BAR HARBOR — Time stands still for 3,707,613 cryopreserved mice embryos at The Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor.

They lie chilled in steel tanks of liquid nitrogen to negative 196 degrees Celsius, at which temperature chemical reactions halt.

At some point, the embryos may be thawed and implanted in live mice to recreate valuable breeds of laboratory mice.

Mice are big business for Bar Harbor-based Jackson Lab. The 82-year-old nonprofit enterprise breeds and sells them to researchers worldwide, using the proceeds to help fund studies of the relationship between genes and human diseases.

But while mice are critical to Jackson Lab’s operations, executives attribute the organization’s longevity to its disease-fighting mission.

“The diseases we work on are the complex diseases of the developed world that so far have proved intractable,” said Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer Charles Hewett. “The hope that we offer (has) kept us here.”

Jackson Lab has a 43-acre campus in Bar Harbor and employs 1,212 people in the city, making it the largest workplace in Hancock County.

Jackson also employs roughly 110 staff at an office in Sacramento, Calif., and about 30 staff at other locations.

The average salary of Jackson Lab’s Bar Harbor employees is about $55,000 plus benefits, said Hewett.

Jackson Lab’s history can be traced to 1923, when University of Maine President Clarence Cook Little held a natural history camping trip with six students in Bar Harbor. In 1929, Little founded the Roscoe B. Jackson Memorial Laboratory, named after the president of Hudson Motor Car Co., who supported the new organization. Edsel Ford, son of Ford Motor Co. founder Henry Ford, was another backer.

Jackson Lab had seven staffers in 1930 and began selling mice in 1933. A fire in 1947 destroyed the organization’s facility and killed its mice.

In 1963, the organization became The Jackson Laboratory. New labs were build in Bar Harbor, but another fire in 1989 killed 500,000 mice.

Jackson has long been funded by significant government grants, many from the National Institutes of Health. In 2000, the agency granted Jackson $16.3 million for neurological disease research and $14 million to study heart, lung, blood and sleep disorders.

Another $15.1 million grant in 2006 allowed Jackson to create the Center for Genome Dynamics.

Jackson Lab opened a Sacramento, Calif., office in 2009. The so-called JAX-West office primarily sells mice to California-based biotechnology firms.

But mice sales declined during late 2008 and early 2009, and the organization faced a possible annual loss of up to $15 million.

Hewett said Jackson reacted by trimming the budget, which included laying off 55 staffers and eliminating 55 positions through attrition.

Jackson Lab’s operations broke even for the year ending in May 2009, though the organization lost millions in investments.

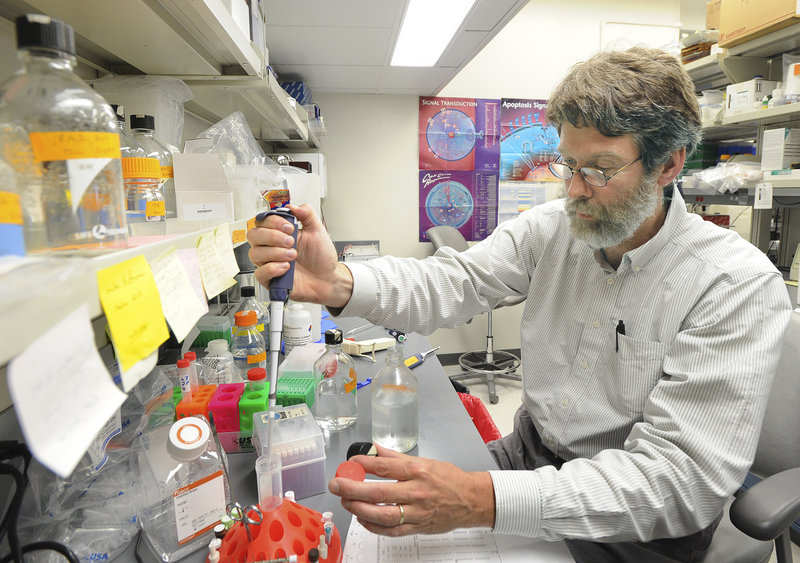

Today, scientists and professors in Jackson Lab’s 36 research programs study the role of genetics in metabolism, cardiovascular function, reproductive biology, birth defects, aging, deafness, obesity and a range of disorders. They also study cancer, HIV-AIDS, lupus, diabetes and other conditions.

