When Kevin Salatino tells people about the new William Wegman exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick, he often gets a blank stare in return.

When he refers to Wegman as “the dog guy,” people understand the reference immediately.

Salatino and his staff at the Bowdoin museum aim to expand people’s knowledge of Wegman and the span of his work in the just-opened exhibition, “William Wegman: Hello Nature.” On view through Oct. 21, it includes more than 100 paintings, photographs, drawings and videos that Wegman has created over the past 30 years.

Yes, the exhibition features a healthy sampling of Wegman’s widely known photographs of his Weimaraner dogs in unlikely poses. But they represent just a small slice of the work that is in this show.

“We want people to know what they are going to see,” Salatino said, “but we also want to surprise them.”

As much as this exhibition is about Wegman and his remarkable dexterity as an artist, it is about his relationship with Maine. Wegman, 68, lives seasonally in Rangeley. He’s been coming to Maine since he was 14.

The first time he came to Maine, he drove up with a couple of buddies, one of whom had just received his driver’s license. They lived in rural western Massachusetts, and were crazy about fishing.

“We read about the brook trout in the Rangeley area, and we had to experience it for ourselves,” Wegman recalled during a recent interview at the Bowdoin museum.

As luck would have it, they had car troubles and were stranded. Bud Russell, a local legend in the Rangeley area and owner of some of the finest rental camps on Kennebago Lake, took the boys in. He not only arranged for the car to be fixed, but he gave the boys a place to stay for a week.

“We were the toast of the town,” Wegman said. “Here we were, three teenagers from miles away, coming to Maine to fish.”

And so began Wegman’s love affair with Maine. As he grew older, he kept coming back. He rented places for years, and in 1979 finally bought his own camp. He and his family now spend as much time as possible at their camp on Loon Lake. The rest of the year, they live in New York.

Maine — and by extension, nature — has played a key role in Wegman’s work, and served as a key source of inspiration.

Not too long before he bought his own camp, Wegman acquired his first Weimaraner and named it Man Ray, in honor of the artist. The dog was much happier in Maine than elsewhere, so Wegman spent as much time here as he could.

Soon after, he got another dog, which had puppies. Before long, he was making goofy photos of his dogs, which became enormously popular. So popular that in 1982, the Village Voice named Man Ray “Man of the Year.”

Wegman became an international art star. He shot most of the best-known of those images in Maine.

But as Salatino is quick to point out, “Hello Nature” is not about Wegman’s love affair with dogs. It is about his love affair with Maine and its influence on his art in a broad sense.

Taken together, the work in the exhibition suggests that Wegman is every bit the landscape artist as any of the best-known painters who have inhabited this state over the past century or more, including Edward Hopper, whose Maine-centered work was the subject of a Bowdoin museum exhibition last summer.

The Wegman show follows a similar theme: An internationally known artist whose works transcends Maine but is directly and deeply influenced by the state. “Once again, we see Maine serving as an extraordinary catalyst for an important American artist,” Salatino said.

This is the first time a museum has focused on the role of the natural world in Wegman’s work. As part of the exhibition, Wegman worked closely with the museum to produce a catalog, which complements the exhibition. Design themes that appear in the catalog repeat themselves throughout the museum installation.

The exhibition itself almost feels like a 3-D version of the catalog — one informs the other, and both elements form equal parts of a larger puzzle. Both feel playful and witty, and full of humor.

That humor manifests itself in the dog photos, and shows up elsewhere as well.

One piece — a simple pencil drawing — begins with a horizon line intersected by two arrows. One arrow begins with a rudimentary, elementary-school style drawing of a sun: A circle with rays. Within the circle, Wegman writes the word, “yellow.” The other arrow begins under the word “blue,” which represents the sky. Both arrows terminate below the horizon, deep within the earth, which is represented by the word “green.”

Wegman sums it up thusly: “landscape color chart.”

Simple. Silly. Funny.

A large portion of the show includes excerpts from Wegman’s illustrated nature books, which compile drawings, collages, photographs and snippets of his writing. The books evoke a 1950s-era Boys Life motif with sketches of wildlife, whimsical outdoor scenes and silly illustrated camp recipes.

Try this one out on your next outing: Cinnamon Teal Duck Cake, with 1¾ teal ducks, 2½ cups cinnamon and 5 chopped nuts. Bake until done, and cut into squares.

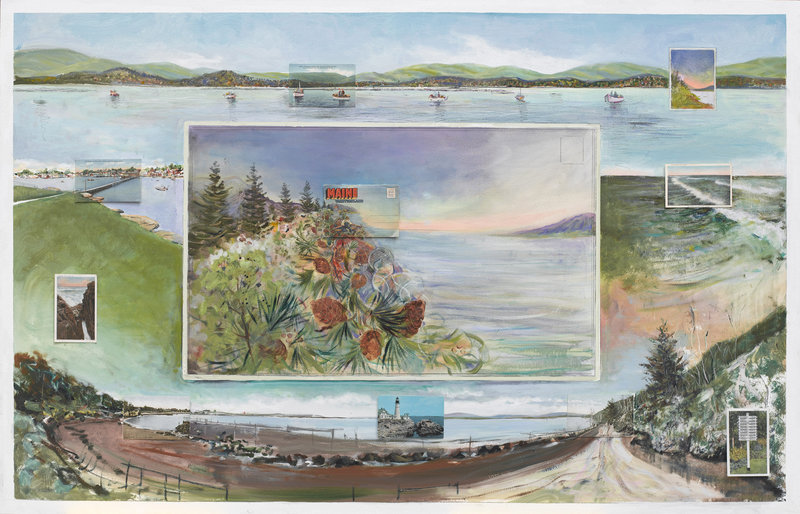

Wegman also includes a number of his postcard paintings. He begins them with postcards, usually of outdoor scenes in Maine, and extends the scene beyond the boundary of the postcard.

Wegman shows some of this work now and again, and just closed a show of his postcard paintings in New York. But most museums and galleries are interested in his dogs. The opportunity to show so much of this other work is a real treat, he said.

He called this lesser-known body of work his underdog.

“I don’t need it or quest for it,” he said, “but I like to be able to do it without a lot of attention. It’s almost a luxury to not push it. The dogs are just so overexposed.

“But I’m really not a dog guy. They’re just a part of it.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.