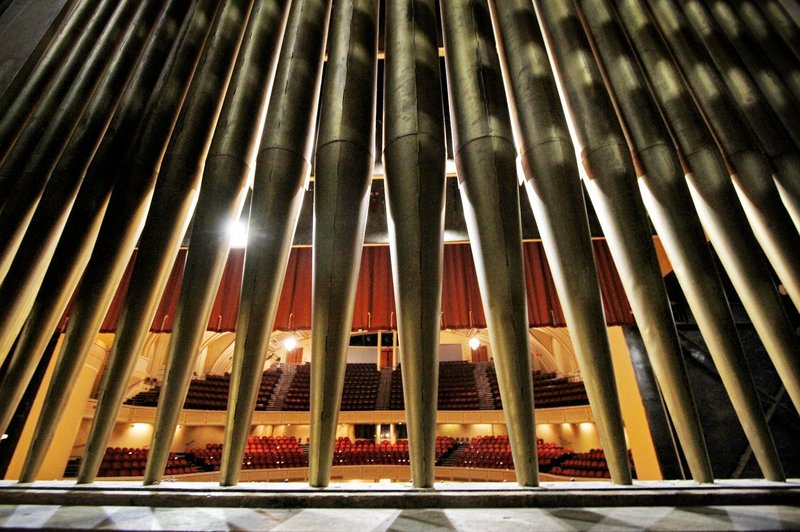

Tops on the list may well be the Kotzschmar Organ, the estimable king of instruments that resides within City Hall and gives Merrill Auditorium its brassy character.

The massive pipe organ, which turns 100 next week, will soon be disassembled, refurbished and rebuilt to its original luster as part of an ambitious $2.6 million restoration project.

But before the Kotzschmar goes silent, the Friends of the Kotzschmar Organ will celebrate the instrument’s majesty and historical significance with a Centennial Festival.

It begins Friday and continues through Aug. 22, the day the organ turns 100.

The festival will feature performances by almost a dozen local, national and international organists. There will be master classes, workshops, lectures and many opportunities for people to learn more about the instrument as well as the plan to refurbish it.

Most of the centennial activities will be centered at Merrill and the official festival hotel, the Holiday Inn by the Bay.

But organs at churches in town – St. Luke’s and Williston Immanuel United – will also host performances.

The Kotzschmar will go silent following a gala concert on Aug. 22. The next day, a team from organ builders Foley-Baker Inc. of Tolland, Conn., will erect rigging and begin disassembling the organ’s 6,852 pipes and all of its mechanics.

It will take up to five weeks to remove the organ and pack it up, and up to 18 months to refurbish and rebuild it.

A new wind chest will be constructed, and all the pipes, leathers, mechanisms and electrical hooks-ups will be rebuilt, cleaned and rewired.

The result, said Ray Cornils, Portland’s municipal organist, will be a better-sounding, more responsive and healthier organ.

“Its lungs are leaking. You hear that with the hiss; it does not always have the proper air pressure it should have. You notice it especially in the bass and tenor pipes,” says Cornils, who has played the Kotzschmar for 22 years and knows it as well as anyone.

“The goal is that you will not hear the hiss. You will hear a clarity of the tenor and bass lines and a presence that is not there now. It’s just not in good voice, and you do not use certain notes. There are many, many ways musicians can mask the flaws. But in the future, you will hear a wider variety of sounds and a greater freedom of the organist.”

The Kotzschmar is renowned. Among those who care about such things, Portland’s famous organ is as much a draw as the National Baseball Hall of Fame is to baseball fans or the Metropolitan Opera to opera fans.

“Those for whom the organ is an important and interesting diversion are, and have been for 100 years, aware of the Kotzschmar,” said Michael Barone, host of American Public Media’s radio program “Pipe Dreams.”

Barone often features music performed on the Kotzschmar on his nationally syndicated radio show, and will emcee the centennial celebration in Portland.

“Even if they haven’t been able to get to hear it very often, they have followed its progress and applauded its successes. It is very noteworthy,” Barone said.