Jackson Lab offers education and training programs for scientists and a summer intern program.

Jackson Lab’s last president and CEO, Richard Woychik, stepped down in January.

Chief executive duties are shared between Hewett and Robert Braun, associate director and chair of research, while the board searches for a permanent leader, said Jackson Lab spokeswoman Joyce Peterson.

The organization’s JAX Mice and Services division sells more than 5,000 varieties of laboratory mice and mice embryos to scientists and research institutions in 50 countries. There are some 1 million live mice at Jackson Lab in Bar Harbor.

Some mice are bred to come down with certain diseases.

Jackson Lab professor Derry Roopenian, for instance, works with mice that will get lupus. He and his staff look for early symptoms. “It’s far easier to treat before it become an incurable disease,” he said.

Jackson also breeds mice with custom genetic codes — genes that researchers, including those at pharmaceutical companies, think might cause diseases.

“You might have a theory about the genetic origins of a particular disease. We will make a mouse that has those genetic characteristics, and then see if that mouse exhibits those symptoms,” said Hewett.

Because maintaining colonies of live mice is expensive, Jackson Lab also cryogenically freezes mice embryos.

Thirty years from now, Jackson scientists can re-create the original colony by implanting the embryos in live mice, said Robert Taft, scientific director of reproductive science.

Taft said Jackson Lab also keeps mouse embryos as insurance: If a fire or other disaster kills live mice, the organization can replenish its stocks.

JAX Mice generated $98.7 million in revenue in fiscal year 2010, roughly 60 percent of Jackson Lab’s total operating revenue for the year, which was $166 million.

The nonprofit also received contributions and $54 million in government grants, many of them from the National Institutes of Health.

The organization had $200.1 million in unaudited operating revenue in fiscal year 2011.

Jackson Lab primarily studies mice genes, but Hewett said the organization’s future lies largely in human genetics.

He said scientists today can map a human’s genes in one day for $5,000 to $20,000. Ten years ago, it took 15 years and cost $3 billion.

As a result, scientists can compare healthy people’s genes to genes of those with conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, said Hewett.

That allows scientists to understand the genetic component of disease.

“We want to become closer to the human genome in research that we do,” said Hewett. “Historically, most of what we have done has used the mouse as a genetic model for the human being.”

Jackson Lab announced in 2009 a plan to open an institute in southwest Florida to advance human genetic studies. But earlier this year Jackson Lab cancelled the expansion after failing to land $100 million in state startup funding.

Hewett said Florida didn’t have the money or the political will to fund the project.

Jackson Lab also recently proposed to build a New York Genome Center in New York City with partners including Columbia University Medical Center, Rockefeller University, New York University, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

The city is expected to make a decision on the proposal by the end of 2011, according to a news release from the New York City Economic Development Corp.

Hewett said Jackson Lab will likely also hire human geneticists in Bar Harbor.

As a nonprofit group, Jackson Lab does not pay property taxes in Maine. However, the organization makes voluntary payments in lieu of taxes — so-called PILOT payments. In the last fiscal year, Jackson Lab paid $67,474, said Bar Harbor Town Manager Dana Reed.

Town Treasurer Stanley Harmon said Jackson Lab also pays more than $250,000 annually for water and sewage use and recycles waste produced by mice. He added that the organization provides steady, year-round employment in Bar Harbor, a tourist town.

Other organizations that don’t pay property taxes in Bar Harbor include nonprofit institutions like the College of the Atlantic, Mount Desert Island Hospital and Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory. And 43 percent of Bar Harbor’s land is part of Acadia National Park, said Harmon.

Some of Bar Harbor’s roughly 5,000 residents view the company’s mouse production division as a profit-making arm that should pay property taxes, said Ruth Eveland, chairwoman of the Bar Harbor Town Council.

“People perceive there is a factory aspect to it,” she said.

Eveland added that Jackson Lab probably takes the most political heat over its nonprofit status because it is the largest employer in the region.

Harmon said that if Jackson were a for-profit company it might pay about $2 million annually in property taxes.

But Hewett, the lab’s executive vice president, said Jackson Lab contributes most of the PILOT payments received by the town, and he said mice sales “make biomedical discovery possible in research labs around the world.”

“It is centric to our mission, and that’s why it’s a nonprofit activity,” he said.

Jonathan Hemmerdinger can be reached at 791-6316 or:

jhemmerdinger@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.