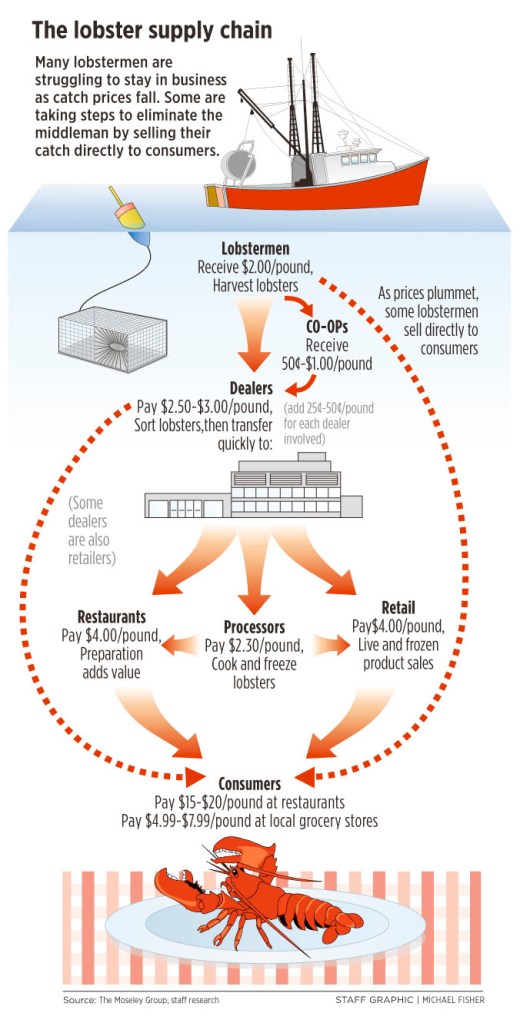

Once caught, a lobster can change hands five to seven times before it reaches a diner’s plate.

Lobstermen this summer are getting paid as little as $2 to $2.50 a pound for their catch — the lowest level in 30 years — but the price escalates to $17 a pound or higher by the time a customer orders a lobster in a restaurant.

“It depends on whose plate it’s going to and where that plate is,” said Stephanie Nadeau, owner of The Lobster Co., a lobster dealer in Kennebunkport. “Is it a live lobster or a frozen lobster product?”

The economics of the lobster industry have come into focus in the past week, as Canadian lobstermen set up blockades to prevent Maine lobster from being shipped to New Brunswick processors. At the heart of the matter are the low prices that lobsters have commanded this year. With processors in New Brunswick paying less for Maine-caught lobsters, Canadian lobstermen say they can’t compete — and that the situation is threatening their livelihoods.

Maine, which landed 105 million pounds last year, is the nation’s largest lobster producer. The state catches 75 percent to 80 percent of the American lobsters — Homarus americanus — caught in the United States, according to the Lobster Institute at the University of Maine.

Last year’s catch in Maine was valued at more than $330 million at wholesale prices. But lobster’s total economic impact on the state is estimated to be as much as $1.7 billion. That’s because for every dollar paid to a lobsterman for a lobster, $3 to $5 is generated for related businesses such as dealers, processors, restaurants, stores, marina and bait suppliers, the Lobster Institute said.

Add in Canada — which itself catches more than 120 million pounds a year — and the numbers swell even more. The Lobster Institute estimates the lobster industry accounts for more than $4 billion of activity in the United States and Canada.

In other words, an enormous, multibillion-dollar economy is built around a creature that is currently selling for $2 a pound at the dock. Where does all that money come from?

$2 LOBSTER SOLD, AND SOLD AGAIN

Once a lobsterman comes into port and unloads a harvest, the lobsters are bought by a co-op or dealer. A lobsterman gets paid $2 to $2.50 a pound at current prices. More than one dealer could be involved in a trade, which adds 25 cents to 50 cents a pound per transaction.

A crate of lobster averages 90 pounds of water-soaked lobsters. As the water leaks out, that weight shrinks to about 87 pounds by the time a dealer gets the crate to a facility to sort the lobsters for quality — so a dealer paid for 90 pounds of lobster but got only 87 pounds. Of that, some might be dead or broken, which shrinks the value further, dealers say.

