BOSTON — James “Whitey” Bulger’s capture could cause a world of trouble inside the FBI.

The ruthless Boston crime boss who spent 16 years on the lam is said to have boasted that he corrupted six FBI agents and more than 20 police officers. If he decides to talk, some of them could rue the day he was caught.

“They are holding their breath, wondering what he could say,” said Robert Fitzpatrick, the former second-in-command of the Boston FBI office.

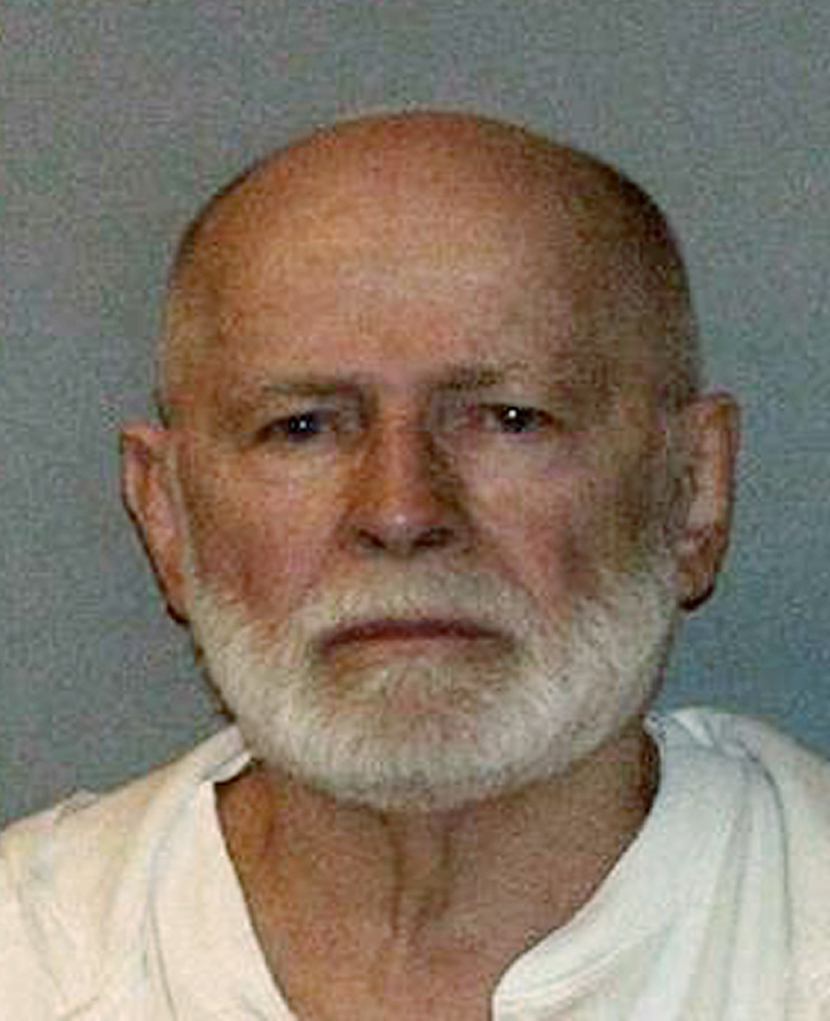

The 81-year-old gangster was captured Wednesday in Santa Monica, Calif., where he apparently had been living for most of the time he was a fugitive. He appeared this afternoon inside a heavily guarded federal courthouse in Boston to answer charges he committed 19 murders.

Bulger, wearing jeans and a white shirt under a white unbuttoned shirt, was brought into court in handcuffs, which were then removed. He looked tan and fit and walked with a slight hunch.

He had back-to-back hearings for two separate indictments. Attorney Peter Krupp was appointed to represent Bulger today, but Bulger asked that a public defender be appointed.

The government objected, citing the $800,000 found in his apartment and “family resources,” including money from immediate family members.

“We feel he has access to cash,” said prosecutor Brian Kelly.

In the second hearing, Magistrate Judge Marianne Bowler asked Bulger if he could pay for legal counsel.

