ROCKPORT – If art is a dialogue, then the conversation this spring at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art feels like a well-told play.

The Rockport gallery opened last weekend with a 60th anniversary “Honors Exhibition” that focuses on five artists who, through their work and career paths, reflect the mission of CMCA to advance contemporary art in Maine.

CMCA director Suzette McAvoy opened the gallery two weeks early because she felt so strongly about this season-opening show. She wanted to allow as much exposure as possible.

“These five artists continue to experiment and find new ways of working within their chosen medium,” she said while leading a casual gallery tour last week. “Through their work, they represent innovation and continue to challenge themselves. This work advances what we think about art and art in Maine.”

The five artists are among the best-known working in the state today: Sculptor John Bisbee; painters Mark Wethli, Katherine Bradford and Frederick Lynch; and photographer Todd Watts. The show is on view through July 8.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this exhibition is the common bond among these five artists. All work in Maine and draw influence from the state’s natural environment, but their work is not about Maine. They do not paint the landscape or use natural elements in their sculptures.

Yet, while Maine is not necessarily apparent in the outcome of their studio practices, none of these artists would do the work they do if not for their presence in Maine.

“Maine factors into their work, but is not reflected in it,” McAvoy said.

That says a lot about the state of contemporary art in Maine. The genre is not bound by a sense of place. Instead, Maine has become a place where contemporary art can flourish. The work being made here today would fit in contemporary art galleries or museums anywhere, McAvoy said.

CMCA can claim a lot of credit for the evolution of contemporary art in the state. It was founded in 1952 as Maine Coast Artists by a small group of artists, and moved into its current location in the old Rockport firehouse in 1967.

As part of this season-opening exhibition and anniversary celebration, McAvoy invited Maine Media Workshops graduate Jonathan Laurence to go through boxes of old photos and assemble an exhibition that tells the center’s story. He collaborated with Julie O’Rourke to present a witty and informative overview of the arts center through photos and graphics on the center’s lower level.

But the centerpiece of the season-opening show are the individual exhibitions on the main floor and loft galleries.

NEW DIRECTION FOR BISBEE

The paintings of Bradford and Wethli as well as Bisbee’s sculptures inhabit the main floor.

The first thing one notices on entering CMCA is Bisbee’s latest piece, “This Is Only a Test.” Bisbee has distinguished himself for his work with nails — bright common spikes, to be precise. He bends, twists, welds and otherwise contorts spikes into gracefully flowing sculptures. Some stand freely; others hang on the walls.

Bisbee has shown across Maine and across the country. His work is always evolving, and this piece marks a new direction. For the first time in a major way, Bisbee assembles his sculpture with bolts instead of welds.

“Test,” which looks something like an oversized wine rack, feels laden with tension. It is axiomatic; as you walk around it, its presence changes. It gives the appearance of being in motion, and extends itself into space.

McAvoy paired the paintings of Bradford and Wethli together because each artist shares a common evolution, although in different directions.

“Many years ago, when I worked at the Farnsworth (Art Museum in Rockland), I did a show with Kathy and Mark,” McAvoy said. “Back then, Mark was painting realistically and Kathy was doing abstraction. Now, 20 years later, they have switched.”

For this show, Bradford is showing recent paintings that hover between dreams and reality. These are poignant, almost musical paintings of people in the water, swimming and bobbing.

But look closely, and you will see that she barely paints the human figure at all. Her marks merely suggest a figure. They lack detail, but are full of form. She generates a lot information with minimal brush strokes and a small selection of colors.

Wethli, on the other hand, fills his surfaces with a lot of color, sharp angles and rigid shapes. For this series of work, he paints with acrylic on wood. His surfaces are found tabletops left over from the old studios at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, where Wethli teaches — as does Bisbee.

Perhaps coincidentally, or not, Bradford lives in Brunswick in the summer. So all three artists showing on the main floor also are connected geographically.

Lately, Wethli has received a lot of attention for his public art projects. He painted the mural in the Great Hall at the Portland Museum of Art, and completed two high-profile projects at the University of Southern Maine in Portland, including a sculptural piece. He has never settled into one expressive format for long before he tries something else.

These paintings are similar to the geometric color mural at the PMA in that they feature lots of colors and distinct shapes formed mostly by sharp angles. But unlike the PMA piece, his shapes here are not uniform, and Wethli has chosen not to improve his surfaces. The wood is riddled with holes and imperfections, and the paintings are somewhat loose.

As such, this body of work has a sense of history and age with utilitarian qualities.

A DISTINCTIVE PAIRING

Lynch and Watts share the loft gallery, and what an interesting combination they make.

