EAST BALDWIN — One evening about 35 years ago, Glenn Haines went for dinner at a neighbor’s house just across the way.

He remembers nothing about the meal, but hasn’t stopped talking about the house.

The narrow staircase and walls of upstairs bedrooms of the 1838 cape are decorated with elaborate and unusually detailed hand-painted folk-art illustrations. Floor-to-ceiling murals depicting quiet rural scenes adorn the walls, spinning a narrative that suggests an idyllic country life.

Birds sing in blossoming trees, schooners sail under the wisp of a perfect wind, and a hunter aims his rifle at plump prey.

“I didn’t know the artist or the history. I was just dumbfounded by the walls. We were mesmerized by those walls,” Haines said recently, still obsessed by the murals all these years later.

Haines and his wife, Norma, bought the house in the early 1980s and have served as its custodians since. This spring, they deeded the walls of the house to the Rufus Porter Museum of Bridgton. Conservators are removing the walls by cutting away entire sections of the plaster and lathe construction.

In all, they are trying to remove 17 complete wall units, some as large as 11 feet across and 7 feet tall.

Once removed, the walls – along with trim boards, a fireplace mantel, a stairway and all interior woodwork except the floorboards – will go into storage. Sometime next year, they will be reinstalled in the new Rufus Porter Museum, scheduled to open in a restored 1830s home on Main Street in downtown Bridgton.

The current museum operates in a small red building on the outskirts of town. The building and its contents will be moved to the new location next year as well.

A centerpiece of the new museum will be the walls from the East Baldwin home, reassembled to appear as they are now.

“We lived for those walls for 20 some-odd years,” Haines said. “At this point, to see them in a public domain, never to be sold and always available to be viewed – that is a goal of mine. This is what we always wanted to see happen.”

The walls are the handiwork of Jonathan D. Poor, Rufus Porter’s nephew. Porter was an artist and innovator who was born in Massachusetts but made his home in western Maine. He lived from 1792 to 1884. The museum preserves and celebrates his heritage.

Poor learned the mural trade from Porter, who painted wall murals and portraits for families across New England and beyond. For a period in the early 1820s, it is believed that Poor accompanied his uncle on trips through New England.

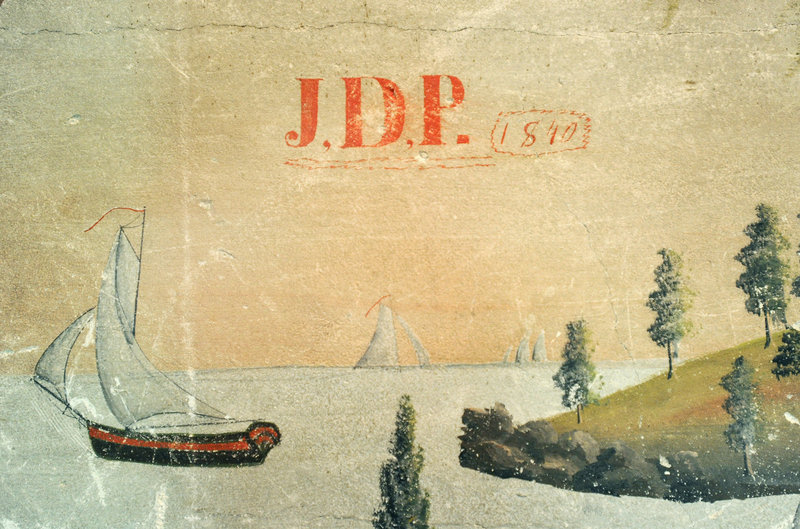

Poor signed the wall with his initials in bright red ink: “J,D,P. 1840.”

THE BEST OF JONATHAN POOR

These walls represent the very best of his work, said David Ottinger, a conservationist from Arlington, Mass., who is working with the museum on this project.

“A large strength of this grouping is how they work together,” he said. “The walls are integrated with the design and architecture of the house. We are delighted they are being preserved. These murals were common, but increasingly they are a vanishing resource. When I first saw this house, my feeling was, ‘These walls must be saved.’

