Second of two parts

During the first two weeks of October, a Cumberland County resident ingested something nasty — a virulent bug known as salmonella that thrives in uncooked ground beef.

The bacteria went on the attack, and sometime over the next three days this person started experiencing painful and distressing symptoms that likely included violent diarrhea, abdominal cramps and fever.

A doctor did an examination and sent a stool sample to a local laboratory. On Oct. 22, that sample tested positive for salmonella. The laboratory worker who did the test, required by law to report cases of salmonella, immediately notified the Maine Health and Environmental Testing Laboratory in Augusta.

Over the next few weeks, three more Mainers were stopped in their tracks by a similar sudden illness. And more incidents were being reported in Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, Kentucky and Hawaii.

So began two months of medical sleuthing during which public health investigators in seven states quizzed people who got sick about their eating habits and other personal routines, trying to piece together the puzzle.

Ultimately, this detective work, along with technology that helped link together the 20 known cases, led investigators to the source of the illness — ground beef sold at Hannaford supermarkets.

This type of public health investigation is a long process that unfolds in its own time, controlled by the nature of the disease, the timing of laboratory tests and old-fashioned legwork.

“Some people think there’s a case of salmonella today and we know about it tomorrow, and it doesn’t work that way,” said Dr. Stephen Sears, Maine’s state epidemiologist.

There are 40,000 cases of salmonella reported in the United States every year, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, making it the most common cause of foodborne illness. Add in cases that go undiagnosed or unreported, and the actual number of infections may be as much as 1.2 million.

The total number of foodborne illnesses is even higher. The CDC estimates that 1 in 6 Americans, or 48 million people, are sickened by a foodborne pathogen each year.

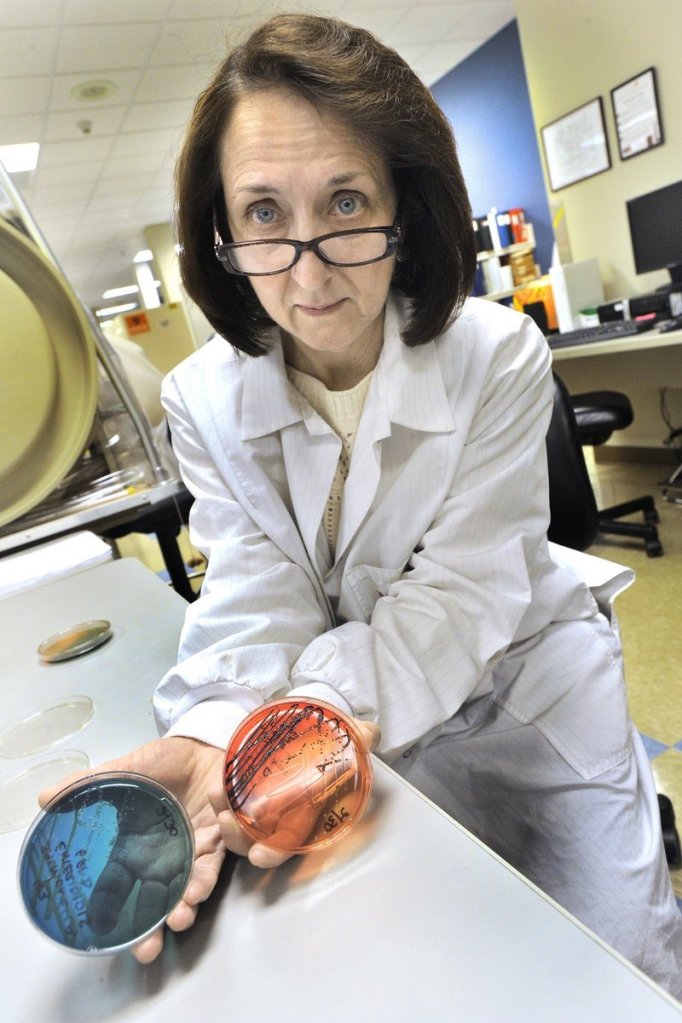

In the state’s public health lab, the microbe ingested by that first Cumberland County patient was identified as Salmonella Typhimurium — a rarer strain of salmonella that is resistant to antibiotics, and therefore may be more likely to lead to hospitalization.

“All salmonellas are related to each other, but just like people have some genetic distinguishing factors, there are some genetically distinguishing aspects to salmonella,” Sears explained. “And that’s found through what’s called PFGE, which stands for pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. That’s a genetic examination of the organism, and so you’re looking at the genetic pattern.”

The microbe’s genetic fingerprint went into a national database called PulseNet so that it could be compared to salmonella samples uploaded by scientists in other parts of the country. This molecular surveillance system helps investigators link cases of foodborne illness even though they may have happened hundreds of miles apart. It greatly speeds up the process of determining whether a case is an isolated incident, or part of a larger outbreak.

As more people became ill in the Hannaford outbreak, a lab worker in Augusta uploaded the Maine salmonella samples into the system. An epidemiologist at the federal CDC in Atlanta who regularly reviews these and other samples sent in from all over the country, searched for matches that would signal an outbreak.

A week after the Cumberland County resident’s case was reported to the state, another case came in from Androscoggin County. Two weeks later, there was a third case reported from Waldo County. Then a fourth one came in from York County at the end of November.

Meanwhile, on the ground, a much more low-tech investigation was going on.

“At the time when we first were investigating the individual cases, we did not know they were connected, especially because they were in four different counties and none of the people were related to each other,” said Vicki Rea, a Maine CDC field epidemiologist based out of Bangor.

