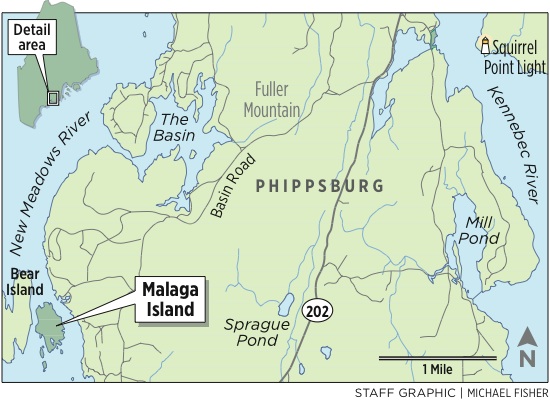

AUGUSTA — A century ago this spring, Maine Gov. Frederick Plaisted oversaw the destruction of a year-around fishing hamlet on Malaga Island, a 42-acre island in the New Meadows River, just off the Phippsburg shore. The island’s 40 residents — white, black and mixed race — were ordered to leave the island, and to take their homes with them, else they would be burned. A fifth of the population was incarcerated on questionable grounds at the Maine School for the Feebleminded in New Gloucester, where most spent the rest of their lives. The island schoolhouse was dismantled and relocated to Louds Island in Muscongus Bay.

Leaving no stone unturned, state officials dug up the 17 bodies in the island cemetery, distributed them into five caskets and buried them at the School of the Feebleminded — now Pineland Farms — where they remain today.

Several islanders spent the rest of their lives in this state-run mental institution. One couple, Robert and Laura Darling Tripp, floated from place to place in a makeshift houseboat, but, unwelcomed, wound up moored to another scrap of an island. Malnourished, Laura fell sick during a gale; when her husband returned with help, he found the couple’s two children clinging to her lifeless body. Many others suffered from the stigma of being associated with the island.

“After the island was cleared, people did not really want to talk about this incident, especially the descendants, because to raise your hand and say you were from Malaga supposedly meant you were feebleminded or had black blood in you or both,” said Rob Rosenthal, whose 2009 radio documentary “Malaga: A Story Better Left Untold” helped draw attention to what is one of the most disgraceful official acts in our state’s history. “Nobody wanted to declare that.”

Now the Malaga story is being told, openly and thoughtfully, in the shadow of the State House dome, from under which the evictions were hatched. “Malaga Island, Fragmented Lives” opened Saturday at the Maine State Museum, with descendants and Gov. Paul LePage in attendance. The exhibit tells the story not just of the eviction, but of the community it destroyed. Malaga, the artifacts, documents and photographs on display make clear, was a fairly ordinary coastal settlement at the time of the eviction.

In the late 19th century, the islands of the midcoast were dotted with the homes of hermits, squatters and fishermen. Malaga’s people lived like so many others, eking out an existence trapping lobsters, hooking cod, digging clams or laboring at boardinghouses and farms on the mainland. But the fact that many islanders were of at least partial African descent put the community afoul of the burgeoning eugenics movement, whose practitioners married racist assumptions with a social Darwinist policy agenda. And the island they occupied — and may well have had title to — was thought ripe for development as a summer colony.

“Racism is an undeniable linchpin to this story, but it is far from the only reason things happened the way it did,” said Allen Breed, a North Carolina-based reporter for The Associated Press, who has been researching a book on Malaga for more than a decade, and said there were other mixed-race hamlets on Great Yarmouth and Hen islands that were left alone. “They were on a very visible, potentially valuable piece of real estate near the mouth of arguably the state’s tourism crown jewel, Casco Bay.”

Malaga’s people were certainly poor. The island’s soil is inappropriate for farming, and fishing, laboring or doing laundry and carpentry for mainlanders didn’t pay well. Their homes were modest, and one family lived in a converted ship’s cabin. Some relied on charity from the town to get through the winter, and in 1908 private donors stepped in to help build an island school. School ledgers have survived.

“The papers written by the students show their penmanship was perfect and their spelling was better than mine,” said Lynda Wyman, a trustee at the Phippsburg Historical Society, which also will have a small Malaga exhibit this summer. “It absolutely shows that kids were educated, not illiterate or so-called feebleminded or any of those things.”

Archaeological digs by University of Southern Maine researchers Nathan Hamilton and Robert Sanford show the islanders caught lobsters, shellfish, cod and even swordfish. Thousands of buttons near the home of the island’s laundress attest to how much washing she took in from Phippsburg’s boardinghouses.

They built their homes on piles of discarded clam, mussel and scallop shells because they could be made level and provided excellent drainage. In doing so, they inadvertently gave a valuable gift to 21st-century archeologists.

“The shell middens protected almost all the artifacts and household stuff they mixed into it, and we actually know who lived on each spot,” Hamilton said. “To actually have a patch of ground where we know the name and age of the individuals associated with it, their race, their jobs and when they lived there — that’s really interesting and unique.”