Put another way: If ever we were going to pay attention to the Kotzschmar, these next 11 days offer us the best opportunity.

Among the highlights:

• From 9:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Saturday, Barone will host “Performathon Maine,” featuring Maine organists and tours of the organ.

• At 10:30 a.m. Saturday and again at 10:30 a.m. Aug. 20, Mike Foley of Foley-Baker will discuss details of the restoration project.

• The Gala Concert, featuring Cornils and Peter Richard Conte, organist of the Wanamaker Organ in Philadelphia, begins at 8 p.m. Aug. 22.

“We really want the community to celebrate with us,” said Kathleen Grammer, president of the Friends of the Kotzschmar Organ. “I think the organ represents an historical and a musical legacy in the city. I believe if people don’t know anything about it, now is the time to join us in celebrating and learning about this legacy.”

NAMED FOR POPULAR ORGANIST

The Austin Organ Co. of Hartford, Conn., built the Kotzschmar in 1912. At the time of its construction, it was the second largest organ in the world.

The organ was a gift from Cyrus Curtis, who grew up in Portland and made his fortune in the publishing business. Among other things, he published the Ladies’ Home Journal and the Saturday Evening Post, as well as several large newspapers.

Curtis named the organ in honor of Hermann Kotzschmar, a German native who came to Portland in 1849 and lived here until he died in 1908.

During his first year in Portland, Kotzschmar lived with Curtis’ parents. He might have stayed with them longer, but he had to find his own housing when young Cyrus was born in June 1850.

Curtis’ parents named their boy in honor of their musical friend. He was christened Cyrus Hermann Kotzschmar Curtis.

Kotzschmar was wildly popular. He was one of Portland’s earliest arts advocates, and is credited with helping transform the city from a rough outpost into a cultural destination. He was a popular music teacher, and became Maine’s preeminent musician.

When Portland’s former city hall burned in 1908, city planners immediately decided to rebuild, with a grand auditorium that included an organ. Curtis, then living in Pennsylvania with enormous wealth, offered to fund the organ on the condition that it be named in honor of Kotzschmar, who had died that same year.

And so became the famous organ. It was dedicated on Aug. 22, 1912.

At the time, the Kotzschmar was the first municipal organ built in the United States, and it set a trend.

“Civic leaders saw the pipe organ as representing the epitome of musical culture,” Barone said. “It was thought that cities ought to have them.”

Portland was the first, and remains one of the last. Almost all of the municipal organs have been lost. The Kotzschmar is one of only two municipal organs still owned by a city; the other is in San Diego.

Barone is impressed with Portland’s commitment to the organ. The City Council barely hesitated when asked to help fund the organ’s restoration. With a unanimous vote, it approved up to $1.25 million in bonds to help cover the cost.

The Friends of the Kotzschmar Organ will raise the rest, and Grammer said the organization is close to reaching its $2.6 million goal (including the $1.25 million from the city), to pay for the restoration. The overall fundraising goal is $4 million, which will include an endowment.

A COLORFUL INSTRUMENT

As municipal organist, Cornils also sits in a unique position. Portland established the municipal organist post in 1912, and it remained until 1981, when it was eliminated because of budget concerns.

That’s when the Friends of the Kotzschmar Organ formed, to provide funding for the organist as well as money for the upkeep of the organ.

To date, there have been 10 municipal organists in Portland.

“It’s a great honor,” said Cornils. “It’s an instrument that really allows you to be wildly expressive, in that it’s able to bring out the personality of the organist and the musicians as they conceptualize the music. It has a wide palette of color. You are given a broad spectrum to be creative.”

He describes the process of playing the Kotzschmar as “very smooth and almost silken. It challenges you to find the essence of the music at a greater level than many other smaller instruments might do.”

After the restoration, the organ will once again deliver its full power.

“It’s kind of nice that the heritage of the organ still resonates with the population today. What was, remains important now,” Barone said. “It has had its advocates who have been sowing positive seeds.

“Because of that, Portland can boast something that most cities don’t have: A major concert hall with a major pipe organ.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.