There’s no shortage of books by, and about, Americans living in Paris. Yet the new title by acclaimed author and Colby College alum Rosecrans Baldwin adds a smart, contemporary voice to the genre. Baldwin’s year-and-a-half stay in Paris yielded a bumper crop of tales and truths that make for a winning memoir.

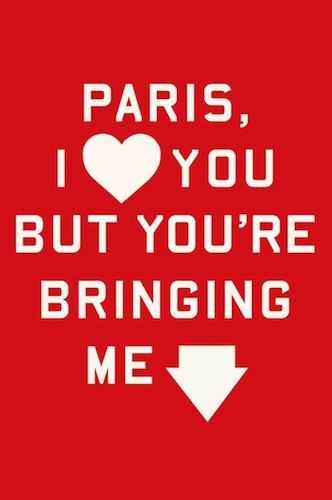

“Paris, I Love You But You’re Bringing Me Down” is a blend of portrait and caricature, where the City of Light is hardly the lone target. Baldwin casts a witty eye on all things French, not least of which is his own fixation, from the age of 10, with the nation’s capital. “For a long time,” he says, “I’d thought Paris had the world’s best everything.”

Fast forward a couple of decades, and the author, now 36, grown up and married, has lived the expatriate dream both for better and worse.

The story begins with a plum job offer from a friend, Pierre, whose Paris ad agency needs a “creatif,” a copywriter who can attend meetings in French yet write ads in English for a global clientele. In theory, Baldwin, then a budding novelist, is a plausible candidate; in fact, however, his French, at least initially, proves better suited to the accidental comedy that would become his daily life.

Gaffes and miscues seem to trail him. In one scene, where he has just spilled water on the front of a colleague’s suit pants, his apology is more egregious than the original offense. Later, in a wincingly funny exchange, he discovers that his French is so bad that it inadvertently produced racial slurs.

“Each day, I brainstormed, I presented, I butchered the French language bloody,” he says. “It was petrifying.”

Nor were his errors confined to the language. French office culture holds its own mysteries — imponderable at times — to all but natives. When and whom to greet with “bises” (kisses), for instance, would remain puzzling throughout his time in Paris. All the while, he noted that people in the act looked purposely bored and detached.

“September found me frequently biseing inappropriately,” he says. “Gradually, I learned to bise in the local mode. There weren’t any guidelines, just intuition. It required months of calibration.”

The book moves easily between the personal and the political, from the realities of Paris, 2007 — with its union workers on strike, bikes and mopeds zipping madly around town, and George Clooney hawking Omega watches from posters everywhere — to the customs of daily living.

For the author and his wife, life in Paris is a mixed bag of romance and red tape, a jumble of contradictions not unlike the city itself. Living on the Right Bank, they’re an easy walk to many of the nation’s fabled spots, and yet, their apartment is a virtual construction site with renovation noise on all sides.

At dinner parties they attend, people debate the city’s pros and cons — its iconic beauty versus the insularity, tourism and high cost of everything. Meanwhile, a culture bent on rules and protocols churns out voluminous paperwork, from which Baldwin is not exempt.

When his wife, Rachel, joins a Paris gym, filling out an application proves to be just the preamble. She has to supply two photos, copies of her passport, a recent bill and apartment lease, residency application and a notarized document proving that she has health insurance.

Baldwin serves up a potpourri of treats, among them the sort of one-liners that travel memoirs tend to spawn. He describes seduction in Paris as “the base syrup of most exchanges, business or otherwise.”

Of Parisians falling in love, he says, “They respected love like they did beauty: among life’s highest states.”

“Bureaucracy,” he notes, is “France’s first sport.”

Baldwin richly conveys the mix of dislocation, triumph and homesickness that often accompanies expatriate life. Along the way, we meet a cast of characters, two of whom — the author’s co-worker, Bruno, the quintessential Parisian, and Rachel’s American friend, Lindsey — animate their every scene. And the book’s subplot, about the novel-in-progress that Baldwin stealthily re-writes in Paris, has a jubilant finale.

As he prepares to leave France, Baldwin tries to name the syndrome whereby one is actually in Paris and missing it at the same time. Readers may finish this book with a similar fondness.

Joan Silverman of Kennebunk writes op-eds, essays and book reviews for numerous publications.

Send questions/comments to the editors.