“Edgar Degas: The Private Impressionist” features a large number of canceled prints, many student drawings (he studied under Ingres), and a large and interesting group of works by his contemporaries.

While the show is supposed to be the Robert Flynn Johnson collection punctuated with a few choice pieces from the PMA, the additions generally eclipse the Johnson collection. This is not to disparage Johnson’s collected works, because Degas (1834-1917) at his worst is still brilliant.

While the catalog is a beautiful object fit for a sophisticated collector like Degas (who owned 1800 works by Daumier, for example), the essays are basically a trough of self-congratulatory drivel. And the unnecessarily defensive tone about the relative weakness of the collection also feels a bit nepotistic.

“The Private Impressionist” offers an unusual view of Degas. It is tempered by the taste of a single collector and features many minor and rarely published works which, together, make for a worthy perspective on the great artist.

Degas looms like a giant. But always, it seems, at a distance. He was daunting to his contemporaries, and he is daunting to current scholars and critics. The critic I most admire, Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker, wrote this past year that he has “never understood” Degas.

Why is Degas so elusive when he is so well known and popular? For starters, people have tried to read too much into his personal narrative. In brief, he was born into a wealthy aristocratic family, changed his name, was a founding member of the Impressionist group, was a dedicated bachelor who spent a great deal of time in brothels not having sex, and developed a reputation as a misanthropic hermit who lived the last few years of his life largely in solitude. He was a grumpy genius with a notoriously cruel wit.

Maybe it’s just that Degas’ own situation allowed him to see life as an urbane collection of visible conventions enforced by the status quo. I think he saw culture and public life as theater — well choreographed and fully scripted. If Degas were gay, in other words, that wouldn’t explain his work, but rather how he came to see modern life as a pageant of arbitrary and expected conventions.

The two most important purveyors of modernism were Degas and his old friend, Edouard Manet. Manet’s masterpiece “Luncheon on the Grass,” for example, featured two men (portraits), a naked woman (a nude) and their still-life picnic, all set in a landscape with a woman bathing behind them (pastoral). While it’s weird to us, it would have been even weirder to the audience of 150 years ago, because they would have immediately recognized what Manet was playing at.

Degas is far more subtle. He exposed the visual conventions of everyday life in cultural terms that transgressed boundaries such as theater, public space, private life or even the boudoir. Many prints in “The Private Impressionist” focus on the theatrical conventions of brothels as prostitutes, making their intentions (and goods) clear to potential patrons.

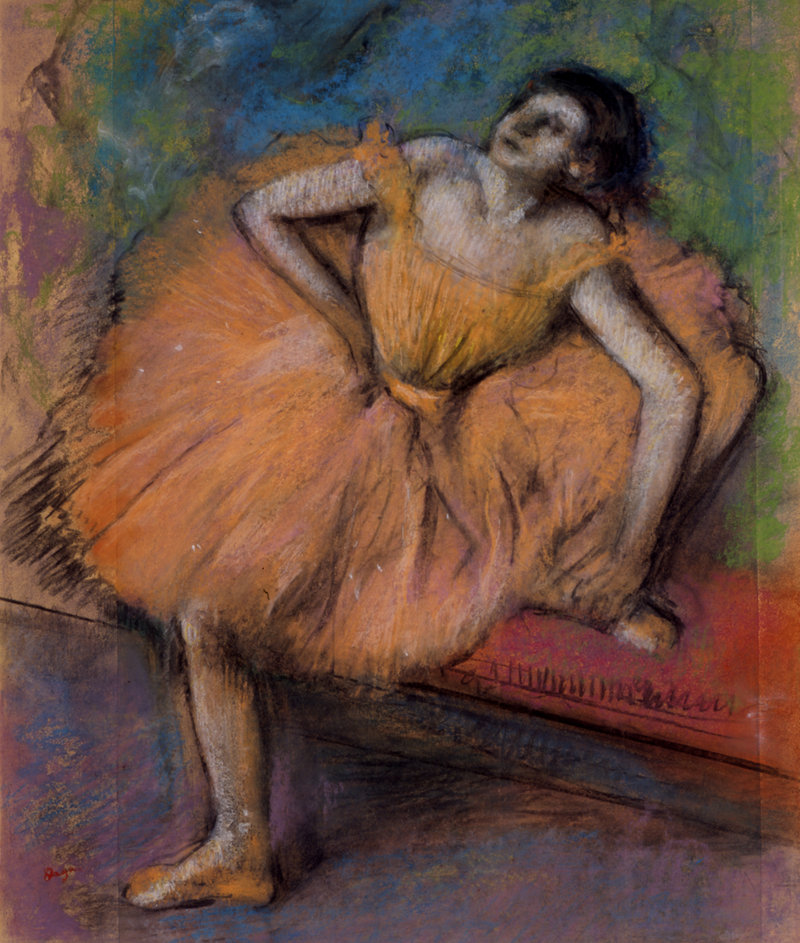

Degas shows us scenes of well-scripted public entertainment: Jockeys, singers, dancers and artists who are no longer people but something closer to rhetorical figures.

His ballet dancers, for example, are in legible poses — such as his bronze “Fourth position in front on the left leg.” While it is one of the most exciting pieces in the show, we should remember only one of Degas’ sculptures was cast in his lifetime. He made hundreds of such clay figures to capture poses so that he could see them from any angle — like a three-dimensional dictionary.

How Degas used such imagery is illustrated in works like the great pastel “Dancing Lesson.” A ballerina dances in the center space while another stretches behind her, and the choreographer stands to her left with the very light of the room emanating from him. Degas echoes himself in the choreographer — two masters fluent in the language of the body.

It was a great curatorial move to place the print “The Singer” next to the “Dancing Lesson.” In both, a strong vertical runs from the top of the image down to the central figure’s left-oriented face. Degas uses this device to control the viewer’s eye as well to start a process that both follows and reveals a visual narrative of gesture, legibility and punctuation (highly sophisticated formalism). We not only learn about the performers but what’s expected of us — the viewers — as well.

The stage lights hit the singer from below. It’s a well-rehearsed scene, and we know how to play our role. It’s her moment in the limelight maybe, but she’s there for us.

Berthe Morisot reported that Degas once said “the study of nature was worthless, since painting is an art of conventions.” While this might sound like a rejection of realism, Degas is hinting that social and cultural realities require study, since without them, forms have no meaning. This prefigures cubism, pop art and many other important strands of contemporary art — including abstraction.

Arguably, Degas did as much as anyone to lead the way to contemporary painting. He’s that important.

If you go to “The Private Impressionist” expecting scads of large oils and famous paintings, you might be disappointed. If you go to learn more about Degas, you are in for a treat.

Freelance writer Daniel Kany is an art historian who lives in Cumberland. He can be contacted at:

dankany@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.