OGUNQUIT –– When Ron Crusan became director of the Ogunquit Museum of American Art in 2009, he made one bold pledge to his board.

“I told them, ‘I want to be the most exciting art museum in Maine. That’s my goal.’ “

The museum certainly is making strides.

This week, Crusan and his staff will open the seasonal museum early for the second year in a row, hoping to give locals a reason to visit it before the tourists arrive.

The seaside museum opens on Tuesday with “Light, Motion, Sound: 2012,” an exhibition of work by 15 Maine contemporary photographers. Before Crusan arrived on the scene, the museum opened in July and targeted mostly summer residents and tourists.

Crusan’s strategy for expanding the museum and its reach is multi-faceted:

• Open early in the season and stay open late in an attempt to shift the museum’s reputation as a summer-only destination to a three-season option.

• Invigorate the exhibitions by showing more of the permanent collection, which includes almost 2,000 pieces by some of the most iconic artists who have painted in Maine, including John Marin, Rockwell Kent and Marsden Hartley, as well as a large collection of paintings by the museum’s founder, Henry Strater.

• Complement the traditional Maine art with the best contemporary art created in the state.

Last year, Crusan opened early with an installation by Portland artist Lauren Fensterstock. In 2010, he gave Harpswell sculptor John Bisbee a show.

This year, it’s a contemporary photography show curated by Denise Froehlich of the Maine Museum of Photographic Arts. The exhibition includes installation, video, mixed media, new media, sculptural and two-dimensional photographic works.

CUTTING-EDGE PHOTOGRAPHY

The roster of artists in “Light, Motion, Sound” includes Caleb Charland, Elke Morris, Barbara Goodbody, Jonathan Laurence, Raphael DiLuzio, Todd Watts, Amy Stacey Curtis, Luc Demers, Mat Thorne, Tad Beck, Noah Krell, Maggie Foskett, Mark Ketzler, Dan Dowd and John Paul Caponigro.

The work is spread over three galleries. Some images hang on the walls; others hang from the ceilings.

Laurence is showing 365 small transparencies shot with his iPhone on each day of the year. He suspends them from the ceiling with fishing twine, arranging them in such a way that visitors can walk through as if in a maze.

Goodbody made her “Indra’s Net” series of abstracted and geometric images while shooting from her porch at night. She turned them into large-scale inkjet prints, prodding the viewer to consider the heavens and universe.

