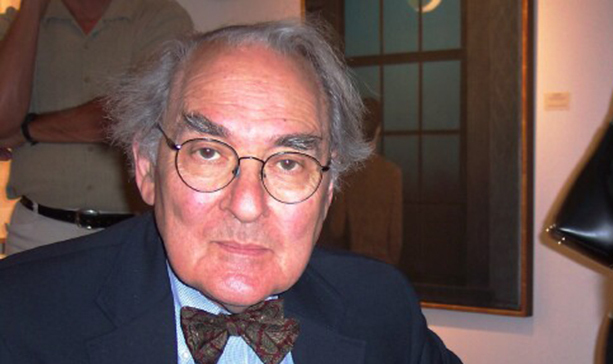

Hilton Kramer’s place in Maine was defined by much more than the Harpswell dateline that appeared in newspapers around the world announcing the news of his death last week.

Kramer, 84, died Tuesday at a nursing home in Harpswell, the result of heart failure. He lived in Damariscotta.

His career as an art critic very much centered on New York. He was chief art critic for The New York Times for many years, and then turned his attention to the New Criterion, which he edited. Kramer began his career as a critic in the 1950s, and joined the Times in the mid-’60s.

To be sure, Maine played a larger role in Kramer’s life than simply as a place for retirement or escape.

He and his sweetheart, Esta, came to Maine for the first time in 1963. She was working for a magazine in New York and became friends with a member of the Paul Taylor Dance Company, who offered her a summer place in Phippsburg. Esta came to Phippsburg with her two cats, and Kramer joined her a short time later that summer for a brief vacation.

Their romance bloomed. They were married the next year, and had been coming to Maine ever since.

It’s not out of the realm of reason to surmise that maybe their summer romance in Phippsburg led to their marriage. And anyone who knew the Kramers surely can attest how deeply in love Esta and Hilton were.

He might have been known as an eminent art critic, but first and foremost he was Esta’s husband, and their life in Maine represented the depth of their love.

Esta is an avid gardener. Like many people who live in New York, the Kramers felt the need to get away, and they got away to Maine.

They stayed in many places along the coast, and in 1987 they bought a house in Waldoboro. In 2002, they moved to Damariscotta.

Kramer knew Maine for its role in the art world long before he became a full-time resident. He was familiar and passionate about the work of Lois Dodd and Alex Katz through their time in New York, and he championed the work of Cranberry Island artist Emily Nelligan. He also counted himself a fan of Louise Nevelson.

Significantly, the Kramers’ art collection, comprised of works from friends in the contemporary art world, will be coming to the Portland Museum of Art by bequest.

Susan Danly, senior curator at the PMA, got to know Kramer through his art collection.

“He had a very sharp mind and a wonderful eye. He had a sense of quality and connoisseurship in an old-fashioned way,” Danly said. “He didn’t tolerate much about commercial hype. He trusted his own instincts about an object, and that is what he brought to his criticism. He was quite open-minded, and would look at a range of things.”

During his years at the Times, Kramer developed a reputation for his “imperious judgments,” the newspaper wrote in his obituary, published Wednesday. “He was a passionate defender of high art against the claims of popular culture and saw himself not simply as a critic offering informed opinion on this or that artist but also as a warrior upholding the values that made civilized life worthwhile.”

Kramer’s conservative opinions did not endear him to his peers of other artists, but his voice was healthy for public discussion, said Felicia Knight of Scarborough, who spent many years working for the National Endowment for the Arts. She admired his mind and his uncompromising standards.

“He was an erudite, deeply knowledgeable critic who certainly provided a more conservative voice in arts criticism,” Knight wrote in an email.

The artist Dozier Bell knew Kramer by reputation before she knew the man personally. She heard about his conservative politics and his rumored lack of respect for artists whose work was the talk of the town. Her opinion changed when she learned more about him.

“When I finally began reading his collected criticism, I was very sorry I hadn’t started reading it earlier, back when I was a young artist seeing some of the same shows he had reviewed,” she said in the days after his death.

“His impressive erudition came across with remarkable clarity, style, and often humor, making his summaries of the art historical precedents and contemporary art world context for a given show a welcome educational opportunity. That alone might have been enough to make me keep reading him. But it was his insistence on art as a worthy and serious spiritual endeavor, a way of connecting to who and what we are, that sold me on his criteria and got me enthusiastic about being an artist again.”

That’s high praise, and as good a thing an artist could say about anyone — critic or peer.

Although he was known as a New Yorker, Kramer was a New Englander at his core. He was born in Gloucester, Mass., and learned the arts as a young man in Boston.

He made his career in New York. But as soon as it made sense for them to do so, he and Esta took up residence as full-time Mainers for the last, long chapter of their life together. It began nearly 50 years ago in Phippsburg, played out gloriously for many years on the midcoast and ended, sadly, on a quiet spring day in Harpswell.

So that Harpswell dateline that we saw on Wednesday was much more than a final marker of this man’s life. His time in Maine reflected well on his values and his passions, as well as his heart.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.