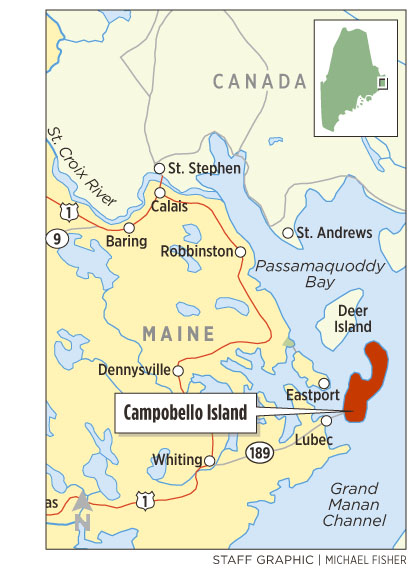

CAMPOBELLO ISLAND, New Brunswick — For the 925 year-round residents of this Canadian island a few hundred yards east of Lubec, Maine, accessing the Canadian mainland is something of a trick.

For 10 months a year, you really can’t get there from here without a valid passport, two border inspections and having your vehicle and its occupants pass between radiation-detecting pylons.

The 10-mile-long island is connected to Maine by a short bridge over the Lubec Narrows, but miles of cold, deep, tide-swept ocean separate it from the rest of New Brunswick. In July and August, islanders can drive down a gravel beach and onto a tiny car ferry, ride to Deer Island, drive eight miles and wait for a second ferry link to the mainland.

Any other time, they’re out of luck, which presents a challenge since the island has few jobs or retail shops and no bank, gas station or hospital. Electricians, heating oil deliveries and even the mail have to make a one-and-a-half-hour trip through Maine and U.S. Customs to get here.

This quirk of geography was once a minor inconvenience. For generations, people in these parts had paid little thought to the border, traversing it to shop, date, marry and deliver their babies. Thousands of people in easternmost Maine and southwestern New Brunswick are dual citizens on account of birth or marriage, including New Brunswick Premier David Alward (born in Massachusetts) and a quarter of Campobello’s residents (born at the hospital in Machias or with the midwife in Lubec).

“Maritime commerce and fisheries were very much a part of this area, so people crossed the border all the time out of necessity and habit,” says Hugh French, director of the Tides Institute and Museum of Art in Eastport, a town whose now-defunct sardine plants once attracted workers from Campobello and other nearby Canadian islands. “Family ties in this region are just very, very strong.”

The 9/11 attacks and the subsequent hardening of the border have complicated life here. Locals used to being waved through U.S. Customs found themselves subject to searches. Cancer patients returning to Campobello from chemotherapy treatments in Saint John have been detained after setting off radiation detectors at the Calais border crossing. Since 2008, those without passports haven’t been able to enter the United States at all.

Now there’s a new challenge: the U.S. Internal Revenue Service.

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act – a new law aimed at catching tax evaders with offshore bank accounts – has caught the region’s many dual citizens in its net. The law enforces requirements that any U.S. citizen residing abroad file an annual tax return, and compels foreign banks to disclose information on such people with more than $50,000 in assets.

“This is a very unfortunate decision that was made in Washington and frankly lacks any common sense,” says John Williamson of St. Stephen, across the border from Calais, who represents this part of New Brunswick in the Canadian Parliament. “Canada is not a tax haven – we have a high tax burden in this country. This is taking a sledgehammer to deal with a very small problem, and needlessly complicates the lives of ordinary, hardworking citizens.”

When news of the changes broke last summer, Calais tax preparer Tammi J. Smith says her office “started getting bombarded with calls.”

“There were people who were afraid to come over to (Maine to) shop if they had a Canadian passport that lists the United States as their place of birth,” she recalls. “The worry is that they will get questioned if Homeland Security gets involved in policing these things.”

The U.S Embassy in Ottawa referred queries to the IRS, where Commissioner Douglas Schulmann has said that the goal was “to get people back into the U.S. tax system,” therefore “bringing revenue into the U.S. Treasury and turning the tide against offshore tax evasion.”

“I don’t know if this is being done for money laundering or because Washington is in such financial distress that they have gotten desperate for revenue,” says a skeptical Williamson. “There are elderly people in my (electoral district) that are not going to take the risk to cross the border.”

Even on isolated Campobello, some people have refused to get a passport or to cross into the U.S.

“They get someone else to do your stuff if you need stuff done over there,” says Theresa Mitchell, a seventh-generation island resident who is herself a dual citizen because both her parents were delivered in Maine. “They say they’re not going to spend the money or have anything to do with it. They bite their nose off in spite of their face, so to speak.”

Tax experts say that beyond the hassle and expense of filing additional tax returns, Canadians shouldn’t fear that they will owe Uncle Sam a huge tax bill. Tax treaties ensure that the same income isn’t taxed twice.

“Normally the Canadian tax rates are higher because we have fewer deductions than the U.S. does,” says Sean McGroarty, a partner at Deloitte in Toronto, who notes that even where exceptions exist and a tax must be paid, it can generally be taken as a carryover credit on one’s Canadian taxes.

“Conceptually, the two systems have been designed via the treaty to work together so that you’re not in a situation of having to pay taxes to both countries on the same income,” he adds.

Last week, the IRS announced it has decided to allow many dual citizens considered to be “low compliance risks” to catch up on their tax filings “without facing penalties or additional enforcement action.”

For Campobello, the tax law added another stress to a community already coping with border issues and the long-term decline of what had been a fisheries-based economy. The island’s year-round population has already fallen by one-third since 9/11, in part because border complications make it more difficult to attract new year-round residents to replace those who move away or die.

“For certain people, it’s bad enough that your own government knows every dime you have, but to have a foreign country do so as well is a little bit unnerving for sure,” says island mayor Stephen Smart. “The fear was quite large, but fortunately there haven’t been any serious problems so far.”

There have long been calls for New Brunswick to provide year-round ferry service to the island, but these have been stymied by the estimated $40 million price tag of setting up such a system.

“There is not a whole lot of money kicking around to fund that,” says island fisherman Curtis Malloch, the island’s representative to the provincial legislature, who points to the province’s massive debt and the growing costs of its public health care system. “It’s tough sledding in this province right now.”

Islanders don’t like the border changes either, Smart says, but they’ve had little choice but to learn to live with them.

“At the root, Lubec and Campobello have existed and cooperated for a very long time, and those community roots are hard to wipe out,” he says. “Although there’s been more involvement from the federal governments in our area, people understand that either they adapt or you don’t live here.”

“If you’re still here,” he says with a smile, “you’ve adapted.”

Staff Writer Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at: cwoodard@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.