Bob Marley packed a lot of living into his 36 years: Hit records, international concert success, 11 kids by seven different women, a face stenciled on more T-shirts than Che Guevara.

It was as if he knew he didn’t have much time, so he got an early start and lived at a sprint, despite the laid-back image his music and lifestyle portrayed.

He’s been dead for three decades, but as one of the founding fathers of reggae music, he remains an icon whose fame transcended music just as he himself transcended the odd confluence of geography, religion, patois and poverty that created him.

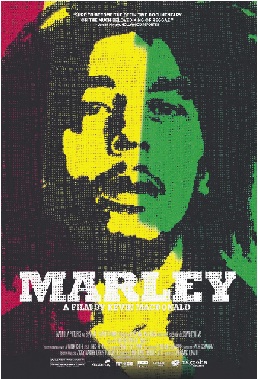

The who, where and how of Marley shine through in Kevin Macdonald’s thorough documentary about this Jamaican who introduced reggae and his religion, Rastafarianism, to the globe — a guy for whom the phrase “world music” was invented.

Macdonald, director of “The Last King of Scotland” and “State of Play,” used his clout to round up everyone — from Marley’s first teacher in rural Jamaica to his producers, colleagues, wife, lovers and children — to paint the most complete portrait of this seminal musician.

Here’s Bunny Livingston of The Wailers dancing out the chucka-chucka beat of reggae, where you play “three beats and imagine the fourth.” Jimmy Cliff relates the many musical influences on Marley and the Jamaican music scene of the 1960s, the years just after the island earned its independence. Colorful producer Lee “Scratch” Perry is shown in the studio, conducting through dance the band’s recordings. And there, in interviews and on stage, bouncing around the microphone in near religious ecstasy, is Marley, putting poetry into music that first took over Jamaica’s dance halls and then conquered the world.

Rastafari, with its ganja-smoking, dreadlocks-wearing, Haile Selassie-worshiping mysteriousness, is explained. This is some of the most fascinating footage, showing how Bob, an “out caste” thanks to the white father he never knew, found a father figure in the charismatic Mortimer Planno, a preacher of the “liberationist” Jamaican religion that reimaged Christianity through Afro-centric eyes.

The red-letter dates in Marley’s career, from his first single (“Judge Not”) in 1962 (he was 16) to the “tipping point” concert that made him an international phenomenon, to his hard-won breakthrough in America, are captured.

Friends and colleagues remember the political naivete, the assassination attempt, the mania for soccer that injured him and set in motion the disease that killed him. Hints about the sort of “career first” advice he was getting sneak in. We hear, from a daughter and son, what a feckless husband and absentee dad he was.

One omission is Marley explaining his creative process. There are many interviews, but reporters of the day were caught up in his hair, his history, his religion and his marijuana use, and they never nailed down much about where the poetry came from.

We hear how he worked out melodies and incorporated topicality into his lyrics, but not how he wrote the anthemic “One Love,” how he thought of “Stir It Up” or “I Shot the Sheriff.”

Still, “Marley” manages to be something close to a definitive history of a man whose music has endured as the genre evolved in the decades after his death. And every now and then, the film comes close to placing us where the music often did — in the realm of the mystical, with a beat everybody could dance to.

Send questions/comments to the editors.