On a recent Friday, a day when temperatures would soar above 90 degrees across Maine, cars started to line up long before the gates opened at Scarborough Beach State Park.

By 9 a.m., the gleaming metal caravan stretched a half-mile north.

Later in the day, families sat in the line for an hour or more, waiting for parking spots to free up. For park manager Greg Wilfert, such long lines are not uncommon.

“I’ve been doing this a long time, and I don’t see the popularity going down. I see it going up,” said Wilfert, who has worked at the beach since 1972.

Last year, nearly 79,000 visitors entered the park, about 30,000 more than in 1999, when the current record-keeping system started. Collectively, the coastal state parks set an attendance record in 2010.

“Everyone wants to get to the beach, but there are only so many places you can go,” Wilfert said.

The battle for access, according to coastal resource experts, beachgoers and people who work at the beaches, is more intense than ever.

Maine boasts the longest tidal coastline in the nation, with 3,500 miles.

But only about 30 miles of that — less than 1 percent — is made up of publicly owned sand beaches. Privately owned beachfront makes up another fraction of the total, although state officials don’t have an estimate of that amount. The vast majority of the shoreline is rockbound.

By comparison, there are about 60 public beaches on the 560 miles of shoreline on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. One beach alone — the Cape Cod National Seashore — includes 40 miles of publicly owned sand beach.

Some privately owned Maine beaches, traditionally used by members of the public for generations, are becoming off-limits as coastal land is developed and as owners post signs to protect their property rights.

For those who seek out the beach for recreation, the rising costs and scarcity of parking, combined with a lack of public transportation to the beachfront, are other limiting factors.

And as the coast continues to be the focus of Maine’s population growth, there are more people who want beach access, from swimmers and surfers to kayakers, stand-up paddlers and dog walkers.

York and Cumberland counties, the southernmost counties that are home to the bulk of the public sand beach mileage in the state, gained more than 25,000 residents between 2000 and 2010, according to Census figures.

BIG DEMAND, LIMITED RESOURCE

“It’s a shame that you have to get here so early just to have a chance to park,” said Susan Ryberg of Falmouth.

On Wednesday, Ryberg sat in a beach chair at Scarborough Beach State Park, watching her 12-year-old son, Jack Sharp, surf. The weekdays, Ryberg said, are generally not as competitive at Scarborough Beach, which has room for about 270 cars and an overflow lot for another 140 across Black Point Road.

She said Jack would like to try surfing at Higgins Beach, just up Route 77 in Scarborough.

“We don’t go to Higgins at all because I don’t want to fight for parking,” Ryberg said.

Tourism, particularly from the Canadian province of Quebec, is another major component of the demand at Maine’s beaches, especially when the Canadian dollar is strong, as it is this summer.

Scott and Sue-Anne Rae, an architect and an educational consultant from Montreal, made their annual pilgrimage last week to York County.

They sat on the sand at Ogunquit Beach as their two daughters played nearby Wednesday afternoon.

“How can you not bring your kids to the ocean?” Scott Rae said. “It should be part of every childhood.”

For hundreds of yards in each direction, Ogunquit Beach was a bright mosaic of pinstriped umbrellas, chairs, flip-flops, radios and coolers. People streamed in from the dead-end street above, past motels and snack bars, where sea gulls plucked dropped french fries from the sidewalks.

The public lot closest to the beach, offering a daily rate of $25, was full, as were several other lots in the area.

Sue-Anne Rae is the third generation to vacation here. Her father bought a motel in Kennebunk around 1995 and sold it after 10 years. Maine’s beaches are so popular among residents of Montreal, the radio stations there broadcast weather forecasts for York County, she said.

“I remember walking the footbridge over there,” she said. “Back then we had plenty of room to spread out. It’s very different from when I was a kid.

“Just the cost of parking, it’s crazy,” she said.

WHO OWNS THE BEACH?

Another challenge is simply finding beaches that are publicly owned or otherwise open to the public. There is no comprehensive inventory, although one is in the works by the Maine Coastal Program, a division of the State Planning Office. Locals are known to keep quiet about smaller, lesser-known beach access spots.

Because of Maine’s unique coastal ownership law, the lines between public and private beach aren’t always clear.

