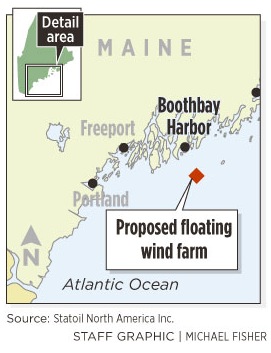

The Norwegian company that wants to build a demonstration floating wind farm off the coast near Boothbay Harbor will hold three public meetings this month to update its progress and answer questions.

Representatives from Statoil will be in Boothbay on June 25, in Rockland on June 26 and in Portland on June 27.

Statoil has been testing a floating offshore wind turbine in Norway since 2009, and says it’s encouraged by the performance of the project, called Hywind.

International energy companies such as Statoil are in a race to design wind turbines that float in deep water, rather than being anchored to the seabed. Offshore sites have stronger, more consistent wind. The challenge is to design cost-effective equipment that can withstand extreme weather and sea conditions.

Last year, Statoil filed with the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management for a commercial lease to test a four-turbine project off Maine, starting in 2016. The public meetings are meant to explain how the company is progressing with environmental studies and other tasks it will need for permits, if it decides to move ahead.

If Statoil does go forward, the Hywind Maine prototype will become the first floating, deep-water wind farm in the United States and could pave the way for a large-scale project. It also would advance Maine’s ambition to be a leader in offshore wind-energy research, and position businesses to provide goods and services for what could become a growing industry.

“The purpose (of the meetings) is to be open about our plans,” said Ola Morten Aanestad, vice president of communications for Statoil North America. “It’s in a very early phase yet. There’s no decision to go ahead, from our side.”

Statoil says it will make a decision in 2014. That’s a while away, but the fact that Statoil is taking the time to hold public meetings indicates that the company is serious about Maine, Aanestad said.

Several challenges must be overcome before turbines are spinning at the test site, 12 miles off Boothbay Harbor.

Consultants working for Statoil first must finish in-the-water studies by year’s end, on issues such as the rotating blades’ impact on migrating birds and bats. It ultimately will need a timely commercial lease and various state and federal permits.

Some of the issues the company faces were previewed in the winter, when a task force formed by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management held a public meeting in South Portland. The issues include the impact on fishing grounds and gear, shipping lanes and recreational boating. People concerned about those and other matters are expected to attend the upcoming meetings.

The test site is less than four square miles. It’s in federal waters that are more than 400 feet deep on the Outer Continental Shelf. Good wind speeds have been measured in the area, which is well beyond the view of most coastal residents.

Hywind Maine would have the capacity to generate 12 megawatts, which would meet the power needs of roughly 18,000 homes. But it’s too early to say how the project would be connected by undersea cable, where the power would be sold, and how much it would cost. The terms of a power purchase agreement for demonstration projects have yet to be announced by the Maine Public Utilities Commission.

Habib Dagher, the University of Maine professor who has led the state’s offshore wind-power effort, noted that a study last year showed the cost of electricity from a pilot project could be three times current rates, up to 30 cents per kilowatt hour. By law, the impact on ratepayers would be minimal because of the tiny output of the project.

“When we scale up to a real commercial project in the 500-megawatt range by 2020, the cost is expected to drop to 10 cents per kilowatt hour,” Dagher said.

Aanestad acknowledged that driving down the cost of power is critical to Statoil. Better-than-expected performance at the 2.3-megawatt floating turbine in Norway has given Statoil reason to look at other sites, including Maine.

But power costs won’t be competitive unless full-scale projects can be economically built and sited, Aanestad said.

Statoil also is watching to see whether Congress extends tax credits that are valuable to the wind industry.

The company’s continuing involvement is encouraging to Paul Williamson, who heads a group of businesses called the Maine Wind Industry Initiative.

“We’re all very supportive and eager to see this go forward,” he said. “It would be a transformational opportunity for our state. There are billions of dollars in investment possible.”

The Hywind design is known as a spar, basically a floating vertical tube with ballast at the bottom. That technology, and other ideas, are being evaluated by University of Maine researchers.

Dagher and his team in the school’s Advanced Structures and Composites Center had planned to deploy a one-third scale model of a different design this summer off Monhegan Island. The launch now has been reset until next year because of a delay in receiving permits.

Staff Writer Tux Turkel can be contacted at 791-6462 or at:

tturkel@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.