LOS ANGELES — On the afternoon of April 29, 1992, after a harrowing three-month trial of four police officers in the Rodney King beating case, jurors sent word that they had reached verdicts.

I was apprehensive as I entered the courtroom with other reporters. The verdict was being televised and we knew the announcement would surely be the biggest story of the day. But we could not know how big.

When the clerk’s voice rang out with the verdicts — four counts not guilty and one deadlock — there was a collective gasp of astonishment in the courtroom.

I remember shouts of dismay from the audience and then the reporter seated next to me said in a matter-of-fact voice: “I guess we’ll have to go cover the riots now.”

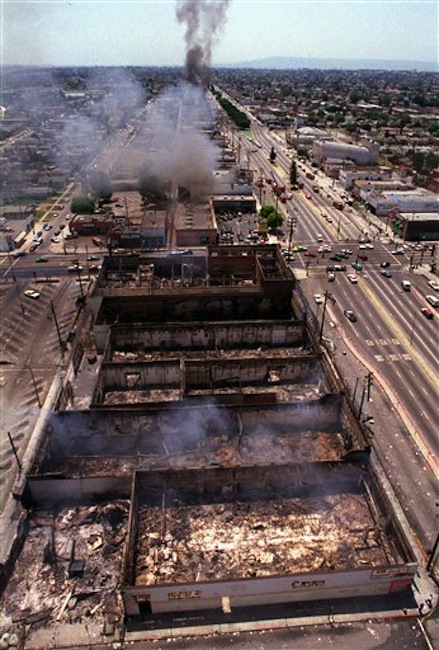

Little did she know that within minutes, violence would be breaking out at Florence and Normandie Avenues about 40 miles away in Los Angeles. Before long, the city would be a war zone.

By the time I had finished filing my verdict story, roads to Los Angeles were closed. I had been staying in Simi Valley for the trial and that’s where I remained, gathering reaction and trying to find out if I would still have a home when I returned. A neighbor told me of standing on her terrace watching the city burn. But it did not reach our area.

Marooned in Simi Valley, I went out in search of jurors and found one who said she had prayed, wept and fasted during deliberations hoping to sway other panel members to reach at least one guilty verdict. That story was a sensation and cast the verdicts in a new light. But it was too late to make a difference.

Although he was not the defendant, the trial that lit the spark for the worst riots in Los Angeles history would always be known as the Rodney King trial. We reporters thought of it that way even though King never appeared at that trial and may have never even visited the town of Simi Valley where it was held.

He was an ever present figure on videotape, a beating victim whose repeated assault by police officers with batons, boots and a stun gun was shown so many times that it seemed like a recurring nightmare. Defense attorneys dissected it, frame by frame, trying to show that King had incited his own beating.

The case had been moved on a change of venue because of saturation publicity in Los Angeles. But Simi Valley was an odd choice, a police officers’ bedroom community with a predominantly white population. There were no blacks on the jury. The brand new courthouse had no other cases under way, and it seemed as if the trial was being held in a cocoon away from the urban pressures that spawned the case.

In 1993, the U.S. Justice Department held another trial in Los Angeles in which the same officers were charged with civil rights violations. King testified in that trial, a handsome, hesitant but well-spoken and well-dressed man who described his beating and said he was taunted with racial epithets.

Verdict day was tense because of what had gone before. Mounted police surrounded the federal courthouse on a Saturday when the civic center was quiet. This time there were convictions and two officers went to prison. There was no violence.

By the time King’s federal civil suit against the City of Los Angeles was tried in 1994, everyone seemed tired. I was one of the few reporters to cover all three trials and the courtroom no longer drew standing room only crowds. The jury ultimately awarded King $3.8 million in compensatory damages, far lower than his lawyer had expected, and they gave him no punitive damages.

Three years after King was beaten, the court cases finally were over. But the city would be dealing with the aftermath for decades.

Send questions/comments to the editors.