Before Martin Luther King Jr. was able to draw national attention to the cause of civil rights in this country, there were other African Americans who laid the groundwork for the movement.

Beginning in the early 20th century, African-American activists were trying to change laws and minds. While today many of us know about the movement in the 1950s and ’60s, including marches and bus boycotts, fewer of us know about the work that was going on in civil rights during the 1920s, ’30s or ’40s.

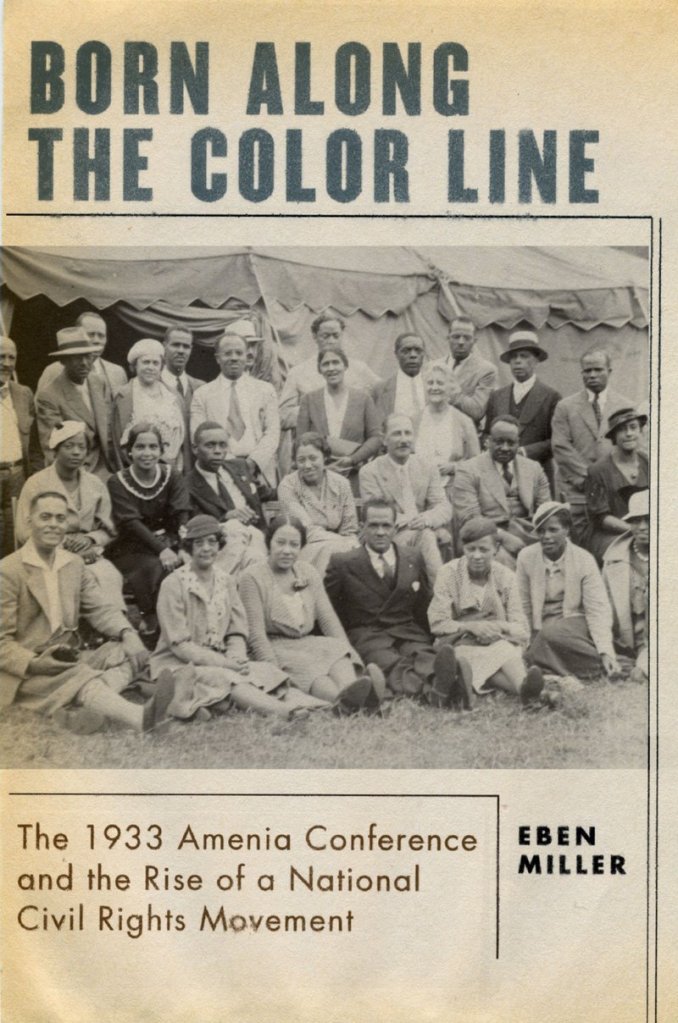

The work of that earlier generation of activists is at the core of a new book by Eben Miller, “Born Along the Color Line: The 1933 Amenia Conference and the Rise of a National Civil Rights Movement” ($29.95, Oxford). The book looks at how the attendees of the Amenia conference helped shape the ongoing fight for civil rights.

Miller, 37, is a professor of history at Southern Maine Community College in South Portland. He grew up in Maine, graduated from Bates College, and lives in Lewiston. This is his first book.

Q: How did you get the idea for this book?

A: I was really interested in writing about this remarkable generation of African-American civil rights advocates struggling to secure civil rights between the 1920s and 1950s, the generation before Martin Luther King. I saw a photo of this conference (at Amenia, N.Y., in 1933) and thought about who they were and what backgrounds they had. I realized this was a good representation of this really important civil rights generation. Then it was the legwork of finding out who everybody was, what surviving materials there were.

For me, this is the generation that lays the groundwork for so much. They were responsible for a lot of the legal litigation that creates a structure later advocates would build on. They also were concerned about a lesser-known theme at the time that King would pick up on later, that of economic equality.

Q: What was the impetus for this conference?

A: The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) was in real dire straits in the early 1930s. It was during the Great Depression, and funding was drying up. Local branches were fizzling out, and the early guard of founders were aging, passing away. There was a sense that the NAACP’s traditional outlook of using litigation and legislation wasn’t capturing young people’s attention.

So the idea of the conference was to ask young African Americans what they thought was important, what they saw as the future of the civil rights movement. Joel Springarn (the head of the NAACP’s board of directors) volunteered his home, and he and other leaders picked some young people to attend, about 30. Springarn (who was Jewish and white) was independently wealthy, and he was one of the many NAACP officers of the time who thought of themselves as sort of new abolitionists, building on the abolitionist traditions.

Q: Did some of the 30 become famous or notable?

A: One of the most recognizable names was Ralph Bunche, who became a United Nations diplomat and won a Nobel Peace Prize for his work in the Middle East in the 1940s. I tended to write about the less well-known people. There was one, Louis Redding, who became a lawyer in Wilmington, Del., when there were still no African-American lawyers there. Lawyers had to apprentice, and no white lawyer would take on an African-American apprentice. So he started this incredible community effort to change that practice and became a lawyer.

Q: What are some of the direct effects of the conference?

A: In the wake of this conference, the leaders of the NAACP felt it imperative to create a national network of activism. The hope of some who were at the conference was to make the civil rights movement more about economic equality than it had been in the past.

One of the conference attendees, Juanita Jackson from Baltimore, Md., was hired by the NAACP to help build a network of youth councils. She was just 20, but she did an amazing job of creating these auxiliary branches for young people.

It’s interesting to see what happens in the mid-’30s, after this conference, that there’s a wave of legal efforts, such as trying to pass anti-lynching legislation.

Staff Writer Ray Routhier can be contacted at 791-6454 or at:

rrouthier@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.