As soon as a new case of salmonella, or any other reportable disease, is reported to the state, an epidemiologist calls the physician who originally ordered the test to make sure the health care provider has informed the patient about the diagnosis.

“We like for the provider to tell the patient first, before we sort of call out of the blue,” Rea said.

The epidemiologist gets the patients’ contact information, and someone from the physician’s office alerts the patient to expect a call from the state.

“When we call, we just introduce ourselves and basically try to say this is a routine investigation, we’re trying to determine where you might have been exposed to this,” Rea said.

In all, four local field epidemiologists were on the ground, working these cases.

The epidemiologist asks the patient questions using a five-page questionnaire that covers everything from demographic information and symptoms to exposures to foods, places and circumstances that might have made them sick.

Do you handle food for a living? Have you had contact with a diapered child or adult, or had contact with someone else who appears to have the same illness?

Have you been traveling? Did you eat at any restaurants during the exposure period, and where? What did you eat? Was it undercooked? Have you shopped at grocery stores, farmers markets or roadside stands during the exposure period? Have you had any contact with animals? What’s the source of your drinking water?

A lot of people might find it difficult to remember what they had for dinner last night, much less 10 days ago. If the patient can’t remember, the investigator may ask if a particular food is something they would generally eat in their diet.

“Some people say for sure they don’t eat meat, or they don’t eat fish, or that kind of thing,” Rea said. “That helps a little bit.”

Most of the time the interview is done over the phone, but epidemiologists will go to visit patients in the hospital if they are very ill.

In Maine, two of the salmonella victims were sick enough to be hospitalized.

“Generally speaking, people are hospitalized because they are dehydrated,” Sears said. “They often have underlying illness that’s made much worse (by the salmonella infection), so if they have heart disease, lung disease, diabetes, cancer, something like that, they’re the ones that are most vulnerable to these conditions.”

Usually when a salmonella case pops up in Maine, it’s an isolated case that can’t be linked to any other cases, Sears said. But when PulseNet starts making connections through genetic fingerprints, health officials know they have a potential outbreak on their hands.

“In this case, we found over time four organisms of salmonella that were the same PFGE pattern,” Sears said. “They were in different geographic locations, and then those began to match some that were seen in several other states in New England. When that happens, you ask the question ‘Is there a common vehicle for this?’ Or is there some common contaminant somewhere along the way?”

By early December, the federal CDC epidemiologist looking for genetic fingerprint matches had connected the dots on PulseNet and identified a potential multi-state outbreak of salmonellosis. At this point in an investigation, the CDC dispatches its “OutbreakNet” team to lead the effort to track the disease, and to coordinate communication between public health officials in different states.

The state also assigns its own outbreak team to work on the investigation, Sears said, but “once this becomes a national issue, it really is taken over by the national folks, and we have a lot of conference calls.”

Rea became the lead epidemiologist in the investigation, conferencing with the CDC and reporting to Sears and the deputy state epidemiologist.

Officials from the Food Safety and Inspection Service, the public health arm of the USDA, began visiting Hannaford stores, examining its logs for grinder use and talking to store employees.

Michael Norton, director of corporate communications at Hannaford, said the visits provided “some insight that something’s going on, but not an epidemiologist saying ‘Here’s what we think we’ve got.’ “

“They’re not saying we’ve got an outbreak of illnesses associated with ground beef at Hannaford,” Norton said.

Then, on Dec. 15, Hannaford officials joined federal and state public health officials on the conference call that declared an outbreak and launched a recall of Hannaford ground beef.

Once investigators know they have an outbreak on their hands, field epidemiologists from the Maine CDC begin contacting patients once again to inform them that they are part of a cluster of illnesses, and that they need to complete a second, more targeted questionnaire — in this case, one that asks more specific questions about their exposure to ground beef.

Throughout the process of tracing the illnesses to their source, it was never a given that the salmonella originated in ground beef, even after that became the scientists’ number one hypothesis. There have been salmonella outbreaks around the country connected to peanut butter, alfalfa sprouts, vegetarian snacks, chili sauce, cantaloupes, fresh produce, white pepper, salami and other foods.

It can take months to figure out the source and test it. But sometimes, investigators get lucky. In this case, they found that two of the sick patients, one in Maine and one in New York, still had ground beef at home. They were told not to throw it out, and not to eat it, though they probably didn’t need any convincing on that point.

The meat went to a lab for testing, following a paper chain of custody.

Even when the source of contamination is believed to be in hand, sometimes they can’t be sure. If a package of ground beef has been opened, there’s always the potential for cross-contamination.

“The food that someone has left may not have been the source, but it may have been contaminated from the source,” Sears said. “What it makes you do is be very careful about saying something is truly associated until you have strong statistical evidence, and that’s often very challenging to come by.”

The salmonella outbreak eventually sickened 20 people in seven states, according to the official tally. There could be more people who fell ill, but didn’t feel sick enough to go to a doctor.

Maine health officials have kept watch for new cases, and also took a look in the rearview mirror.

“We went back and looked at all our salmonellas,” Sears said. “Did we miss anything?”

On Feb. 1, the CDC issued a statement saying that the outbreak appeared to be over.

Sears said the relatively small number of cases documented during the investigation may suggest that a small number of organisms got into a limited amount of product.

“If you really had a significant amount of organisms, you probably would have seen more cases,” he said.

Staff Writer Meredith Goad can be contacted at 791-6332 or at:

mgoad@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.