This is not a movie review because I haven’t seen the movie.

I’m sure I will see “Moneyball” because I enjoyed the book, love baseball and will probably need to see some more of it after the playoffs and World Series are over.

But what I’m sick of is the whole world that “Moneyball” represents, in which we are told to ignore what we see with our own eyes and believe what the numbers tell us. No banker with an adding machine would have come up with mortgage-backed securities filled with toxic assets, but the smart guys with the computers did, and we are all paying the price.

It’s time we stopped being so quick to trust the smart guys.

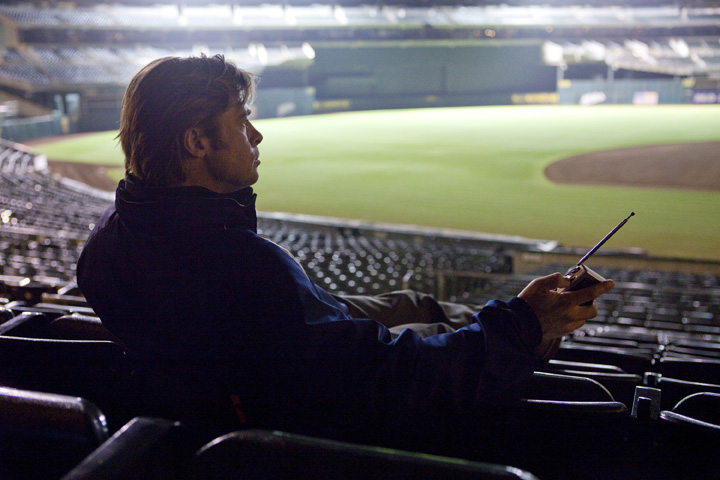

For the uninitiated: “Moneyball” is the story of smart guy Billy Beane, the general manager of the Oakland Athletics, who had some surprising success with a low-payroll ball club.

Using statistics, Beane found ways to recognize value that traditional baseball experts missed because they were blinded by a rigid culture.

Baseball scouts, Beane found, were obsessed with irrelevant details, like players who “looked like” ball players. (They even noted when a prospect had “the good face.”) They valued foot speed and paid premiums for players who could run fast. They got excited about flashy fielders.

But when Beane ran the numbers, he found that a great glove man, depending on his position, only saved a few runs more than an average player over the course of a season and wasn’t worth twice the money. And being able to run fast was almost never worth paying for in a sport where there’s not much running.

His biggest insight was that a high batting average, the gold standard for generations of bubble gum-card-memorizing American boys, was not as great as it looked.

A batter who only swings at balls in the strike zone might hit for a lower average but could get on base just as often by taking more walks. Combined with low-average hitters who hit the ball far when they connect, you could put together a cut-rate lineup that could score more runs than their higher-priced opponents.

So Beane did that, and his team of scruffy-looking, slow-footed, defensively adequate sluggers who only swung at strikes gave high-priced teams like the New York Yankees fits for a few years.

It is a made-for-Hollywood story – the ragtag team of castoffs beating the favorites by using what they have arrogantly overlooked – like David picking up a rock and slaying Goliath.

But here in reality, it’s important to remember that “Moneyball” never really worked.

For one thing, in the Bible, David killed Goliath, but the A’s never beat the Yankees.

And despite all the attention to batting statistics, the real source of Oakland’s success was the fact that the team had three young pitchers come out of its farm system, Mark Mulder, Barry Zito and Tim Hudson, who all got good at the same time. If you put those three pitchers on any team, regardless of the talent-evaluation system, it would have won a lot of games.

Oakland had no special formula for turning out great pitchers, and since the Big Three left, the team has never been able to repeat the feat. It wasn’t the computers; Billy Beane just got lucky.

In a recent interview, Beane lamented that he didn’t have a Hollywood ending for his story, but I remember the end.

It was on Oct. 13, 2001. The A’s had just beaten the Yankees twice in New York and had flown back to California, having to win only one of the next three to move on to the championship round of the playoffs.

Yankee pitcher Mike Musina was holding onto a 1-0 lead in the seventh inning when Oakland’s Terrence Long doubled to right with slow-footed Jeremy Giambi on first base.

Yankee outfielder Shane Spencer let go a miserable throw, over the heads of all his cutoff men, destined to bounce around in foul territory and give Giambi enough time to run around the bases twice.

But that’s not what happened. All the way across the diamond, Yankee shortstop Derek Jeter sensed trouble.

He sprinted across the field headed toward a point on the first base line about halfway between home plate and the bag.

On a dead run he reached out and gloved the ball with his left hand and seamlessly flipped it to the catcher with his right, never slowing down or looking at his target.

The throw beat the runner, the Yankees won 1-0, took the next two games and the “Moneyball” A’s lost their best chance to slay a giant.

A faster runner would have scored, so even though you may not need speed every day, it’s still valuable.

And more importantly, there was Jeter’s play. There is no statistic that could have predicted it because it had never happened before.

But one of Beane’s maligned scouts, one who might have watched Jeter on the field as a high school player, talked to him after the game and met his parents, might have gotten a sense that in addition to “the good face,” this kid had the instinct, drive and love of the game that could help him do something spectacular.

We like to think that there is truth in the numbers, but sometimes we need to remember to open our eyes and believe what they tell us, too.

Greg Kesich is an editorial writer. He can be contacted at 791-6481, or: gkesich@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.