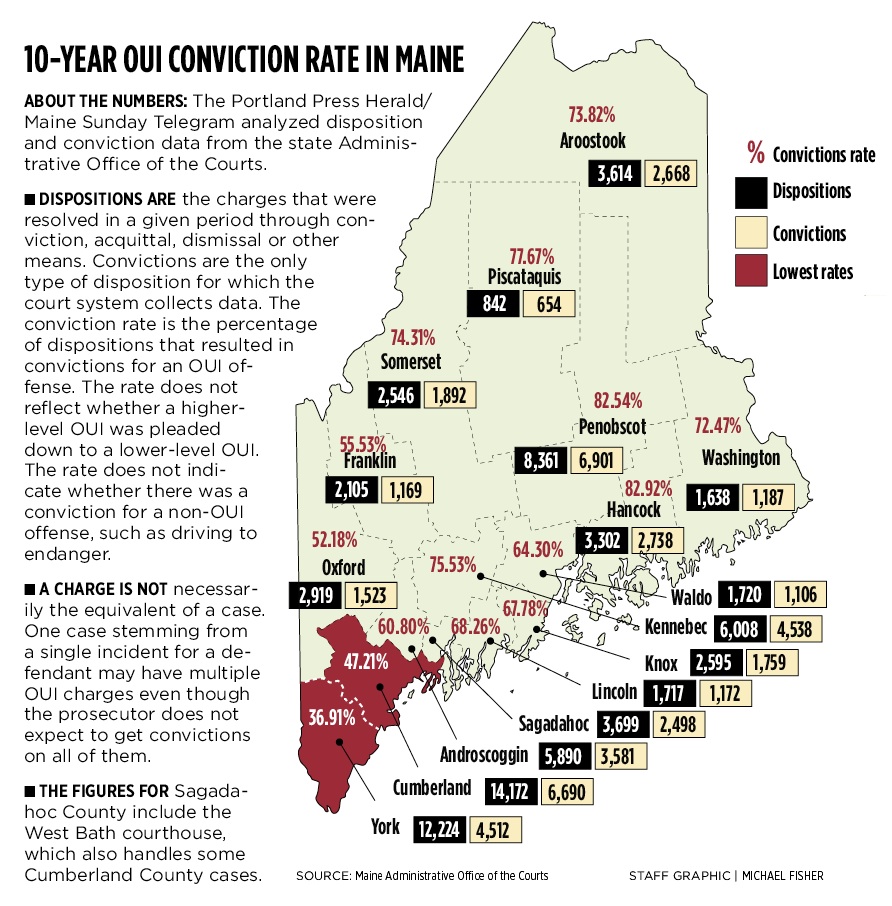

Conviction rates for charges of operating under the influence vary widely from county to county in Maine, with the 10-year average ranging from a low of 37 percent in York County to a high of 83 percent in Hancock and Penobscot counties, according to an analysis by The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

The contrast is even starker in individual years. Ninety-four percent of OUI charges resolved in Hancock County in 2010 were convictions, compared with 32 percent in York County that same year.

The newspapers analyzed 10 years of data provided by the state Administrative Office of the Courts. The analysis compared the number of dispositions — that is, charges that were resolved through conviction, acquittal, dismissal or other means — to the number of convictions by year and over the period of 2002 to 2011.

It was not clear whether any organization tracks national conviction rates for impaired driving, so it’s difficult to assess how Maine stacks up against other states.

Prosecutors, defense attorneys and law enforcement officers cite district attorneys’ policies, case volumes and the resources of the judiciary in a particular location as some of the reasons behind the wide discrepancies.

Some district attorneys have a policy against pleading down OUI offenses to driving to endanger — a practice that is routine in other counties.

R. Christopher Almy, the district attorney of Penobscot and Piscataquis counties, said his office’s policy against reducing an OUI to driving to endanger lets police officers know that the prosecutor will stand behind them and also lets people know that there is no special treatment.

“If you start dropping these to driving to endanger, the question is, ‘Who gets the break and who doesn’t get the break?’ ” he said. “It may appear that people with high-priced lawyers get a break or people with important jobs get a break or there’s some special reason. We just flat-out say no.”

In Cumberland County, which had a 10-year conviction rate of 47 percent, District Attorney Stephanie Anderson has a policy that defendants are offered the chance to plead guilty to driving to endanger when it’s a first offense and the breath test indicates a .08 or .09 blood alcohol content. She said that because of the breath test’s margin of error in measuring blood alcohol content, it may not be possible to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone is over the legal limit of .08.

