BRUNSWICK – In the years immediately after World War II, photographer Todd Webb split his time between New York and Paris.

He was in middle age by then, turning 40 in the war’s final year of 1945. But these were his formative years as an artist, and two of the great cities of the world provided Webb with near-limitless fodder for his documentarian’s eye.

Webb, who died in Maine in 2000, is the subject of a new exhibition at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art in Brunswick. “After Atget: Todd Webb Photographs, New York and Paris” is on view through Jan. 29.

The exhibition includes more than 60 black-and-white photos on loan from the Portland-based Webb estate, as well as 10 Eugene Atget photographs from the George Eastman House.

The show draws attention to Webb’s work during the important postwar years, and also adds context to Atget’s influence on Webb. The latter point is hardly profound. Atget, who died in 1927, is widely considered one of the great documentarians of Paris, and his work has influenced generations of photographers.

But Webb felt a different kind of kinship with the French photographer. His friend and fellow photographer Berenice Abbott introduced him to Atget’s work.

“I had never even heard of Atget,” Webb once said. “But when Berenice told us about him it seemed to me that I was doing the same thing in New York that Atget had done in Paris a half-century earlier.”

With a few side-by-side comparisons, Bowdoin curator Diana Tuite draws out the common strengths of the photographers while highlighting some of the unique aspects of Webb’s work.

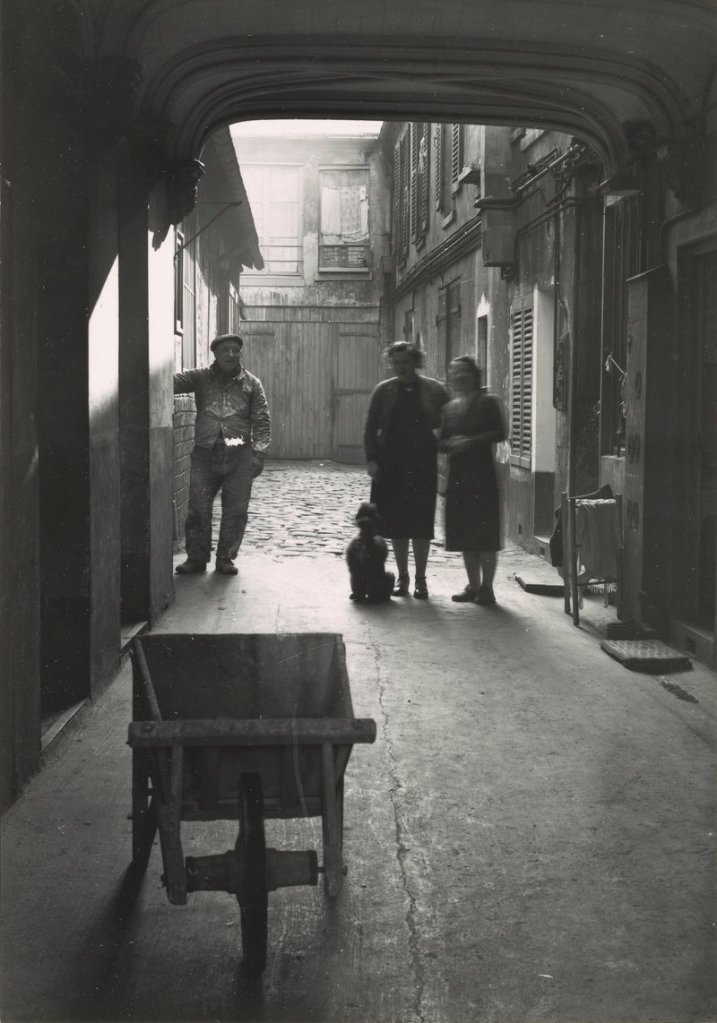

Webb used many of the same approaches as Atget, personalizing his work with humanistic respect for his subject. He added layers of social and cultural observations, filling his images with signs of the times: “Welcome Home” banners in New York; a cobbler’s shop in Paris that announced an end to war-time rationing.

More than capturing a time and place, the photographs in this show come close to capturing the mood of the people and their cities without actually capturing many of the people. Some of Webb’s work includes images of folks on the streets, but much of it suggests a human presence by capturing the aftermath of their activities, Tuite said.

“In putting the show together, I was really drawn to the searching quality in Webb’s photos,” she aid. “He attempts to describe the anatomy of a city like New York or Paris, approaching them almost naively, without preconceptions, and he does not rely on figures — but rather on their traces — to animate spaces.

“He is perceptive, but is often working indirectly, using the connective tissues of signage, cinema and public transportation, for example, to describe the social condition.”

Webb was innately curious, said Betsy Evans Hunt, executive director of the Webb estate. She got to know Webb and his wife, Lucille, when they moved to Maine in the late 1980s.

Hunt called him “self-effacing, lovely and down to earth. He grew up a Quaker in Detroit, and that informs a lot his sensibility. Simplicity was his motto. He always liked to be unencumbered. He did not have a lot of possessions and he had no need for wealth. He loved to have fun. He was an explorer and was not afraid of whatever the next step would be.”

Hunt ran a gallery in Portland at that time, and the Webbs attended every show. “It was interesting to get to know them,” she said. “He had always been on my radar screen, and I imagined he had a dealer, which he didn’t. We forged a relationship that began as a professional relationship and became more of a family relationship.”

The Webbs became elders in Hunt’s life. She inherited his estate and collection of work, and made it her mission to get his work out in front of as many people as possible. She worked closely with Tuite and the Bowdoin staff to put this show together.

“I feel it is my mission to elevate Todd into the pantheon of where he deserves to be,” Hunt said. “He’s never been quite on the radar screen in terms of visibility like Walker Evans or Berenice Abbott. My job is to get shows like this to happen and travel them, to get catalogs and publications and spread the word via exhibitions, scholarship and education.”

Next year, the Museum of the City of New York plans an exhibition, and the estate is working on several educational projects that will raise awareness of Webb and his work.

Webb lived a curious life. Although he was best known as a photographer, he did not pick up a camera until he was in his 30s. He was a stockbroker, but lost all his wealth in the Great Depression. He joined a camera club in 1938, and took lessons from Ansel Adams. He served in the Navy during World War II, and after his discharge went to work as a commercial photographer.

Webb made his first trip to Maine as a photographer for Standard Oil, photographing the construction of a pipeline from Portland to Montreal.

In 1946, he formed one of the most important friendships of his life when he met the noted art dealer and photography promoter Alfred Stieglitz.

Stieglitz helped Webb get his first New York show, in 1946, and three years later, he was off to Paris. In 1955 and ’56, he won Guggenheim fellowships to photograph the early trails of the settlers of California and Oregon. He spent three years walking across the country with his camera. While out West, he befriended Georgia O’Keeffe, and eventually spent a decade in New Mexico.

Over the arc of his career, Webb became known primarily for his work in New York, Paris and the American West.

The Bowdoin show focuses on a small but vitally important segment of that career.

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or:

bkeyes@pressherald.com

Twitter: pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.