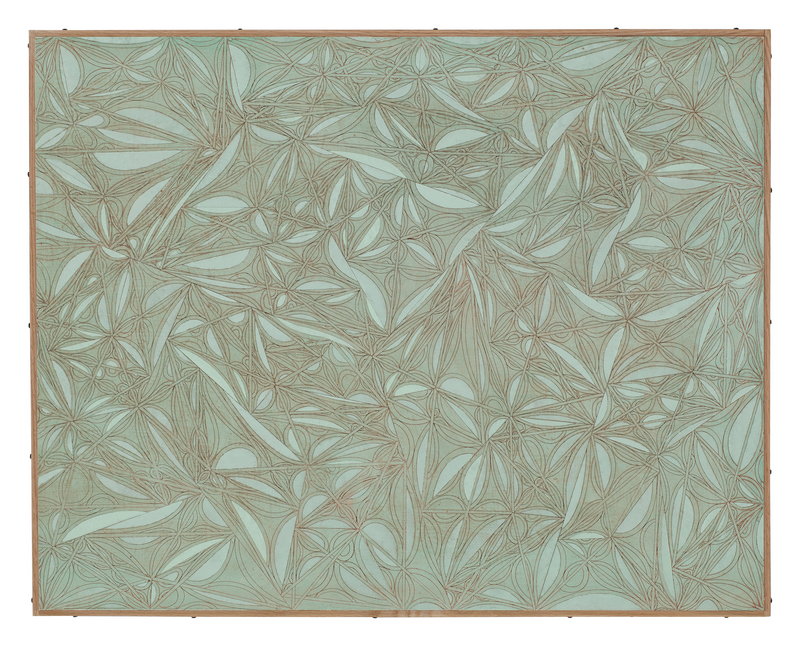

Lynch has been making art in Maine for four decades, producing a wide-ranging body of work that includes paintings, drawings, prints and his latest idiom, incised wooden reliefs. These are free-standing and wall-hanging pieces that extend from a controlled physical space.

In many of these works, Lynch extends the surface beyond what we might perceive to be the frame. Some he encases under glass, others are built up to resemble a self-contained suitcase.

Lynch has been making what he calls division paintings for years — abstract images made from a precise set of lines that result in ever-diminishing spaces. His approach reveals many shapes and forms that are discovered through a process of mark-making and sequential thinking.

For this series, he makes his incisions with a dental tool into a hard wood surface, then fills the void by applying paint. The end result looks like a fine etching. It is remarkably detailed work, made all the more complex by his decision to extend the edges of surfaces.

“He is pushing the idea of what it means to make a painting today,” McAvoy said.

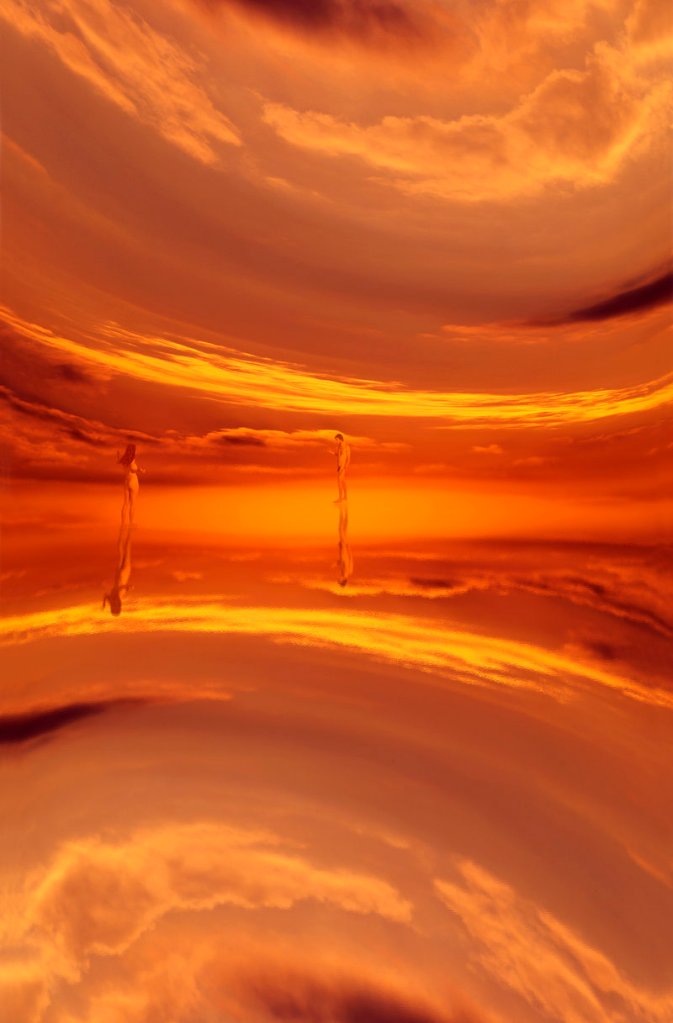

Watts occupies the back area of the loft with several large-scale photographs that look nothing like photographs. He has been making images for 30-plus years, and began his association with Maine in the mid-1970s when he bought a house next to the famous Maine photographer Berenice Abbott. He moved his New York studio to Maine in 2000.

Watts’ images begin traditionally, with a large-format camera. He then scans his negatives and manipulates them in wildly imaginative ways. His presentation involves large-scale prints, often with a single color or shades of the same color.

Oftentimes, the original photo that Watts began with it barely recognizable. As with Lynch, his frames are very much part of the final image. In that respect, the two artists share a sense of craft.

“Todd thinks of himself as an image maker more than a photographer,” McAvoy said. “He thinks of himself as a painter and his images as drawings. He is making an object, not a photograph.”

None of the artists in this show make what we might expect.

Bisbee’s nails look nothing like nails. Bradford’s realistic scenes of people at the beach feel surreal and dream-like. Wethli’s painted panels conjure ideas of ancient folk art or something post-modern. Lynch’s shapes and scratchings could just as easily be ancient scrimshaw. And Watts creates images that begin as photos but end up as something else completely.

“This, to me, is what Maine art is today,” said McAvoy. “It’s about artists expanding their boundaries and our expectations of what art is and what it’s supposed to be.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.