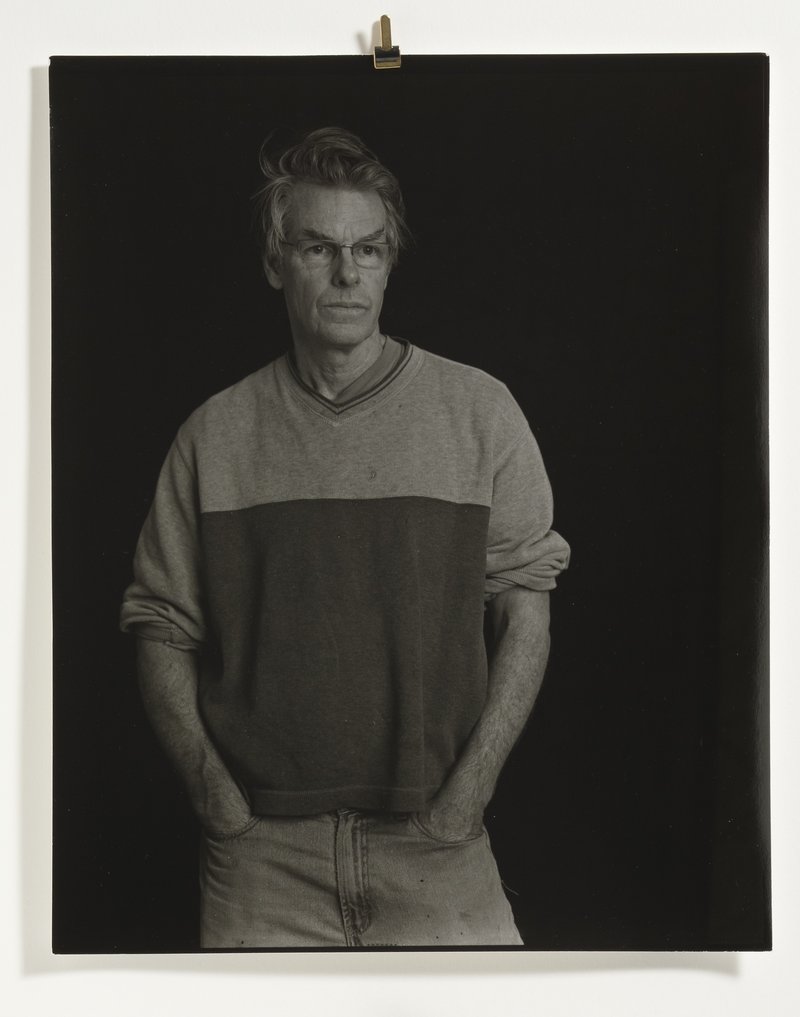

Demers is showing what he calls his “Memory Portraits.” He photographed several of his Maine art contemporaries with a traditional 8-by-10 view camera while they concentrated on a specific memory, which they later wrote down and sealed in an envelope. The images are printed and framed, and the sealed envelope is displayed underneath. The viewer is left to ponder the memory, able to surmise it only by reading the subject’s face.

Froehlich was thrilled to find a willing partner in Ogunquit. “Light, Motion, Sound” is anything but a traditional photography show, with its mix of two-dimensional and experimental photography in a variety of media. The Maine Museum of Photographic Arts wanted a collaborator willing to take risks.

“We found that in Ron,” Froehlich said. “He contacted us and said, ‘What do you want to do?’ We said, ‘Something super cutting-edge,’ and he jumped on board. Ron is the contemporary art guy in the state right now, and we’re very happy to be showing here.”

BUILDING ON A SENSE OF PLACE

It’s an interesting time for Ogunquit. Of all the museums in Maine, the Museum of American Art has been among the most traditional and safe.

Before Crusan moved here from Connecticut, the Ogunquit museum opened in July and closed up with the end of summer. It catered to seasonal residents and tourists, and focused largely on traditional Maine art.

Crusan saw opportunity, and convinced the board to let him flex.

“I talk to artists all the time who have never even been here,” he said. “We need to let them know we are here.”

The museum opened in 1953, on a site along the coast where Edward Hopper once painted dreamy images of dories. Strater, who had a successful career as a painter, founded the museum as a way to celebrate Ogunquit’s rich tradition as an art colony dating to the late 1800s.

When Strater died in 1987, he left much of his own work as well as his personal collection to the museum. He built his collection through personal relationships with the artists of his day and their widows, and also made several key purchases.

It’s a deep collection, Crusan said.

“I look at some of what we have, and I think any museum in the country would like to own this work,” he said.

One of the missions of the museum is to “tell the history of the Ogunquit art colony, which is so important to American Modernism,” Crusan said. Part of that collection includes a sculpture garden on the museum grounds. Two wooden animal pieces by the late Maine sculptor Bernard Langlais, a bear and a lion, are in dire need of repair. Crusan secured a $5,000 grant and raised $5,000 to match it to pay for repairs, which will begin this summer.

In June, Ogunquit will mount a show by New York and Maine painter Will Barnet, who is still making art at age 100. Other artists scheduled for shows this year include Peggy Bacon and Carlo Pittore, as well as a spotlight on the Mail Art Movement.

Crusan is confident the museum is on the right path.

“When I started, people didn’t know who we were unless they lived here,” he said. “So I made a point of going to Portland and going to openings all over the state and introducing myself. I think people know who we are now, and I think people are interested in what we are doing.

“Someone up north told me, ‘Everything south of Portland is part of Massachusetts.’ So I told him, ‘My goal is to give you a reason to come and visit.’ I think we are doing that.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.