“They are the highest example of Jonathan Poor walls. It would be a disaster if they were lost.”

Jane Radcliffe, a Porter scholar from Hallowell, said Porter influenced many young painters. The Porter school of landscape murals included many of the teacher’s disciples, and his nephew was among the best of them. Poor painted murals in many homes, and this gem in East Baldwin was one of his last.

Dr. James Norton of Standish moved to East Baldwin in 1834, and built this home in 1838. He settled with his wife and began a family. Poor painted the murals in 1840, when the house was still new. He lived in Sebago with his wife, who was ill at the time and died the same year that Poor painted the murals. Although it is entirely speculative, there is a theory that Poor treated these walls with greater attention in return for medical care for his wife from Norton.

The walls are still in very good shape, Ottinger said. The Norton family cared for the home until 1940, so it has had relatively few owners for its age. The walls were never varnished or painted over.

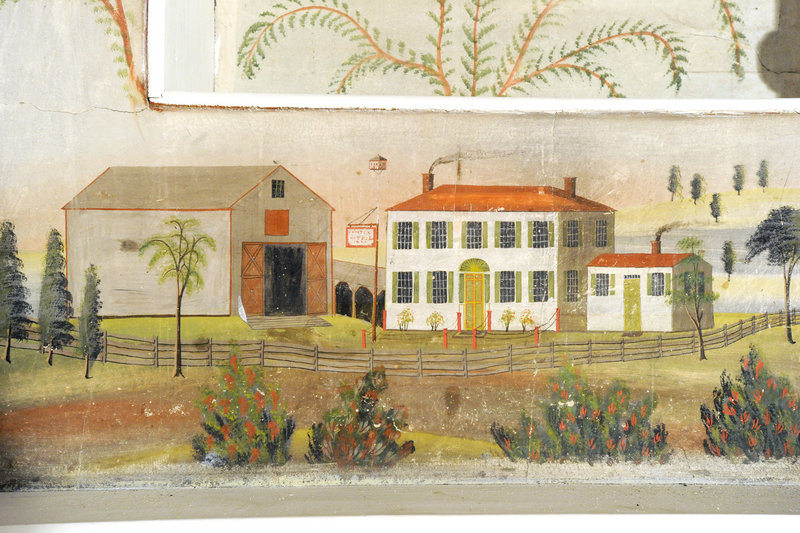

“What makes these murals unique is their depiction of an American scene,” Radcliffe said. “Other people did wall paintings before this, but they were European scenes. These scenes are what you would see when you looked out the window in 1840.”

Indeed, in one panel, Poor painted an elaborate farmhouse and barn with a sign in the front yard that says “J. Norton Hotel, 1840.” In another, a sailing vessel approaches an island that includes a lookout bearing some structural resemblance to the Portland Observatory.

There’s a certain iconography in these paintings that is meaningful locally. As Radcliffe noted, “It’s not just random trees and birds that he’s painting. This is true American art from the countryside.”

Saving the old plaster walls involves months of preparation.

Ottinger and his team began in the spring and worked from the outside in. To gain access, workers opened up exterior walls. To help hold the plaster, lathe and vertical studs together, volunteers applied a coat of rabbit glue to the back of the walls. The rabbit glue acts as an adhesive. Almost all the work is done by hand to avoid vibrations that might damage the brittle plaster.

After the old walls are removed and safely transported into storage, a crew will come in and rebuild the interior of the Norton house with modern building materials.

Haines and his wife then plan to put the house on the market without worrying what a future owner might do with the walls. The uncertainty over the long-term care of these walls motivated Haines to purchase the house in the first place.

“We never felt that we owned the house,” he said. “Certainly, we never owned the walls. We were custodians. I cannot express how strongly we feel about those walls. They feel like a part of us.”

Staff Writer Bob Keyes can be contacted at 791-6457 or at: bkeyes@pressherald.com

Follow him on Twitter at: twitter.com/pphbkeyes

Send questions/comments to the editors.