HANOVER, N.H. — You know Dasher and Dancer and the rest of the gang. But do you recall, the most “Perfect Christmas Crowd-Bringer” of all?

That’s how executives at Montgomery Ward originally described Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, who first appeared in a 1939 book written by one of the company’s advertising copywriters and given free to children as a way to drive traffic to the stores.

Curious to know more about how Rudolph really went down in history? It’s all in the pages of a long-overlooked scrapbook compiled by the story’s author, Robert L. May, and housed at his alma mater, Dartmouth College.

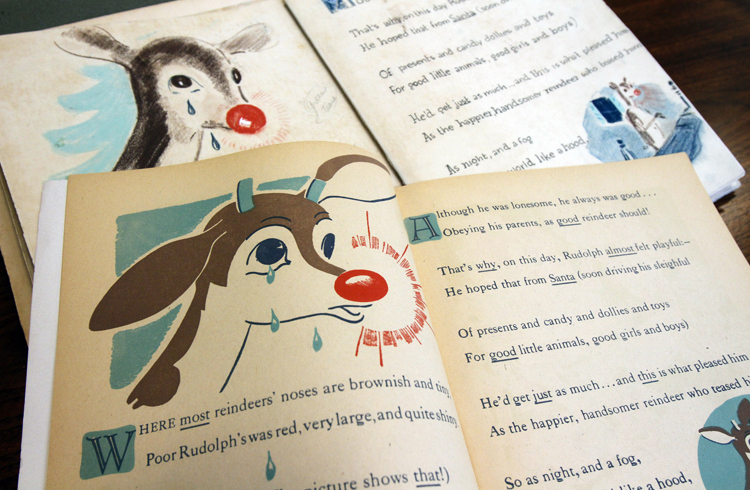

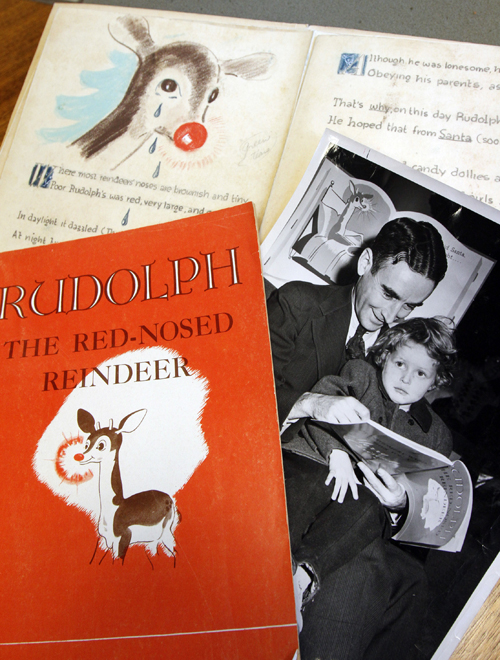

May donated his handwritten first draft and illustrated mock-up to Dartmouth before his death at age 71 in 1976, and his family later added to what has become a large collection of Rudolph-related documents and merchandise, including a life-sized papier-mache reindeer that now stands among the stacks at the Rauner Special Collections Library. But May’s scrapbook about the book’s launch and success went unnoticed until last year, when Dartmouth archivist Peter Carini came across it while looking for something else.

“No one on staff currently knew we had it. I pulled it out and all the pieces started falling out. It was just a mess,” Carini said.

The scrapbook, which has since been restored and catalogued, includes May’s list of possible names for his story’s title character — from Rodney and Rollo to Reginald and Romeo. There’s a map showing how many books went to each state and letters of praise from adults and children alike.

The scrapbook also chronicles the massive marketing campaign Montgomery Ward launched to drum up newspaper coverage of the book giveaway and its efforts to promote it within the company.

Near the front of the scrapbook is a large colored poster instructing Montgomery Ward stores about how to order and distribute the book. An illustration of Rudolph sweeps across the page, his name written in ornate script. There are exclamation points galore. “The rollinckingest, rip-roaringest, riot-provokingest, Christmas give-away your town has ever seen!” ”A laugh and a thrill for every boy and girl in your town (and for their parents, too!)”

Rudolph is described as “the perfect Christmas crowd-bringer,” if stores follow a few rules, including giving the book only to children accompanied by adults. “This will limit ‘street urchin’ traffic to a minimum, and will bring in the PARENTS … the people you want to sell!”

The response was overwhelming — at a time when a print-run of 50,000 books was considered a best-seller, the company gave away more than 2 million copies that first year and by the following year was selling an assortment of Rudolph-themed toys and other items.

But lest this become a story about corporate greed, it should be noted that in 1947, Montgomery Ward took the unusual step of turning over the copyright to the book to May, who was struggling financially after the death of his first wife.

“He then made several million dollars using that in various ways, through the movie, the song, merchandising and things like that,” Carini said. “I think it’s a great story because it shows how corporations used to think of themselves as part of civil society and how much that has changed.”

May eventually left Montgomery Ward to essentially manage Rudolph’s career, which really took off after May’s brother-in-law Johnny Marks wrote the song (made famous by Gene Autry in 1949), and the release of a stop-motion animated television special in 1964.

Both the song and movie depart significantly from May’s original plot, however. In May’s story, Rudolph doesn’t live at the North Pole or grow up aspiring to pull Santa’s sleigh — he lives in a reindeer village and Santa discovers him while filling Rudolph’s stocking on a foggy Christmas Eve.

“And you,” Santa tells Rudolph, “May yet save the day! Your wonderful forehead may yet pave the way!'”

May’s story is written in verse, similar to “The Night Before Christmas” by Clement Clarke Moore, and opens, “‘Twas the day before Christmas and all through the hills/ The reindeer were playing … enjoying the spills.”

“It’s lovely to hear it read out loud, it really comes alive,” Virginia Herz, one of May’s daughters, said in a phone interview this week.

As a small child, Herz, who declined to reveal her age, didn’t think there was anything unusual about growing up in a house surrounded by Rudolph merchandise. It wasn’t until she was older that she realized her father’s job of “taking care of Rudolph” was a bit different. She tells her grandchildren that their great-grandpa wrote a story about Rudolph, not that he created the character.

“As I child, that’s how I felt. I knew my dad had written a wonderful book about Rudolph and now there were Rudolph toys and other things all around us,” she said. “But it was no different than the guy next door who sold cars, or the guy down the street who was a painting contractor.”

She acknowledges the myths that have become entwined in Rudolph’s history — including the notion that May wrote the story as a Christmas gift for his older daughter, Barbara, when his wife was dying of cancer and that a Montgomery Ward manager “caught wind of the little storybook.” In reality, Montgomery Ward assigned May to write a Christmas book around the same time his wife was ill, Herz said.

“”What’s out there on the Internet is a softer telling,” she said. “My dad was aware of it and considered it appropriate. There’s the softer, romantic version and the more fact-based version.”

Herz said her father would be thrilled to see how his creation and its many incarnations have become part of American culture.

“I think he would be startlingly amazed,” she said. “It really is an eternal part of Christmas. He would have been amazed.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.