Dealers then sort the lobsters for quality and hardness. The strongest lobsters get sent to the “live” market — retail stores and restaurants. The “mush monsters” or “jelly rolls” — nicknames for the softest of the softshells — go to processing plants. There, the lobsters are broken apart, cleaned, cooked or frozen, for everything from lobster tail at a Red Lobster to meat used in lobster ravioli in a grocery store freezer section.

Of an average order of 120 crates at 90 pounds each, only 17 crates might be usable for the live lobster market, said Kerin Resch, owner of Eastern Traders in Nobleboro. The rest goes to processors.

“There’s losses all along the way,” Resch said. “We’re all in this together — the quality issues, the financial hardships. The price of fuel and bait is up. Fuel for my trucks is up.”

This year, Maine has had a bumper crop of lobster that it can’t handle in its three processing plants.

“There’s way more supply than consumers have the appetite for,” Resch said. “The guy in Iowa who is watching his cornfield wither is not going to go out to a Red Lobster to celebrate with lobster. There’s only so much lobster people choose to eat.”

PROCESSORS PAY LESS

While some lobster was rotting because there was no capacity at Maine’s three processing plants and Canadian processors were temporarily blocked from taking Maine lobster, part of the problem was eased through an unofficial, unspoken decision by lobstermen not to fish for part of July, said Resch. That eased a backlog into the processing plants.

“The tie-up averted a huge disaster,” Resch said.

As much as lobstermen complain that they get too low a price at the docks, dealers complain that the quality of lobsters this year is bad because of the warmer water temperature — which softens shells — and that too much supply is ending up in processing plants, which pay less than the live market.

“I lose money on a lobster that goes to a processing plant. The plant might pay $2.30 a pound, and I paid $2.50 or $3 a pound to get them from a co-op or other dealer,” Nadeau said. “I lose 25 cents to 40 cents (per pound) or more on the bad ones, so I have to build that into the price of the good ones I sell to offset the loss.”

Seventy-five percent of the total catch in the United States and Canada is processed, and Canada controls more than 90 percent of the processing market, according to the Lobster Institute. Canada has 32 processing plants; Maine has three major plants. Maine has relied on Canadian processing plants for more than 60 years, because the state lacks enough plants to handle the catch.

Maine has lost two plants in the past year. Live Lobster, a processing plant in Gouldsboro, closed earlier this year. Portland Shellfish Co.’s processing facility was closed in April by federal regulators for “numerous violations” of federal laws and health regulations.

That left three major processing plants in Maine — Cozy Harbor Seafood in Portland, Shucks Maine Lobster, and Linda Bean’s Maine Lobster in Rockland. Smaller facilities such as Maine Coast Shellfish in York exist and Sea Hag Seafood is trying to open its doors in Tenants Harbor.

The closure of Portland Shellfish was a hit to the industry, dealers said. With fewer places to ship lobster and processors with less competition, other processors started paying lower prices.

“It probably cost everyone 25 cents a pound when they went out of business,” Nadeau said.

$60 WHITE TABLECLOTH DINNER

For a lobster to get to a fine restaurant, it has to be a higher-quality, harder-shelled lobster.

For Hancock County lobstermen to supply 2,000 pounds of high-quality lobster for a cruise ship Wednesday, they had to catch 8,000 pounds of lobster. The remaining 6,000 pounds went to lobster shacks or processors, said John Sackton, editor and publisher of Seafood.com, a website that covers the industry.

For restaurants to keep food at 35 percent of total costs, they have to charge more than $14 a pound for lobster if they pay $5 a pound from a dealer. They usually charge more — as much as $17 or $20 a pound — since seafood is fragile and has a short shelf-life. Even a simple lobster roll at a roadside stand involves the cost of picking and cleaning the lobster.

“A lobster travels in an ever-increasing ring,” Bean said. “People get paid for each step along the way and we have to account for the losses. That’s how a lobster roll costs $17 and a white tablecloth, fancy lobster dinner costs $60 in a big city.”

Staff Writer Jessica Hall can be contacted at 791-6316 or at:

jhall@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.