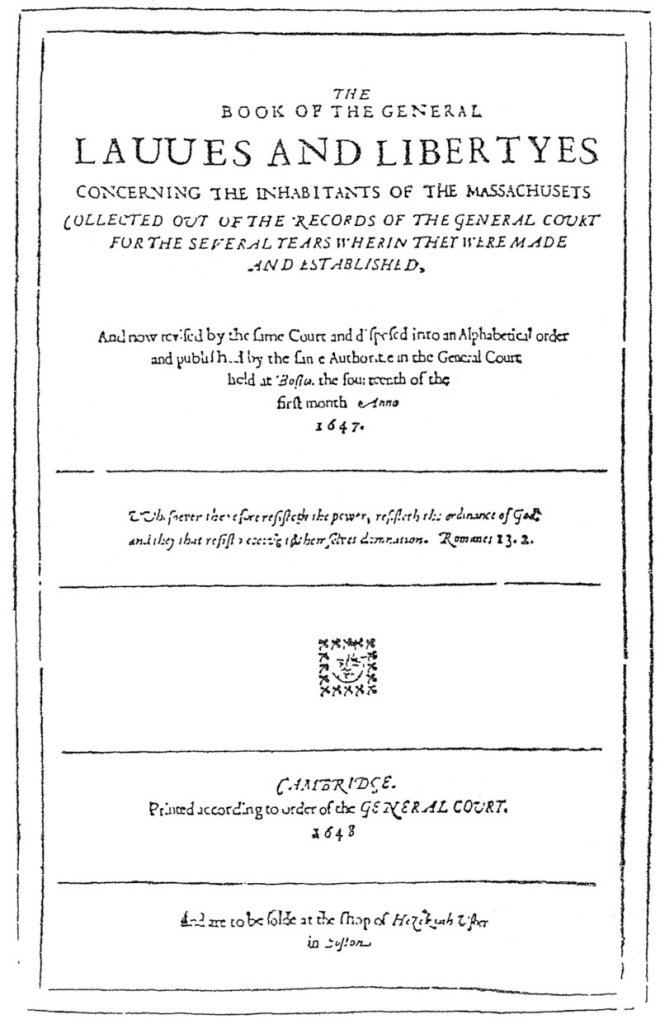

The common law dates back to a Colonial ordinance from the 1640s, when some lands north of the Piscataqua River were claimed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

In most coastal states — including California, Texas and Florida — beaches are considered as much a public resource as the ocean, and the state owns the area between low and high tide.

In Maine and Massachusetts, however, oceanfront owners generally own the shore all the way to the low-tide mark, including the beach, rocks and seaweed.

The public does have some limited rights to use private lands between the tides, but only for “fishing, fowling and navigation,” according to the Colonial-era ordinance.

The Moody Beach case, a landmark 4-3 decision by the Maine Supreme Judicial Court in 1989, held that the public does not have recreation rights on private tidelands.

That decision has been tested by several lawsuits, pitting oceanfront landowners against other residents and municipalities, over the question of who owns the beach. At least two such court actions, stemming from disputes in Kennebunkport and Eastport, are ongoing.

The beach law is one reason why the Surfrider Foundation’s “State of the Beach Report” ranks Maine dead last among all coastal states for public access.

Surfrider, a nonprofit organization based in San Clemente, Calif., claims to have over 50,000 members in 90 chapters worldwide, including roughly 150 members of Surfrider Maine.

“Lack of coastal access is a serious problem in Maine,” the Surfrider report says.

“The amount of private ownership along the coast and the fact that property owners may maintain ownership to the mean low-water mark makes this a difficult problem to address.”

Janice Parente of Scarborough, chair of Surfrider Maine, said the group has grown here since around 2000.

“We’re an organization that looks to preserve and retain existing access to the coastline. We also really want to promote the awareness of respecting and being stewards of the beach,” said Parente, a computer programmer who works in Portland.

Maine is getting a lot of attention from Surfrider’s national representatives, Parente said, in part because of the ongoing court battles over coastal ownership. Surfrider has intervened in the Eastport case, arguing that the state should update the Colonial-era ordinance to include public recreation on all intertidal lands.

“We strongly believe that the public has a right to recreate at the ocean,” Parente said. “We’re not in the 1600s anymore.”

The state Supreme Court heard arguments in that case last fall, but has not returned a decision.

TRADITIONS BREAK DOWN

The trend toward litigation is unfortunate, said Kristen Grant, who works for Maine Sea Grant and the Maine Cooperative Extension.

Part of her job is to help communities plan waterfronts to meet the needs of competing interest groups.

“A primary role for Sea Grant is to be a neutral convenor, to bring parties together and to help resolve controversies,” Grant said.

Historically in Maine, there has been a custom of “permissive trespass,” also known as “permissive access,” in which the public walks onto privately owned, unposted land to use a beach for swimming and sunbathing. The agreements were generally informal and unspoken, and any conflicts would be dealt with between the landowner and the specific users.

That dynamic started to break down during the coastal development boom in the 1990s, and the situation has not improved, Grant said.

As valuable coastal property changed hands, new owners built or improved homes and sometimes they brought different views on permissive access, she said.

Longtime owners who held onto their properties told Grant that public behavior started going downhill. Larger crowds were encroaching on beachfront homes, often leaving trash and dog waste.

“There used to be an understanding about the type of etiquette that was to be used. It was definitely an etiquette that coastal property owners will tell you is simply not being abided by today,” Grant said.

Seeing numerous court battles over beach rights, some oceanfront owners began posting their properties out of concern that they might get sued, Grant said. That often fueled animosity and distrust between the groups.

Sea Grant and several other agencies worked together to develop a website, Accessing the Maine Coast. Launched in early 2009, the site, www.accessingthemainecoast.com, sums up Maine’s coastal ownership law and provides information for various constituencies.

“Most users would say yes, beach access is becoming more difficult over the past 10 years,” she said. “The problems were already well on their way.

“There’s always hope that we can work together and find solutions,” Grant said.

“This is Maine,” she said. “We love to stay away from mandates and to work cooperatively if we can do it.”

Staff Writer Trevor Maxwell can be contacted at 791-6451 or at:

tmaxwell@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.