When Margaret Burgess arrived for her job interview at the Portland Museum of Art in 2009, she felt transfixed by a Claude Monet painting hanging in a second-floor gallery.

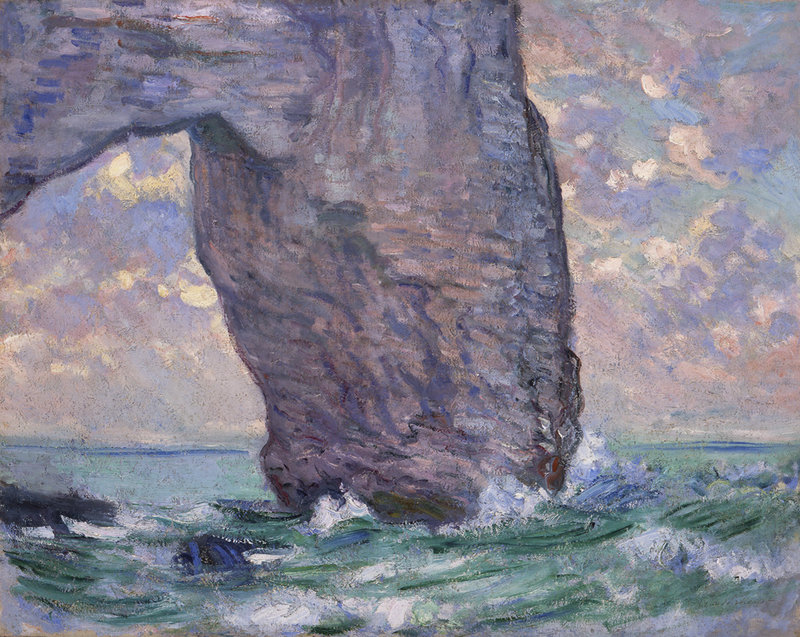

The painting, “La Manneporte Seen from Below,” painted in 1884, shows the widely depicted natural arch that is sculpted in the limestone cliffs of the Normandy coast of France. If you’ve been to the museum and wandered beyond the first floor, you know the painting. The PMA keeps it on view all the time, and it’s one of Monet’s most compelling oils.

The master’s view is from sea level, looking up and over at a small seaside section of the arch. Green waves break against the rocks, and the arch itself nearly blends into a cloud-filled sky. Monet renders the earthen form with soft greyish-blues. The painting feels rugged and suggests a dangerous place.

“I was just struck by how he chose to crop it and how this painting fit into his overall oeuvre,” said Burgess, the museum’s curator of European Art. “How he got to that vantage point and why he chose to paint from there captivated me.”

Those questions lingered for Burgess, and next week, the museum opens its major summer exhibition with the Monet painting as its centerpiece. “The Draw of the Normandy Coast: 1860 to 1960” opens Thursday and remains on view through Sept. 3.

Burgess, who got the job she coveted, has put together 43 paintings by European and American artists who have traveled to the Normandy coast for subject matter and inspiration.

The exhibition includes several visions of the arches at Etretat, including two others by Monet. Before he moved onto waterlilies and haystacks, Monet studied, devoured and dissected these arches.

“The Draw of the Normandy Coast” is a lush, warm and colorful show, with beach scenes, boats at port and tall, majestic cliffs. Set against gallery walls painted in blueberry blue, this collection of paintings conjures summer dreams. In addition to Etretat, it includes paintings from Trouville, Deauville, Villerville and the ports of Le Havre and Honfleur.

The exhibition encourages one to think about the similarities between the Atlantic coast of France and the coast of Maine. Both regions attracted the most talented artists of the 19th and 20th centuries. Both were readily accessible by rail — from Paris or Boston. Both were, and still are, endowed with stunning natural beauty, and both are dotted with cities and towns that supported the artists with summer colonies and year-round residences.

And both share the same ocean.

While the Monet painting inspired Burgess’s earliest ideas for this show, another PMA exhibition, “The Call of the Coast” in 2009, helped focus her thoughts. That exhibition examined the work created by artists in New England art colonies. This show does much the same, from a European perspective. “I loved that show, and it made me want to do the French coast,” she said.

The Normandy coast attracted artists of all ilk and style. It wasn’t just the impressionists who came here, but also the realists, neo-impressionists, cubists and surrealists. The region’s artist-visitors included some of the most important in the annals of art history, from Monet to Matisse, Renoir to Picasso.

This exhibition documents the draw of the region from the mid-19th century on up through World War II and beyond, Burgess noted. Many of the works come from the museum collection, as well as from the Scott M. Black Collection, which is on long-term loan to the museum.

Burgess and museum director Mark Bessire also solicited loans from other Maine institutions, including the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, as well as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Modern Art in New York; the Detroit Institute of Arts; the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn.; and the Smith College Museum of Art in Northampton, Mass.

In a short statement that he wrote for the accompanying catalog, Black recounted his trips to Normandy. He visited first in 1982, and returned with his wife, Isabelle, in 2008 and 2009, following in the footsteps of the artists whose works he admired and collected.

“The cliffs at Etretat with its arch were remarkable; Port-en-Bessin where Seurat painted was a delightful small village,” Black writes. “We dined around sundown at La Ferme Saint-Simeon in Honfleur, a historic inn which had hosted Boudin, Monet, and Bazille, observing from its promontory above the famous lighthouse the dappled sunlight on the bay of Le Havre that Monet had captured in his earlier works.

“Like Maine, Normandy has a rugged beauty which is well worth visiting.”

During a gallery tour, Burgess calls attention to the Gustave Corbet oil, “Stormy Weather at Etretat.” Although he was born in the mountains of France, Courbet found himself drawn to the coast. He made this painting, depicting billowing waves crashing against the rocks and cliffs, in 1869. He told his friends he was struck by “the growling sea.”

Burgess loves this painting for its emotive qualities. He painted the cliffs with a sharp palette knife, and turned the sky into a caldron of brown and gray. The waves churn ferociously.

The curator calls it a “moody coastal scene.”

It is the coast of Normandy, but could just as easily be an image of Blackhead at Monhegan in Maine, made by the hand of Rockwell Kent or Edward Hopper.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.