An insect that threatens Maine’s ash trees has spread into central Connecticut, as it steadily makes its way toward northern New England.

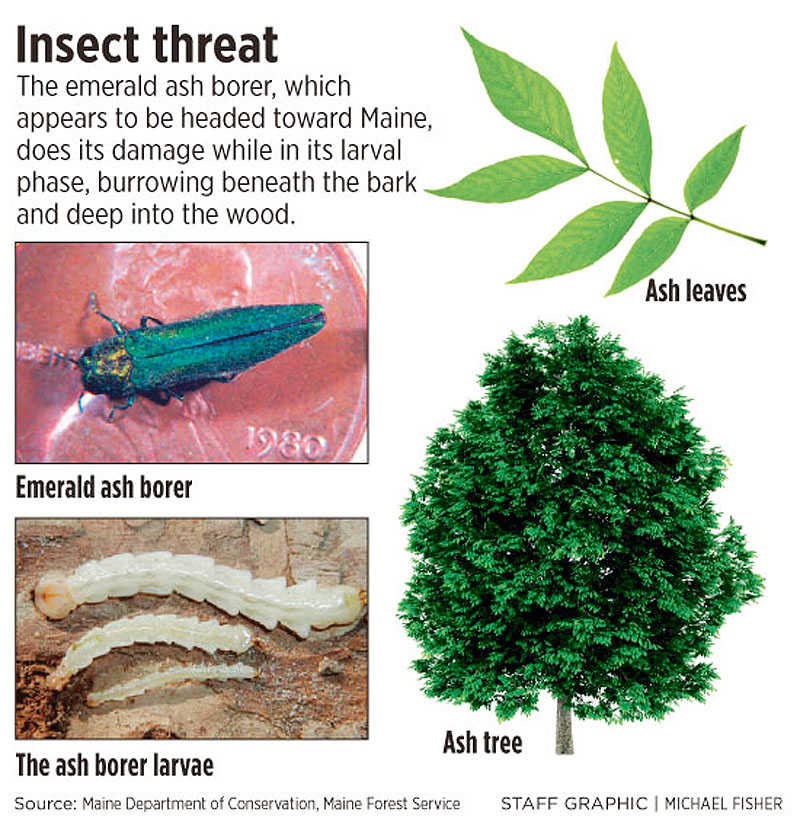

The emerald ash borer, an invasive species of metallic-green beetle, kills in its larval stage by eating into the wood beneath the bark of ash trees and effectively girdling them, cutting off the flow of vital nutrients.

“It could be here,” said Charlene Donahue, forest entomologist with the Maine Forest Service. “We don’t feel we have much time at all.”

Thought to have made its way into North America on wood-packing products from Asia, the highly destructive beetle was first discovered 10 years ago in the Midwest and has been moving inexorably east and somewhat south in the United States and into parts of Canada, decimating millions of ash trees in its path, said Maine state entomologist Dave Struble.

Officials believe the beetle spread in the states in firewood transported from state to state. It has jumped the Hudson River, appearing along the Massachusetts border and most recently near Prospect, Conn.

That means it now is doing its damage within a half-day’s drive from Maine — alarming because many summer day-trippers and campers come here from nearby New England states and, as part of their stays, enjoy campfires. Consequently, residents and visitors alike have been asked not to transport firewood over state lines.

Last summer, state forest service officials made random checks of cars coming into Maine to make sure no firewood slipped through, partly to monitor the pest but also to educate people. This year, traps and biological methods are being used to detect the beetles’ arrival.

“Sooner or later, it’s going to get here,” Struble said. “It’s certainly not a great big shock; it’s disheartening, though. The whole situation concerns me a lot.”

About 6.7 million cords of ash wood are harvested in Maine each year, with a value of about $140 million annually, said Kenneth Lautsen, biometrician for the Maine Forest Service.

Those statistics reflect that ash trees do not constitute “a big component of our forests here in Maine,” he said, but their loss would have a significant impact on forests and on industries which use the tree’s wood in products, including furniture, that require strength and flexibility.

And “it’s not just industry” that would be hurt, Donahue said. Beyond these threats lies perhaps the most crucial consideration of all — “the way everything works together in an ecosystem.”

When the trees are debilitated or killed, there’s a ripple effect: Birds which might nest in the branches must find other safe haven, and wildlife which might seek shelter or food there must look elsewhere.

Take away the ash, and you remove the essential biodiversity of the forest in which it once thrived. “If we only end up with red maple,” Donahue said, “there won’t be everything you need to support the ecosystem.”

The fruit of the ash provides food for quail, wild turkey, grouse, finches, grosbeaks and other songbirds, while young twigs and leaves provide vegetation on which deer and moose browse, according to material from the University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

“If (ash) follows the same pattern as in the Midwest, we will lose most” of the state’s ash trees, Struble said. The result “would not be an ecological desert,” he said, “but completely losing anything slims down your biodiversity, your resiliency. We’d be biologically the poorer.”

But the imminent risk to ash trees, which typically grow to 70 or 80 feet tall, represents more than a loss to industry or an ecological concern about diminishing diversity among all the life of the northern woods; it constitutes a cultural threat, too.

“It is very, very important,” Lautsen said, “to Native Americans.”

For the Wabanaki nation, the tree plays a crucial part in the creation story: The first Indians emerged from the bark of these trees.

Today, brown ash is still used by several Indian tribes to make their traditional functional, artistic baskets.

Comparing the potential devastation of ash trees to the near-eradication by beetle-borne fungus (Dutch elm disease) of the stately elms that lined many city streets in the 1950s, Struble said that the efforts to control the spread of the emerald ash beetle could not keep pace with the speed of its movement or destruction.

In the case of infestations of ash borers, Donahue said, affected trees “have to be taken down before they die.”

As the tree is stripped from the top down, and the borer completes its life cycle, leaving behind a new generation to take over, the tree — a dry wood, even when healthy — dries out so completely that “when you cut it down, it smashes into a million pieces and creates a debris field. It makes it very expensive” to clean up.

“Towns aren’t prepared to do” the tree removal, she said, estimating the task could run at least $200 a tree. Communities in the state have not budgeted for that expense, which makes prevention and containment even more important.

“People have to keep their eyes out” for signs of the beetle — if not the bug itself, then indications such as the vulnerable tree’s top branches dying.

This year, nearly 1,000 purple traps that “look like a big box kite,” Struble said, have been spread around the state to capture the beetles should they show up.

Additionally, biosurveillance, using one living organism to monitor for another, helps with detection and control.

A native, ground-nesting and non-stinging wasp, Cerceris fumipennis, has proven efficient as a survey tool, because it preys on the emerald ash borer, paralyzing it and using the beetle in nesting.

“They’re far more effective at finding these beetles than we are,” Struble said. So, human monitors watch the nests.

Finally, a number of volunteers around Maine are sacrificing one of their own ash trees, girdling them to stress the trees and make them more vulnerable to the pest. In the fall, these trees will be cut down and checked for signs of the beetles and larvae.

The borer does its most serious damage in the larval stage, burrowing not just beneath the bark but into the deeper layers of the tree’s wood.

Until a control method is found, entomologists and horticulturists have little in their arsenal to fight the pest, Struble acknowledged, except “to contain it as long as you can.”

Staff Writer North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6305 or at

ncairn@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.