KENNEBUNKPORT – Squinting against the afternoon sun, Bob Almeder looked from his porch toward the sand dunes and the beach below.

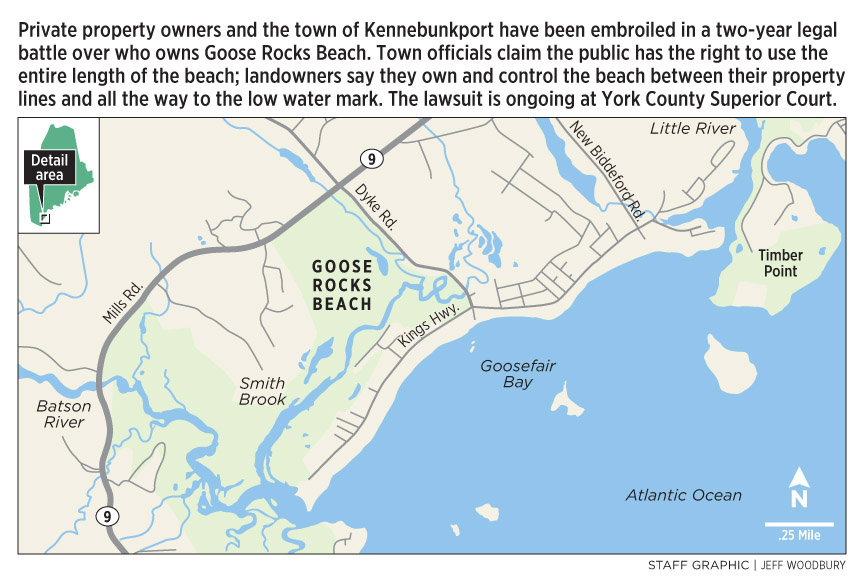

From Almeder’s property near the mouth of the Batson River, Goose Rocks Beach runs northeast for more than two scenic miles.

On Wednesday, the beach was a classic summer postcard. Families spread out on towels and blankets, the adults taking shade under umbrellas while kids tossed Frisbees. Plovers fed in tidal pools, then retreated to the dunes.

Nothing suggested that this narrow patch of sand has become ground zero in the latest battle for access to Maine’s beaches.

But that’s exactly what has happened.

“We all knew when we bought our properties that our deeds were down to the low-water line. All we were ever asking for was a declaratory judgment to show that we own the property,” said Almeder, a retired professor and one of 24 beachfront landowners who sued the town in the fall of 2009.

The lawsuit, he said, was a response to the town’s assertion that he and the other private owners had no enforceable right to limit public use of the beach in front of their homes.

“We have been demonized in all of this. I know of nobody who wants to stop anybody from walking the beach,” he said. “However, people are very zealous to keep their basic property rights.”

Town officials, with help from a grass-roots organization that has rallied support for public access, don’t see it that way.

The town claims that the beach has been public property since the 1680s, and that it has the Colonial-era documents to prove it. If that argument fails to persuade Justice G. Arthur Brennan in York County Superior Court, town officials also argue that the beach is public property because the public has earned a permanent recreational easement, by virtue of using the beach for centuries.

In court filings, the town attorney has said that when private property owners were granted beachfront land at Goose Rocks in the 1700s, those conveyances didn’t include the beach itself.

“One cannot own what was never given in the first place,” wrote Town Manager Larry Mead in a memorandum about the lawsuit in May.

Bound by the Batson River to the west and the Little River to the east, Goose Rocks Beach became a summer enclave in the late 1800s.

Simple cottages were built along King’s Highway — the narrow road that runs the length of the beach — and artists congregated at Sand Point on the east end.

The number of cottages gradually increased, and several side streets were built. In recent decades, many of the cottages were replaced or remodeled as year-round homes. Motels, condominiums and campgrounds off routes 1 and 9 increased the number of people recreating at the beach.

Kennebunkport residents have approved spending more than $600,000 in legal fees and document research to fight for public beach rights.

Both sides have submitted motions for summary judgment, but it could be years before the court case and a probable appeal from the losing side are resolved.

Outside of town officials, Mic Harris has been the leading voice for those who want to keep Goose Rocks open to unrestricted recreational use by the public. He created a nonprofit organization, Save-Our-Beaches.

Harris and his 10-member board of directors have waged a public information campaign through door-to-door canvassing, open neighborhood meetings, a website, www.save-our-beaches.org, and a Facebook page.

Signs and bumper stickers from Save-Our-Beaches can be seen throughout town.

“I want the family from Iowa who has never seen the ocean to be able to experience this with the same joy and awe as I do,” Harris said. “It’s a unique place that should be shared and not kept.”

Harris grew up in several beach towns in the South, married a third-generation Goose Rocks resident, and he moved in 1990 to a house a few blocks away from the beach. They purchased the home after the death of his wife’s grandfather, Bob Genthner.

“He helped build stairs coming down to the beach, and paths for the handicapped,” Harris said of Genthner.

“This community has always just enjoyed the beach together. Before all of this, there has never been any ‘private versus public,’” he said. Now, neighbors find themselves in a bitter legal dispute similar to the one endured many years ago by residents of the Moody Beach area in Wells.

That area was a quiet summer vacation spot until the 1970s, when demand for public beach access began to spill over from larger beaches. Some of the 100 or so beachfront cottage owners were dismayed by the crowds and their behavior.

“The property owners wanted the town to help them control the crowds, to cut down the drinking, partying and nudity,” said Bob Foley, a current Wells selectman. “They wanted a couple of lifeguards and a public restroom.”

The town declined, and in 1984 a group of owners sued the town, seeking a court decision that would force the town to enforce trespassing laws and restrict public use of the beach.

While the case was still pending, the Legislature in 1986 passed a law declaring that the public has a guaranteed right to use coastal lands between the high- and low-tide marks for recreation.

Later that year, though, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court ruled that the public does not have that right. The court said coastal ownership in Maine was governed by common law stemming from a 1647 Colonial ordinance. For land between the tides, the ordinance limited public access to “fishing, fowling and navigation.” Recreation, the court found, had not earned a spot on the list.

Over the next few years, the landowners at Moody Beach won their case, and the 1986 coastal land use law was struck down.

The state Supreme Court upheld the ruling by a 4-3 count in 1989.

More than two decades later, the landmark Moody Beach case continues to guide Maine’s coastal ownership disputes.

Interested parties along the coast are closely following the Goose Rocks case, to see if it might have a broader impact on Maine law.

They are also following a case that originated in Eastport, where a private property owner challenged a scuba diver for using his property to access Passamaquoddy Bay. The court heard oral arguments on the case last fall but has not yet issued a ruling.

Looking back on it, Foley, the Wells selectman, said it was unfortunate that the Moody Beach dispute ended up in court. The town has to bear the burden of the case’s legacy.

“It cost the town from a legal and financial standpoint, but also from a community standpoint,” Foley said. “The divisions are still there, and that’s very difficult.”

Staff Writer Trevor Maxwell can be contacted at 791-6451 or at:

tmaxwell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.