AUGUSTA — Just weeks after Farmington police shot and killed Army veteran Justin Crowley-Smilek outside the town’s police station, Kennebec County Sheriff Randall Liberty set in motion a plan to teach law enforcement and corrections officers how to deal with people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

The first fruits of that labor were seen Wednesday when more than three dozen first responders from agencies across the region took part in training aimed at recognizing PTSD and how to approach those who are suffering from it.

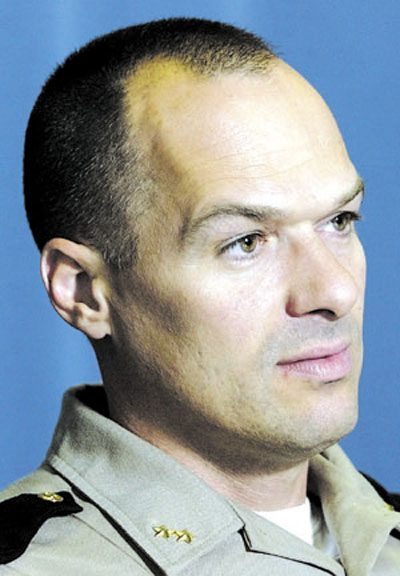

“We thought it was critical to form a dialogue,” said Liberty, an Army veteran of the war in Iraq. “If the first responders have a more informed approach, maybe we can prevent something like that from happening again.”

The half-day training held at City Center was created with support of VA Maine Healthcare Systems at Togus, said Capt. Marsha Alexander, administrator of the Kennebec County jail. Planning began in December, roughly a month after Crowley-Smilek, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan, was shot multiple times while reportedly wielding a knife and threatening Farmington Police Officer Ryan Rosie.

But Crowley-Smilek’s shooting and the July 2010 shooting of veteran James Popkowski by Togus police and Maine Game Wardens on Togus grounds only highlight what is an ongoing issue for first responders, such as police, medics and firefighters.

Liberty said an uptick in domestic violence and regular encounters with veterans trying to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol have had a significant impact on law enforcement. The Maine Chiefs of Police Association and Maine Sheriffs Association have had ongoing discussions on how to meet those challenges, he said.

“As first responders, obviously, we’re dealing with these folks,” Liberty said.

The class attracted law enforcement and corrections officers from as far away as Washington County and from agencies such as Bread of Life Ministries. Togus psychologists David Meyer and Chantal Mihm offered an overview of PTSD and other veterans’ issues and treatment options.

An estimated 20 percent of the 2.1 million American soldiers who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001 are suffering from PTSD or some other mental health problem, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. More soldiers die from suicide than combat, it says.

PTSD is caused by traumatic experiences, such as the violence of battle. The more exposure to such events, the greater the risk of sometime later developing PTSD symptoms, including persistent frightening thoughts and memories, sleep problems, feeling detached or numb or being startled easily.

It’s not known exactly what changes in the brain to cause the symptoms or why similar experiences will trigger the illness in some people and not in others.

Capt. Robert Gross, jail administrator for the Washington County Sheriff’s Office, recalled a female inmate who had been raped while in the military. The jail setting triggered several episodes during which the woman lashed out, Gross said. Corrections officers believed she was suffering from PTSD, but none knew how to help her.

Gross, who had known the woman for years, said he spent considerable time trying to counsel the woman, but he lacked the proper skills.

“I think corrections have done a poor job by not knowing about this,” Gross said. “We’re learning as we go. This training is long overdue.”

Corp. Bryan Slaney, a corrections officer at the Kennebec County jail, said the class offered the tools corrections officers need to help veterans and others struggling with PTSD to move on with a normal life and not return to jail.

“We encounter people daily that have PTSD,” he said. “It gives us the tools to keep them safe and help them.”

Slaney said officers at the jail have gotten better at identifying the signs of PTSD and at times have even been able to help sufferers identify undiagnosed disorders.

“After learning about it you can put your finger on it,” Slaney said. “Whether they know or not, I’m not sure, but they didn’t say they had it.”

Callie Campbell, a clerk at the Kennebec County jail, said it is easy to forget the personal struggles of the inmates who come and go from the jail.

“It’s been a huge eye-opener,” she said. “There are external circumstances people deal with daily that affect them here.”

Craig Crosby — 621-5642

ccrosby@centralmaine.com

RESOURCES FOR HELP

* National Veteran Suicide Hotline: 1-800-273-8255 (Press 1 for veterans)

* VA National Call Center for Homeless Veterans: 1-877-424-3838

* National Institute of Mental Health: www.nimh.nih.gov

Send questions/comments to the editors.