MIAMI — Wearing a hoodie. Listening to music and talking on his cellphone. Picking up Skittles for his soon-to-be stepbrother. Friends say that’s how they would have imagined 17-year-old Trayvon Martin on a Sunday afternoon.

Starting a fight? Possibly high on drugs and up to no good? No, friends say that description of Martin from the neighborhood crime-watch volunteer who shot and killed the unarmed black teenager doesn’t match the young man they knew.

“There’s no way I can believe that, because he’s not a confrontational kid,” said Jerome Horton, who was one of Martin’s former football coaches and knew him since he was about 5. “It just wouldn’t happen. That’s just not that kid.”

Martin was slain in the town of Sanford on Feb. 26 in a shooting that has set off a nationwide furor over race and justice. Neighborhood crime-watch captain George Zimmerman, whose father is white and mother is Hispanic, claimed self-defense and has not been arrested, though state and federal authorities are still investigating.

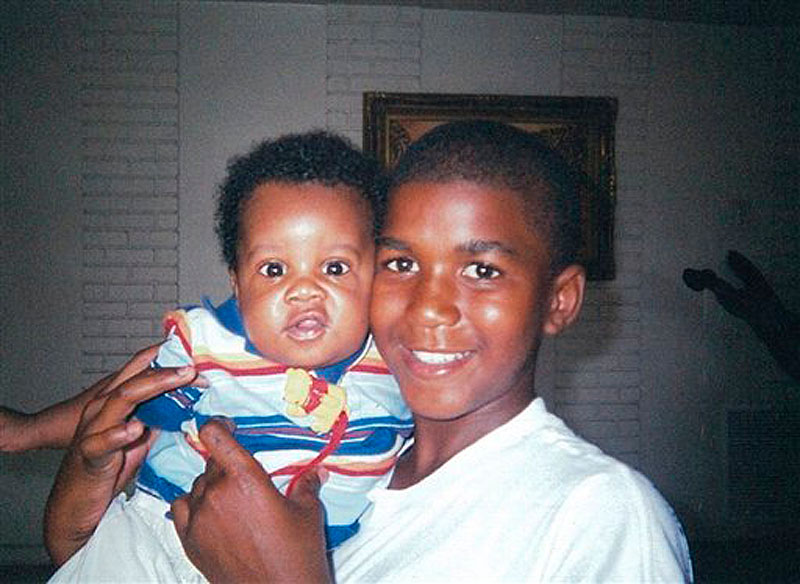

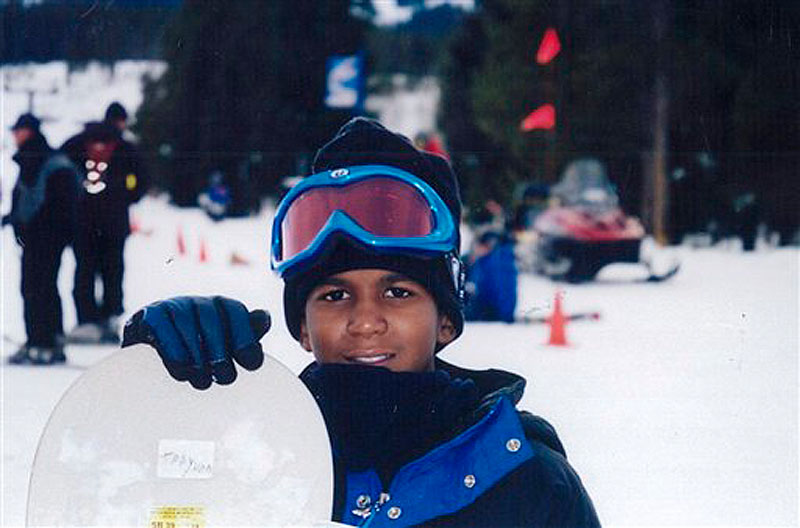

Since his death, Martin’s name and photographs — in football jerseys, smiling alongside a baby, and staring into the camera in a gray hoodie — have been held up by civil rights leaders and at rallies stretching from Miami to New York demanding Zimmerman’s arrest.

On Friday, President Barack Obama called the shooting a tragedy, vowed to get to the bottom of the case, and added: “When I think about this boy, I think about my own kids.”