The fish and shellfish remains have proven a boon to fisheries ecologists and geneticists seeking to reconstruct what area fisheries looked like in the late 19th and early 20th century. “I got into this research because I thought it would enhance the university’s African-American collection,” Hamilton said. “But when we got into this, I realized it was fantastic bioarchaeology.”

But the shell middens offered no protection from Gov. Plaisted, who visited the obscure island with his entire executive council in July 1911. That December, the governor ordered the eviction of the community, and officials institutionalized eight residents, some for failing to identify a telephone (which none had likely seen) or for not knowing that William Howard Taft had succeeded Teddy Roosevelt as president. Those who remained were given payments for their homes and ordered to leave — with or without them — by the first of July, 1912.

Later that year, the cemetery was cleared and the island sold to a close friend and business partner of the chair of Plaisted’s executive council, Dr. Gustavus C. Kilgore of Belfast, who played a central role in the creation of the governor’s policies, including signing the commitment orders for those sent to New Gloucester.

Nobody has lived on the island since.

“It’s heartbreaking to think about family members having gone through something like that that could have been avoided,” said Charmagne Tripp of Hartford, Conn., a singer/songwriter whose grandfather Harold was one of the children on that houseboat when her great-grandmother Laura died a century ago. “When you think about the greed and how you can make people so insignificant for their own gains, that’s a painful discovery.”

Over the past decade, more and more people have been discovering the Malaga story. There were articles in Island Journal, Down East, and this newspaper. Gary D. Schmidt’s children’s book on the tragedy — “Lizzie Bright and the Buckminster Boy” — won a Newbery Honor in 2005 and a lyric play based on it premiered in Minneapolis this March. Descendants spoke out in Rosenthal’s documentary, which aired on WMPG and later on Maine and New Hampshire’s public radio networks. Many descendants networked via Facebook and met in person. Others were discovering the story for the first time.

“My aunt would take me to visit my uncle in Maine, and it was one of the friendliest places I’ve ever been; everyone was so nice,” said Akinlawon Tripp, Charmagne’s brother, who also lives in the Hartford area. “You go through a series of emotions when you learn about all this that happened, that this fate came from a state that’s known as ‘Vacationland.’ I mean, the North was supposed to be the free land — what the heck went on here?

“The way everyone from the island was played — I think of my granddad, the one who was on the boat with his mom, and he would go through all these tribulations in his life. It kind of made him the way he was. But what was most disturbing to me was the fact that they moved the graves. That took the cake for me.”

But in 2010, the state finally expressed contrition. A joint resolution drafted by then Rep. Herb Adams, D-Portland, was passed unanimously at the State House and expressed “profound regret” for the numerated injustices of the incident. On a rainy day late that summer, then-Gov. John Baldacci joined a historic gathering of descendants on Malaga and delivered an apology to them for what his predecessor had done. “I thought it was very important that I go there as governor and try as much as possible to right a wrong that had been done many years ago,” Baldacci said. “I don’t think it was reflective of Maine’s history, heritage and roots.

“I have to tell you, it was very emotional. I didn’t foresee the impact of that just saying sorry would have for people.”

“I remember that day when we were out on Malaga and the governor gave his apology, and everything was silent,” said Marilyn Darling Voter of Windham, whose great-great-grandfather’s sisters, nieces and nephews were among those evicted. “When he ended it, the aspen trees started quivering (in the wind) and the sun came out. And believe me, we all noticed it. It felt like something had broken in the other realm, like literally a cracking of the lies.”

In the two years since, Rosenthal has perceived a change in the atmosphere around the story. “You could tell that a cloud had lifted, maybe not all the clouds, but most of them,” he said. “Since then, I get the sense that people in the town of Phippsburg — descendants and otherwise — perhaps feel a little freer.”

Last fall, Voter organized a family reunion of descendants of Malaga founder Benjamin Darling at the Phippsburg Congregational Church, which plays a role in “Lizzie Bright.” More than 125 people reportedly attended, including the Tripps and family friends of some of those interred at Pineland. “People can embrace it now and say, yeah, my family came from Malaga, and I’m proud of it,” she said. “We all stood and said, ‘We’re Darlings and we’re proud.’ “

The Maine State Museum exhibit — running through May 26, 2013 — will likely increase awareness of the Malaga story, which has often been told inaccurately, when it was mentioned at all. (Many accounts relied on early 20th-century newspaper stories by reporters accustomed to inventing or embellishing details.)

“We’re trying to present the facts as we know them, and bust some of the myths,” said curator Kate McBrien, who developed the exhibit.

Relatives of the Malaga evictees say having a high-profile exhibit at the state’s official museum is cathartic, but there is another step Voter would still like to see. “Closure for me is to return the bodies to the island because my aunts died there believing their bones would become part of it,” she said. “Removing the bodies was the difference between eviction and annihilation.”

Colin Woodard is State and National Affairs Writer for The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram.

CORRECTION: This story was update Sunday, May 20 to reflect that William Howard Taft succeeded President Theodore Roosevelt.

Send questions/comments to the editors.