“I could, if you give me my money,” Bulger replied.

The government is seeking to seize Bulger’s assets, which prosecutors said included the cash and 30 guns found in the apartment.

Prosecutors also asked that Bulger be held without bond. Bulger waived his right to a detention hearing today, but Krupp says he may ask for a hearing later.

Bulger’s girlfriend, who was arrested with him, was scheduled to appear in court on charges of harboring a fugitive.

Bulger, the former boss of the Winter Hill Gang, Boston’s Irish mob, embroiled the FBI in scandal once before, after he disappeared in 1995. It turned out that Bulger had been an FBI informant for decades, feeding the bureau information on the rival New England Mafia, and that he fled after a retired Boston FBI agent tipped him off that he was about to be indicted.

The retired agent, John Connolly Jr., was sent to prison for protecting Bulger. The FBI depicted Connolly as a rogue agent, but Bulger associates described more widespread corruption in testimony at Connolly’s trial and in lawsuits filed by the families of people allegedly killed by Bulger and his gang.

Kevin Weeks, Bulger’s right-hand man, said the crime lord stuffed envelopes with cash for law enforcement officers at holiday time. “He used to say that Christmas was for cops and kids,” Weeks testified.

After a series of hearings in the late 1990s, U.S. District Judge Mark Wolf found that more than a dozen FBI agents had broken the law or violated FBI regulations.

Among them was Connolly’s former supervisor, John Morris, who admitted he took about $7,000 in bribes and a case of expensive wine from Bulger and henchman Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi. Morris testified under a grant of immunity.

In addition, Richard Schneiderhan, a former Massachusetts state police lieutenant, was convicted of obstruction of justice and conspiracy for warning a Bulger associate that the FBI had wiretapped the phones of Bulger’s brothers, one of whom, William, was the powerful leader of the Massachusetts Senate for 17 years.

Edward J. MacKenzie Jr., a former drug dealer and enforcer for Bulger, predicted that Bulger will disclose new details about FBI corruption and how agents protected him for so long.

“Whitey was no fool. He knew he would get caught. I think he’ll have more fun pulling all those skeletons out of the closet,” MacKenzie said. “I think he’ll start talking and he’ll start taking people down.”

A spokesman for the Boston FBI did not return calls seeking comment. In the past, the agency has said that a new generation of agents has replaced most or all of the agents who worked in the Boston office while Bulger was an informant.

Some law enforcement officials said they doubt Bulger will try to cut a deal with prosecutors by exposing corruption, in part because he will almost certainly be asked to reveal what contact he had with his brothers while he was a fugitive and whether they helped him in any way.

“If Bulger talks, he would have to talk about his brothers, and I can’t see that happening, said retired state police Detective Lt. Bob Long, who investigated Bulger in the 1970s and ’80s. “They are not going to take selective information from him — it’s either full and complete cooperation or nothing.”

Criminal defense attorney and former Drug Enforcement Administration agent Raymond Mansolillo said Bulger may not have any incentive to talk. “The FBI may say, ‘You’re going to jail or you’re going to be killed. We’re not offering you anything,'” said Mansolillo, who once represented New England crime figure Luigi “Baby Shacks” Manocchio.

But retired Massachusetts state police Maj. Tom Duffy, one of the lead investigators in the Bulger case, said Bulger may agree to talk if he thinks it could help his girlfriend, Catherine Greig.

“It’s very possible he’s concerned about her well-being — she was with him for 16 years and was very loyal to him,” Duffy said. “That may be a bargaining chip for the government during negotiations.”

Security at the South Boston courthouse was tight for Bulger’s arrival. At least two Coast Guard boats, one state police vessel and a Boston patrol boat circled the harbor.

Among the onlookers was Margaret Chaberek, who grew up in Bulger’s home base of South Boston. “I’m here to see him get what he deserves,” she said.

Ina Corcoran of suburban Braintree came on her day off to witness a piece of history and sat on a bench outside the fifth-floor courtroom, saying it was like being there to see Al Capone.

“If you could go back in time to be in that courtroom, wouldn’t you?” she said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.