Since the slaying, a portrait has emerged of Martin as a laid-back young man who loved sports, was extremely close to his father, liked to crack jokes with friends and, according to a lawyer for his family, had never been in trouble with the law.

The son of divorced parents, he grew up in working-class neighborhoods north of Miami’s downtown. He and his father, a truck driver, were active in the Miramar Optimist Club, an organization that runs sports and academic programs for young people. Tracy Martin, the teen’s father, coached his son’s football team.

The boy was a swift athlete, according to a friend, and played a range of positions up to about age 14. After he stopped playing, he remained active in the organization, volunteering six days a week from June through November of last year to help run the team’s concession stand.

Martin cooked hamburgers, hot dogs and chicken wings alongside his father at the stand. He loved talking to the kids, asking them what position they played and whether they were good, Horton recalled. He would call the mothers “Ma’am,” and if they had a stroller or an item they needed help with, Martin stepped in.

“Everyone out there loved him,” Horton said.

Martin was tall and lanky — only 140 pounds, according to the family’s attorney — and his nickname was “Slimm.”

The teen spent a big part of his week living with his father in a one-story, peach-colored home. Neighbor Fred Collins Jr. said he would see Trayvon Martin outside every week mowing the lawn and trimming the trees. The teen also helped Collins’ son learn how to ride a bike.

“He was coaching him, giving him words of advice, encouragement,” Collins said.

No one answered the door on a recent afternoon, and a child’s plastic tricycle sat in the driveway.

Tracy Martin often recounted how his son saved his life. The elder Martin had begun heating up some oil to fry fish and fell asleep. The grease caught fire, and when Tracy Martin awoke and tried to put out the flames, he spilled the oil on his legs, severely burning himself. Trayvon Martin pulled his father out of the home and called 911.

Martin’s parents kept a close eye on him, but they didn’t have to be too strict, since he stayed out of trouble, Collins said. However, he had recently been suspended from school for five days for tardiness, his English teacher, Michelle Kypriss, told the Orlando Sentinel. School officials did not respond to a request for comment.

Martin’s father was not happy and grounded the teen for the duration of the suspension.

Trayvon “knew he was wrong,” Horton said.

Because of state privacy laws regarding juveniles, Sanford police spokesman Sgt. David Morgenstern said he could neither confirm nor deny the family’s claim that Martin had never gotten in legal trouble.

Martin dreamed of becoming a pilot. He had flown on school vacations to various places around the country with his mother, skiing in Colorado one year, going off to Texas another.

“There’s no little black kids that want to be pilots,” Horton joked with him when he was about 13.

“Well, I’ll be the first one,” the teen replied.

At Dr. Michael M. Krop High School, where Martin was a junior, he was on the quiet side, but he would sit in the middle of the classroom, participate in class and especially liked math.

Schoolmates remembered his humorous side.

“Brrrrian!” he would call out, rolling his r’s as is done in Spanish, whenever 16-year-old Brian Paz got a phone call from his Colombian mother, the friend recalled.

“I’d just burst out laughing,” Paz said.

Paz and other friends said Martin liked rap music and funny movies. He had written some lyrics, though he hadn’t had a chance yet to perform them. Martin was especially a fan of a student musical group at his school called Bison. He had two of the group’s pins on his backpack and helped spread the word about shows.

John Emmanuel, 17, said the group was about encouraging young men to be strong, independent leaders.

“That’s how we liked to think of ourselves,” Emmanuel said.

Martin had gone up to Sanford to visit his father’s fiancée, who lived there with her young son. Friends said Martin regarded the boy as his little brother and had been looking forward to watching the NBA All-Star game with him that weekend.

On that Sunday, Martin went out to get candy and an iced tea at a convenience store and was walking back to the fiancee’s townhouse. Zimmerman, 28, spotted him and told a police dispatcher: “This guy looks like he is up to no good — he is on drugs or something.”

After the shooting, Zimmerman claimed that Martin attacked him as he was returning to his truck.

But Martin’s friends said they find that hard to believe. They said they had never seen him fight at all.

“As far as attacking the guy without him attacking him, no way,” Horton said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.