With about 12,000 cases of all types coming through her office annually, Anderson said she values tough screening of cases and has a goal of getting rid of half the cases at the arraignment stage.

Anderson said that in an underresourced system — her next trial list has 78 cases, but she says there’s time to try only about six — she has to balance OUIs with other crimes such as armed robbery and gross sexual assault.

“I think it’s better to get something rather than nothing at all,” she said.

Cumberland County Sheriff Kevin Joyce said drop-downs of OUIs reflect the reality of limited court resources.

“I think it’s a realistic approach. I don’t know if it’s an OK approach. It is what it is,” he said.

York County District Attorney Kathryn Slattery said she does not have a set policy about dropping down an OUI charge. Prosecutors consider each case on an individual basis and may weigh factors including the defendant’s attitude, the details of the incident and whether there’s a substance abuse issue that can be addressed, she said.

“I think that as a general philosophy, I and all the people who work here do listen to circumstances particular to a defendant. There are some times it doesn’t matter, and there are other times when it does,” Slattery said.

Geoffrey Rushlau, district attorney for Sagadahoc, Lincoln, Knox and Waldo counties, believes that rigid prosecution policies force prosecutors to ignore the individual strengths and weaknesses of cases. While he doesn’t have a set policy, Rushlau said he tries to take an aggressive approach. His counties have 10-year conviction rates ranging from 64 to 68 percent.

“We have fewer OUI cases. I think that means we can give them more focused attention. We have a tendency, if a case has some defects in it, we try to resolve those defects,” he said.

The number of charges resolved in a particular county also range widely. Cumberland had the most for the 10-year period with 14,172 and for a single year, 1,667 in 2002. Piscataquis had the fewest over the 10 years, with 842, and the lowest number for a given year, 58 in 2011.

In high-volume courthouses, the system depends on plea negotiations, said Ed Folsom, author of the book “Maine OUI Law” and a Saco-based criminal defense lawyer.

“If the cases aren’t getting moved, the system just grinds to a halt,” he said.

Darrick Banda, a former assistant district attorney in the Kennebec-Somerset prosecutorial district, said that that office is among those with a no-negotiation policy. He said such offices are more likely to screen out cases with low breath-test levels.

“When you screen them out, the case is dead — done. The person will never be prosecuted for anything,” said Banda, who is running for district attorney in those counties.

But Carletta Bassano, district attorney of Hancock and Washington counties, said many of her .08 and .09 cases do go to trial. Her office’s policy is to not drop those cases down to driving to endanger.

“I’ve gone to enough roadside crashes where someone has died, where someone’s been drinking and driving,” she said.

Prosecutors in Aroostook County do not routinely drop an OUI to driving to endanger, according to District Attorney Todd Collins. The 10-year rate for the county was 74 percent.

“We do prosecute .08 and .10 OUI cases. We will take OUI cases to trial, where a defendant will sometimes be acquitted by a jury. When we do reduce or drop OUI charges it is because there is a legal or factual impediment to a successful prosecution,” he wrote in an email message.

Bangor-based Wayne Foote is among the criminal defense attorneys who said no-negotiation policies waste taxpayer money.

“You think of the cost of a jury trial,” said Foote, whose practice focuses on OUI cases. “You bring in the jurors. You bring in a judge. You have a prosecutor. You often have a court-appointed defense lawyer. You have a clerk and you have a court reporter.”

He noted that a defendant initially charged with OUI who is convicted of driving to endanger still faces penalties — a $575 fine, compared to $500 for the vast majority of OUI cases, and a court-ordered suspension of at least 30 days — as well as the likelihood of an administrative license suspension of 90 days through the Bureau of Motor Vehicles.

Lt. Louis Nyitray of the Maine State Police has worked in different prosecutorial districts. Currently based in Alfred, Nyitray said troopers do see cases dismissed for unexplained reasons.

“That does provide a level of frustration to the men and women of the police forces — state, local and the county — because we’re out there taking these people off the road and for whatever reason, they’re not prosecuted.”

Staff Writer Ann S. Kim can be contacted at 791-6383 or at:

akim@pressherald.com

Twitter: AnnKimPPH

Send questions/comments to the editors.