PORTLAND — Earle Shettleworth was only 13 when he stood on a sidewalk on St. John Street and watched the Union Station Clock Tower crash into rubble and dust on Aug. 31, 1961.

When the dust settled, he sneaked past workmen and grabbed a piece of pink granite as a souvenir. He keeps it in his office in Augusta, where he has been director of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission since 1976.

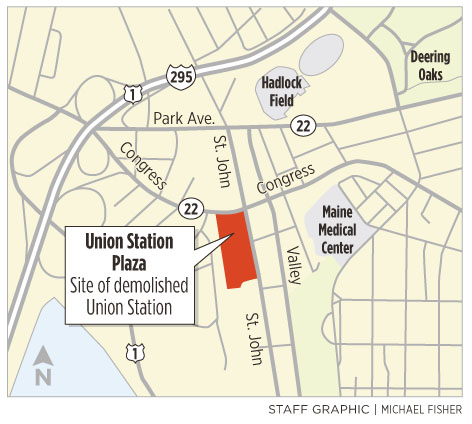

As a young history buff, Shettleworth understood that the demolition of the grand old railroad gateway was a terrible loss. Many people had personal connections to the station because it had been a transportation hub for more than 70 years. He couldn’t have known that its destruction – to make way for a strip mall – would spark a preservation movement in Portland and across Maine that continues 50 years later.

“It happened so quickly,” Shettleworth recalled Tuesday. “Passenger service ended in 1960, and before you knew it, Maine Central Railroad was selling off all its properties, and there was nothing to stop them. It made people realize that major components of the city’s history could be destroyed with the flick of a finger and they needed to take steps to protect it.”

Three years later, activists formed Greater Portland Landmarks, an organization that has worked to preserve the city’s tangible history through decades of change and modern development. Shettleworth, then a Deering High School student, was one of its first members. John Calvin Stevens II, namesake grandson of the famous Portland architect, was its first president.

“The demolition of Union Station was the pivotal event for the historic preservation movement in Portland,” said Hilary Bassett, executive director of Greater Portland Landmarks. “It focused community awareness on the importance of preserving the amazing architectural legacy that defines Portland.”

Completed in 1888, Union Station was a primary connector between the Boston & Maine Railroad and the Maine Central Railroad, linking Boston to all points north of Portland. Before the Maine Turnpike made railroad travel obsolete, the station was where kids left for summer camp, couples launched honeymoons and parents sent their sons off to war.

For some people, the station’s destruction was like losing a loved one, but they couldn’t stop progress.

“The automobile was taking over, that was valuable land and it was during the era when they liked to knock stuff down and build new,” said John Marcigliano of Westbrook, an educator and the author of “All Aboard for Union Station.”

The station was designed by Bradlee, Winslow and Witherell of Boston to resemble a medieval French chateaux, Marcigliano said. It had steep roofs, sloped dormers and rounded turrets. Its pink granite walls were quarried in Maine and New Hampshire. The waiting room had a checkerboard floor of white marble and gray slate tiles and two fireplaces carved from red sandstone.

“It was such a beautiful building that it appealed to so many people,” Shettleworth said. “The clock tower was a symbol of a time when most people traveled by train, and the station was associated with many great events in their lives.”

The clock in the 138-foot-tall tower was reputed to be the most accurate outdoor timepiece in New England, Marcigliano said. It was equipped with a “double three-legged gravity escapement” device, invented by E.B. Denison for Big Ben at Westminster Abby. The clock face was saved from the demolition and is now in Congress Square.

A lot has changed since the station was razed. Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, establishing the National Register of Historic Places. Colleges and universities started offering degree programs in historic preservation in the late 1960s, said William Murtagh, an award-winning preservationist and former keeper of the national register who retired to Penobscot.

“As late as the 1950s, preservation was a genteel occupation of wealthy white women who established house museums,” Murtagh said. “People just weren’t aware of it. It wasn’t even a source of gainful employment because most house museums were run by volunteers. Today, preservation is part of the planning process.”

Today, the Maine Historic Preservation Commission shepherds a variety of federal and state preservation programs. Portland and other Maine communities have established historic districts where alterations to old buildings and construction of new buildings are reviewed and controlled to preserve the neighborhood character.

Portland has several historic districts, including the Old Port, the West End, the Eastern Promenade and, the newest, along Congress Street.

Challenges still facing the city include the need to preserve historic churches and meeting spaces that have dwindling memberships, said Bassett, head of Greater Portland Landmarks.

Her group is working to find compatible uses for old spaces, as VIA Agency recently did with the former Baxter Library at 619 Congress St. It also helps property owners maintain often-subtle architectural details that distinguish Portland from other cities.

“People have the perception that historic preservation has been a success and there’s not a lot more to do,” Bassett said. “We’ve made some really great progress over the years, but there’s still a lot more to do.”

Staff Writer Kelley Bouchard can be contacted at 791-6328 or at: kbouchard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.